Talal Darwish has the smile of a happy man. The worst of a two-year journey to escape a bloody war in Syria ended last March when his family arrived in the Portuguese town of Nazaré from Greece. “We are finally safe,” he said.

The big waves of this seaside resort, 100 km north of Lisbon, made famous by American surfer Robert McNamara, might evoke images of migrants crossing the stormy Mediterranean. It is only but a resemblance. Nazaré is now a paradise for Talal, his wife Mushira and their seven children after a long ordeal.

They reached Portugal under a European Union relocation and resettling program of 160,000 asylum seekers stranded in Greece and Italy. The Portuguese government offered to host 10,000 refugees, more than double its 4,486 quota.

The Darwishes are guests of Confraria de Nossa Senhora da Nazaré (Guild of Our Lady of Nazareth), a Catholic institution that is doing the utmost to provide the family with all they need.

Lodged in the local community center until mid-June, they have now moved to a private house. It is a spacious building in the touristic old village of Sítio that was totally restored and furnished to accommodate them.

The road to exile began in 2014. They left the city of Hama, located 200 km north of Damascus that has been, for decades, a resistance symbol to the Syrian regime.

“I remember the 1982 massacre,” says 42-year old Talal, sitting next to his wife, three sons and four daughters in one of the community center’s living rooms.

“I was a kid but everybody talked about it. The city was completely razed to the ground and, later, rebuilt as a message to the Muslim Brotherhood.”

At least 25,000 people were killed in Hama in 1982 after several opposition attempts to oust and kill President Hafez al-Assad. His son and successor, Bashar al-Assad, brought the war back in 2011 when he violently repressed peaceful demonstrators demanding political reforms.

Since then, Syria is engulfed in an all-out armed conflict, entangling internal and external forces. The country is totally destroyed. A new regional map has been drawn.

At least 13.5 million Syrians need humanitarian assistance; 4.8 million are refugees and 6.5 million are internally displaced. Half of those affected are children.

Life-saving

“I was a farmer,” says Talal, his words translated from Arabic by Ben Salem Khalifa, a Tunisian businessman who settled in Nazaré and volunteered to assist his new friend.

“We had a normal life until it became unbearable. It was impossible to live under constant aerial strikes, bombs and bullets. Innocent people were being arrested at their homes and schools. The streets were full of bodies. For two years we ran from one place to another looking for shelter. One day, I said enough is enough.”

They left with minimal belongings – the clothes they were wearing, a few carpets, pillows, some cash and a cellphone. “Only our lives mattered.”

It took them four days to reach the border with Turkey. Here, they shared a house with 20 other people. Until 2016, Talal, his 32-year old wife Mushira and their eldest son, 13-year-old Saddam, worked in olive archards. They saved money for a bigger dream.

After two more kids were born in the neighboring country, the Darwish family tried to enter Europe. “We paid $4,000 dollars to a smuggler to take us to Greece,” recalls Talal.

“It was a wild ride on several rubber dinghies, each one carrying 70 to 80 passengers. The sea was very rough. At least three people disappeared. We were rescued by the coast guard before reaching the shore.”

They were fortunate. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), more than 3,770 migrants and refugees were reported to have died trying to cross the Mediterranean in 2015. Of those, more than 800 died in the Aegean, crossing from Turkey to Greece.

The Darwishes planned to join other relatives in Germany but accepted to be transferred to Portugal.

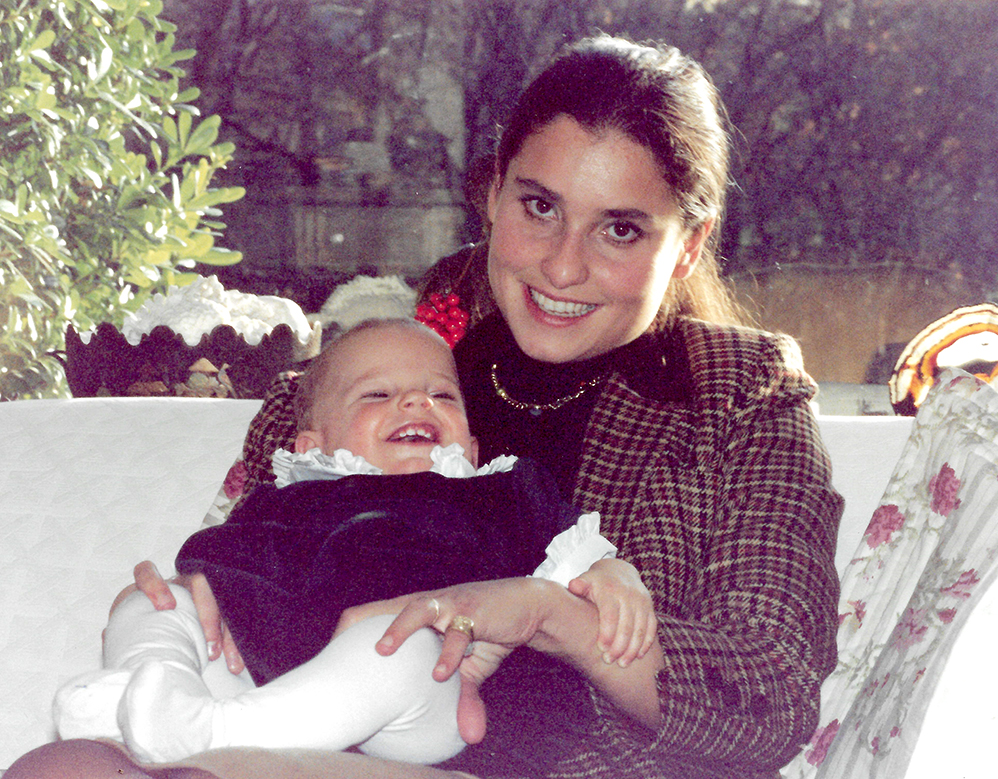

“We are grateful,” says Mushira, gently embracing her 4-month old baby Fatima, while calming down three other daughters – 5-year-old Raghad, 3-year-old Shahad, and 2-yea- old Rimas – demanding her attention.

“We will stay in Portugal until the war ends. Afterwards we will return to Syria.”

A sanctuary

Confraria da Nazaré decided to register as one of the host institutions of the Refugee Support Platform (PAR) in September 2015, after Pope Francis called on “every parish, religious community, monastery and sanctuary” to take in one refugee family.

“Tens of thousands of refugees, fleeing death in conflict, are on a journey of hope,” the Pontiff said in front of a crowd in St. Peter’s Square in Rome. “The Gospel calls us to be close to the smallest and to those who have been abandoned.”

In April, the Bishop of Rome put his words into action. After a visit to the Greek island of Lesbos, he took on his plane three families of refugees from Syria. The 12 people, six of them children, were housed by the Saint Egidio religious community in Rome.

Those families had been chosen out of some 3,000 people at a detention camp “simply because their paperwork was sufficiently in order to conclude a rapid agreement on their transfer with the Greek and Italian governments,” Francis told reporters. “I didn’t make a choice between Christians and Muslims. All refugees are children of God.”

Susana Zarro, public relations officer at Confraria da Nazaré, remembers the day she received a call from the Jesuit Refugee Service to pick up the Darwishes. They arrived at a military airport in Lisbon together with 60 other refugees. “When I saw them, looking so fragile, I said to myself: ‘I hope that you will come with us to Nazaré.’ And so it was.”

Everything was ready to welcome the guests: a large room with five colorful beds, packed with toys and clothes, bicycles and some books, a white satin double bedroom with a baby crib, a sizeable kitchen where Mushira displays her cooking skills.

As part of the integration’s process, the family immediately entered Portuguese language classes. Mushira is rather fluent by now, able to easily communicate with Susana and the journalists visiting the center.

Saddam and his brothers Ali (8-year -old) and Khaled (10-year-old) spend the days in the primary school, the younger sisters in the kindergarten. Talal is registered with the employment center.

The family is united in grief and joy. Children listen attentively to what their parents say, obeying every order. When Ali tries to break his Ramadan’s fast, after a day at the beach with school colleagues with no food restrictions, Talal tenderly encourages the son to be brave. They are survivors after all.

Ben Khalifa, the Tunisian translator, is helping his new Syrian friends to fulfill their religious obligations. “Every Friday I drive them to a nearby mosque,” proudly said the pious Muslim whose late wife was Catholic.

At 5p.m., Talal’s cellphone interrupts our conversation. A muezzin calls for the third afternoon prayer. It was Ben who helped install the musical app.

New citizens

For Europe, the arrival of thousands of refugees is a challenge but could also be a game changer. They will “create more jobs, increase demand for services and products, and fill gaps in European workforces—while their wages will help fund dwindling pension pots and public finances,” according to an investigation quoted by The Guardian.

This report, “Refugees Work: A Humanitarian Investment That Yields Economic Dividends,” was released by the Tent Foundation, a non-government organization, and the Open Political Economy Network, a new think tank.

“The main misconception is that refugees are a burden but that’s incorrect,” said one of the authors of the report, Philippe Legrain, former economic adviser to the president of the European Commission.

“To put it simply, refugees who take jobs also create them. When they spend their wages, they boost demand for the people who produce the goods and services they consume.”

Refugees could solve a huge demographic problem in Europe as well. “By 2030, the working-age population is projected to shrink by a sixth (8.7 million people), while the old-age population will grow by more than a quarter (4.7 million),” writes Legrain. As such, “an influx of younger refugees could help care and pay for the increasing population of pensioners.”

In Nazaré, the Darwish family is ready for a solid commitment. Talal used to drive a tractor in Turkey. Mushira cooked for more than 70 people. “We will accept whichever jobs we will get,” she says. “We just want to be close to our children.”

If they were looking for a miraculous place, they have found it. They live on the top of a cliff where, according to a legend, on the foggy morning of September 14, 1182, a man called Dom Fuas Roupinho was rescued by divine intervention.

He found himself on the edge of a rocky point suspended over the sea while chasing a deer. When he realized the danger that he was facing, he prayed to an image of Our Lady with the Infant in a small grotto nearby.

“His horse suddenly stopped, saving the rider and his mount from a drop of more than 100 meters that would certainly have caused their death.”

The Darwish’s new house is close to the Chapel of Memory that Fuas Roupinho ordered to be built over the grotto and to the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Nazaré, where the image of the Black Madonna, breastfeeding Baby Jesus is venerated by devout pilgrims.

The end of one journey marks the beginning of another.