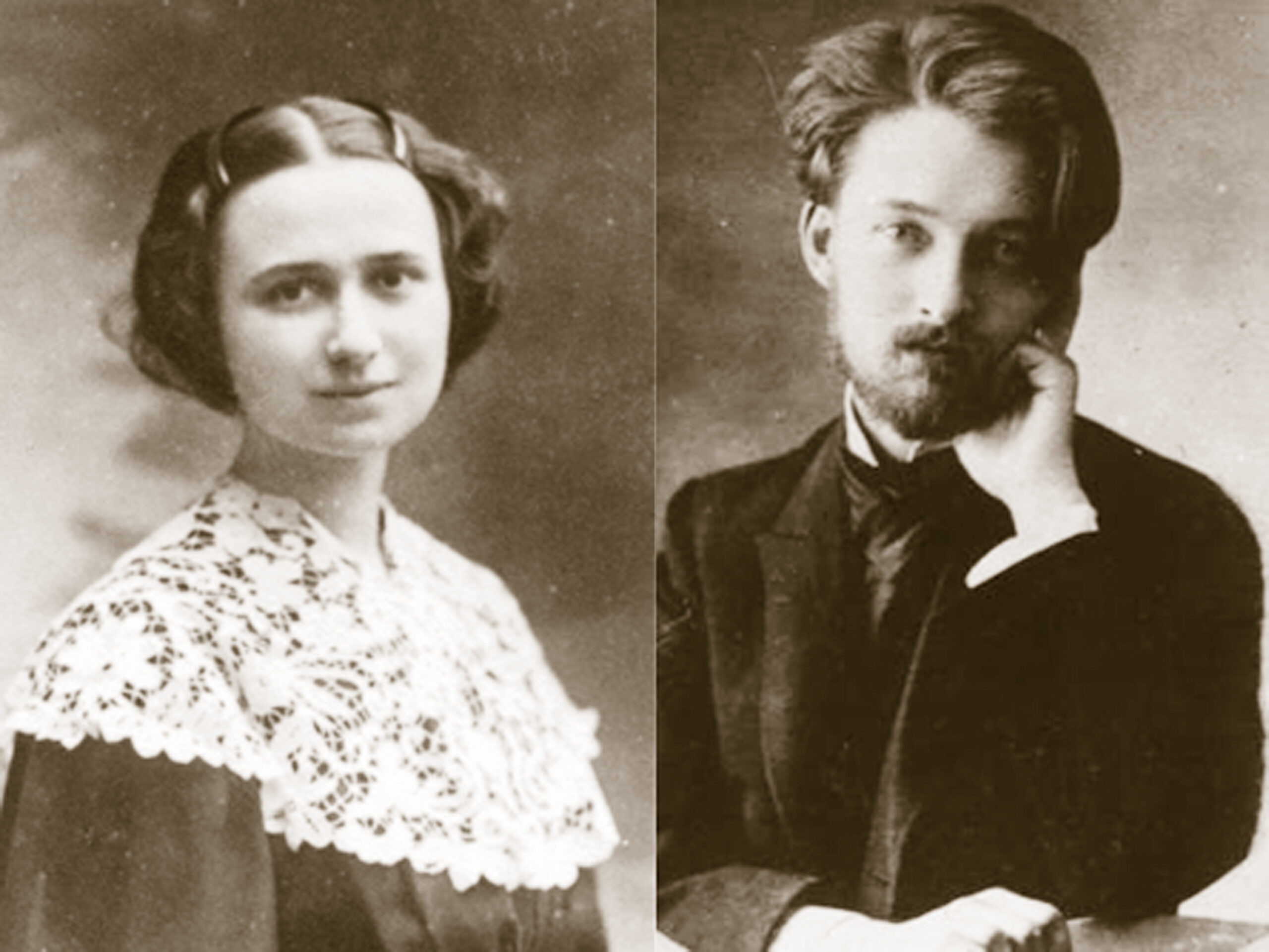

When the Russian young woman, Raissa Oumansov, began her studies at the University of Paris, she was seventeen years old and the year was 1900. It was a time of great scientific achievements and the Sorbonne was one of its centers. Marie and Pierre Curie, for example, had discovered radium there only two years before. It was natural, therefore, for Raissa to turn to the sciences for the answers she sought. To her dismay, however, she soon discovered that her professors were either strict materialists or simply did not pose for themselves questions concerning truth and meaning. Hope began to wane in her heart. Yet, she also continued to await “some great event, some perfect fulfillment.” The first step toward that fulfillment came when she met the man who would become her greatest companion during her earthly pilgrimage: Jacques Maritain. Almost from the moment that Jacques Maritain introduced himself to Raissa, they became inseparable. They were both students at the Sorbonne, he a year older than she, and they both were searching for the meaning of their lives. Jacques Maritain came from a family that embodied the values of the French Revolution. He discovered, however, what many others of his generation would one day recognize: the agnosticism that was their heritage was too thin a soil for the sense of justice that burned in their hearts. To withstand the winds of tyranny, justice needs deep roots and a rich soil in which to sink them. It was during his search for that rich ideal soil that Jacques encountered Raïssa. In the friendship that grew between them, they undertook the search together. In the midst of their distress, Jacques and Raissa reached a fateful decision that would shape the rest of their lives. While strolling through Paris, they both agreed that if it were impossible to know the truth, to distinguish good from evil, just from unjust, then life was not worth living. In such a case, it would be better to die young through suicide than to live an absurdity. They were spared from following through on this because, at the urging of their friend, Charles Péguy, they attended the lectures of Henri Bergson at the Collège de France. Bergson’s critique of scientism dissolved their intellectual despair and instilled in them “the sense of the Absolute.” Then, through the influence of Léon Bloy, they converted to the Roman Catholic faith in 1906. God, in His great mercy, led them to Christ, to baptism in the Catholic Church and to the consolation of the Eucharist. In reading Bloy’s great novel, The Woman Who Was Poor, the Maritains encountered the greatness of the Christian saints. “What struck us so forcibly on first reading Bloy’s novel was the stature of this believer’s soul, his burning zeal for justice, the beauty of a doctrine which, for the first time, rose up before our eyes,” they later confessed. Upon meeting Bloy and his family, they were even more impressed. His poverty, his faith, his heroic