News has recently surfaced that Pope Francis might visit East Timor later this year (as part of a proposed trip to the larger nations of Indonesia and Papua New Guinea). Though many people have never heard of this country, Timor-Leste–a nation of about 1.4 million people in the southeastern part of the Indonesian archipelago–is noteworthy for multiple reasons. Among these reasons is that, with a population that’s 98% Catholic, this nation has the world’s highest proportion of Catholics outside of Vatican City.

Timor-Leste, formerly known as East Timor, is also remarkable for the extent of hardship that so much of its population has endured. Tumult and trauma scorched this small land in the late 20th century, when as many as one-third of its people died due to violence, disease, or starvation.

Catholicism arrived here in the early 1500s by way of the Portuguese, who kept the territory as one of its colonies for more than four centuries (the Japanese briefly occupied the region during WWII). Portuguese remains an official language, along with Tetum (an Austronesian language). English and Indonesian are used to a lesser extent.

Independence

East Timor became an independent country on November 28, 1975. And then, nine days later, it was invaded by Indonesia. Thus began decades of conflict between pro-independence East Timorese militias and the Indonesian military. Additionally, many non-combatants, including women and children, died violently in the streets or were arrested and “disappeared.”

When the carnage began, only 20% of East Timorese were Catholic. However, amid the prolonged violence, many non-Catholics began to turn to Catholic churches as places of physical, and eventually spiritual, refuge. Also, many Catholic clergy were outspoken against human rights abuses (some even offered direct assistance to pro-independence fighters).

At the forefront of clergy supporting the East Timorese was Bishop Carlos Ximenes Belo, whose bravery and moral authority saw him win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1996, an award he shared with José Ramos-Horta, who has served at different times as the country’s president and prime minister.

Aside from the native-born Bishop Belo, other Catholic heroes include Pope John Paul II, who brought international attention to the East Timorese struggle when he visited the capital city of Dili in October 1989. Tension was so high during this visit that violence erupted between chair-throwing East Timorese demonstrators and club-wielding Indonesian police while the pontiff was holding an outdoor Mass.

This skirmish would prove mild compared to what took place on November 12, 1991, when some 250 unarmed civilians were gunned down by Indonesian security forces during a funeral procession at Dili’s Santa Cruz cemetery.

“In Cold Blood”

A foreign camera crew managed to capture video footage of the slaughter. This footage, successfully smuggled out of East Timor, was later featured in the documentary In Cold Blood: The Massacre of East Timor, which helped garner international outrage at a military occupation that many would come to regard as genocide.

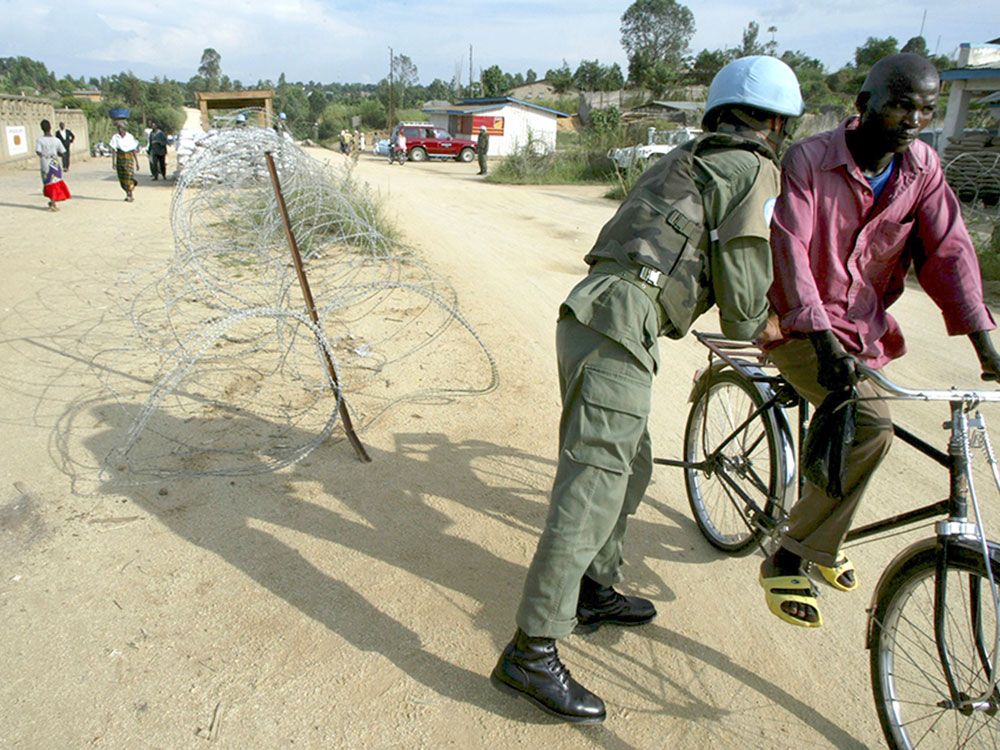

A UN-supervised August 1999 referendum on independence saw about 80% of East Timorese voters express their wish to separate from Indonesia. Immediately after this landmark vote, anti-independence Timorese fighters, backed by Indonesia, went on the counteroffensive. Within a few weeks, they had slaughtered about 1,400 persons (including priests and nuns), turned many more into refugees, set fire to entire villages, and all but decimated the county’s already-meager infrastructure, including its schools.

Such destruction of schools undoubtedly increased the number of East Timorese (some estimate almost half of the population) who have never received any formal education whatsoever.

Rates of illiteracy, though improving in recent years, are still very high by 21st century standards. This is particularly so among women, with some estimates saying that more than half of them remain illiterate. And most of the population, male or female, has never read a newspaper.

About two-thirds of the nation lives in small, geographically isolated villages. Half of the nation lives in extreme poverty (less than $1.90 USD per day), and half of all children under age 5 suffer from malnutrition.

Timor-Leste continues to have much difficulty creating jobs for its younger citizens. Many of the young men, particularly in urban areas, have gravitated towards a gang lifestyle and crime.

Though this phenomenon has brought lawlessness to the streets, Timor-Leste–since beginning its hard-earned independence on May 20, 2002–has seen nothing approaching the degree of mayhem that occurred in the late-20th century.

Robust Faith

Despite all the hardship, this country has maintained a robust faith. Instead of seminaries closing due to lack of enrollment, Timor-Leste has contended with the opposite problem of hundreds of aspiring seminarians turned away due to lack of openings.

A papal visit could bring some deserved attention to this young, underdeveloped country still seeking to recover from recent carnage. Such a visit would also enable the pope to spend time in a country that’s almost as Catholic as the one in which he reigns. Published in Aleteia