The life of Leonard Cheshire followed a classic pattern of Christian hagiography: birth into a well-to-do family; a dashing, turbulent and spiritually thoughtless youth; an unexpected encounter with God, followed by conversion, suffering, voluntary poverty and dedication to prayer and good works. To describe holiness convincingly is quite difficult, but for Leonard Cheshire and his wife Sue Ryder there is no other word that accounts for their exceptional dedication to the most unfortunate, inspired by their Catholic faith. Especially Leonard, a modest, reserved but totally self-assured Englishman, who deserved to be called by Nehru, the father of independent India, “the greatest man since Gandhi.”

Leonard Cheshire was born at Chester, England, on September 7, 1917. His background was cultivated and secure. His father was professor of law at Oxford; his mother came from a military family. Anglicanism was in their blood but not taken very seriously. The family was close, affectionate and supportive. Young Leonard went to Oxford where he took a second-class degree in law and acquired a reputation for dare-devil exploits, disregard for authority and a self-assurance bordering on arrogance. He joined the University Air Squadron, learned to fly and found that he enjoyed it.

In early 1939, with war clearly looming, he applied for a permanent commission in the RAF (Royal Air Force). When war broke out, between June 1940 and August 1941, he carried out more than 100 bombing missions, encountering hazards and deaths on an almost unimaginable scale. In March 1943, he became the youngest group captain in the Service and in September that year was given command of the celebrated “Dambuster” squadron which specialized in low-level bombing. Cheshire was nearing the end of his fourth tour of duty in July 1944, when he was awarded the “Victoria Cross,” the highest British war decoration.

His citation read: “In four years of fighting against the bitterest opposition, he maintained a standard of outstanding personal achievement, his successful operations being the result of careful planning, brilliant execution and supreme contempt for danger. Cheshire displayed the courage and determination of an exceptional leader.”

Following a staff job in India, he was nominated by Churchill in 1945 to be one of the two British observers at the dropping of the atomic bomb on Nagasaki. This experience affected him deeply and convinced him that no government could ever again face the risk of nuclear attack, and that nuclear deterrence, therefore, opened up the possibility of world peace. To the end of his life, he believed in world peace as an attainable goal and nuclear deterrence as a necessary condition of achieving it. On his return from the mission, he left the RAF and went home to his house: Le Court in Hampshire.

The peacetime hero

The end of the war found him with no clear idea of what to do next. But the business of war, the horrors he had undergone and helped to inflict, the comradeship and discovery of his own gift for leadership had matured and deepened him. Cheshire had no religious feelings during the war. His conversion to Catholicism came later, starting in the unlikely setting of a Mayfair bar. A woman told him in the course of a conversation there that God was a real person, and, he said, “There wasn’t exactly a blinding light, but I suddenly knew she was right.” He began to pray…

In 1948, he heard that an acquaintance, Arthur Dykes, was terminally ill. Dykes asked Cheshire for a bit of land on which to park his caravan until he was on his feet again; it was apparent that nobody had told him that he was dying. Cheshire couldn’t maintain the deception and told Dykes the truth. To Cheshire’s astonishment, Dykes was much relieved. “Thank you, Len, for letting me know,” he said, “It’s not knowing that is the worst of all.” Cheshire invited Arthur Dykes to stay with him in his house.

Dykes was a lapsed Catholic, and asked for a priest. Cheshire’s conversations with Dykes and his encounter with the priest led to his characteristically sudden and decisive conversion to Catholicism. As Cheshire cared for Dykes, he learned basic nursing and became a frequent helper at the local hospital. Then someone brought along his elderly wife who was ill and bedridden, and Cheshire nursed her also, bathing her and caring for her needs.

Meanwhile, other broken or ailing people followed Dykes into Cheshire’s care, and before long he was running the first embryonic Cheshire home. He had found his vocation. He would recount this as if it were the most natural thing in the world for a man who had recently been the youngest group captain in the RAF to do. “I didn’t go looking for those people. They were on my path,” he explained. By the time Arthur Dykes died in 1948, there were 24 people staying at Le Court: there was no going back.

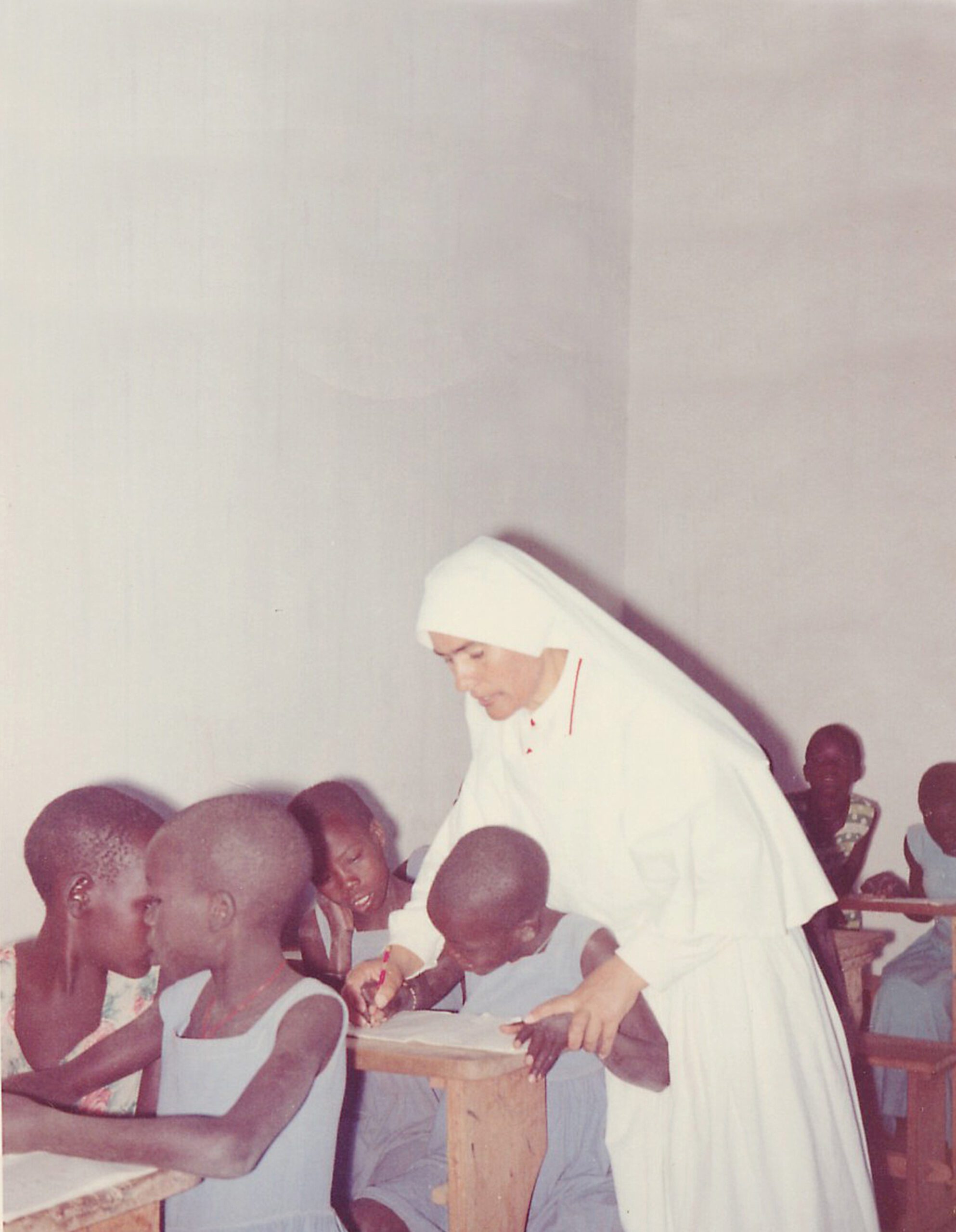

There followed the gradually accelerating spread of Cheshire Homes across the country, initiated by Cheshire himself and gaining momentum from his example and his genius for attracting and motivating willing helpers. At first, the homes were in effect hospices; but it gradually became clear that the focus should be on physical and mental disability. In 1951, Cheshire turned his attention to India and the first oversea home was started in Bombay where it still flourishes. By the time of his death in 1992, his foundation had become probably the largest disability care charity in the world, responsible today for 140 homes and services in the United Kingdom and supporting 240 more in 50 other countries, from Argentina to Indonesia.

There was nothing simple about this achievement. It is all rather extraordinary, owning to the attraction of Cheshire’s personality and his exceptional commitment. It is due to his determination, his courage, his charm tempered with occasional ruthlessness, his personal relationships with others (not least his devoted and exceptional wife, Sue Ryder) and his interior life as a Christian and a Catholic. Cheshire embraced Catholicism with the enthusiasm of the convert and with the single-mindedness which had characterized him in war.

The power of two

In 1952, Leonard fell seriously sick with tuberculosis, underwent the removal of one lung and spent two years in a sanatorium. This was a time of suffering, but also of intensified prayer and theological studies. When he came out, he was attracted by monastic life and almost resolved to join the Cistercians, “partly,” as he explained afterwards, “because they are absolute in their standpoint, and partly because I liked very much their balance of life, with the harmony between mental life, prayer and very hard physical work.” In the end, he opted for life in the world. He made no secret of his faith, and his lifestyle was as frugal as his travels and social obligations allowed. He embraced the world in the spirit of the cloister. And then love appeared.

Baroness Sue Ryder, a wartime member of the Special Operations Executive, was six years younger than Leonard, having been born in 1923. After the war, she had become famous for her work in Poland with concentration camp survivors. The “Sue Ryder Foundation” was established in 1953 to help the homeless in the aftermath of the Second World War but it subsequently widened its appeal to include the sick and needy in Britain and had a string of health care homes and 500 charity shops. Lady Ryder was a tireless worker for the disadvantaged, animated as she was by her deep Catholic faith. She was a hands-on charity director, often driving lorries of food and clothing to Warsaw to help the needy, especially while the country was under Communist rule.

When Cheshire first met Sue Ryder with the idea that they might work together, he had no thought of marrying, and neither did she. But a strong attraction grew up quickly. On April 5, 1959, in Mumbai’s Catholic Cathedral, he bound his life to hers. The marriage was a happy one, and they went to live in a Sue Ryder home in Cavendish, Suffolk. They were blessed with a son Jeremy and a daughter Elizabeth. In the 33 years of their life together, they continued their commitment to their different organizations.

In 1984, on the occasion of their Silver Jubilee, they were granted an audience by Pope John Paul II. In 1991 Leonard was given a life peerage. He lived through his final illness (Motor Neurone Disease) with exemplary spiritual fortitude. Queen Elizabeth II paid personal tribute to him in her Christmas message to the Commonwealth in December 1992. On the death of her husband, Sue Ryder became president of the Cheshire Foundation, which now runs over 200 facilities in over 50 countries, in addition to her role as leader of her own charity “The Sue Ryder Foundation.” Baroness Ryder died in November 2000, aged 77.

A paradox of love

Leonard Cheshire led two separate careers one after the other: he was a pilot and then a charity worker. Each one of them would have made him one of the most remarkable men of our time. He was one of the few people in the world to see a nuclear device dropped in anger, yet his name is primarily associated with conflict resolution and charitable work. There cannot be many men who have received their country’s highest award for wartime bravery, but who are remembered primarily for humanitarian service.

Cheshire had a slim athletic frame with heavy eyebrows and a ready smile that showed his two front teeth, and something of the clean-cut, boyish good looks. He was soft-spoken but could command respect and an extraordinary degree of admiration. It would be misleading to say he was modest. He was not diffident, and he would talk about his accomplishments, but he talked about them as if they were something anyone might do. He would answer questions about anything: his wartime feats, his feelings about facing death in the air, his courtship with Sue Ryder, his religious faith. Yet paradoxically, he left the impression of a man different from the rest of the people in many deep ways. Casual acquaintances could appreciate his courtesy, his evident seriousness of purpose joined with a sense of humor, without being aware of the extent to which his private life was centered on prayer.

His loyalty to the Church was unshaken by the upheavals which followed the Second Vatican Council and retained its initial whole-hearted simplicity: he had no time for religious controversy. In the weeks leading up to his painful death, he used to say: “All that matters to me is the Mass because it was at the Last Supper that we all became members of the Lord’s mystical body.” He confessed that he prayed constantly, saying a little prayer each time he answered the telephone, for instance. “It’s a matter of being in touch with God, and trying to find his purpose.” And perhaps this was the unfathomable aspect of Leonard Cheshire, the dimension the rest of the people could not see: whatever he was doing, he was trying to do it in the company of God.

Behind the apparent simplicity of Leonard Cheshire’s style lay the intellectual strength and depth of a man, who, as Cardinal Hume said at his Requiem, had given himself to God “in a manner that was total and even radical.” There were many who loved him, and many who would echo the words of the famous actor, Alec Guinness: “Leonard’s modesty, simplicity and sheer ordinariness were awe-inspiring… I always felt better for having encountered him.” As for his wife, at Sue Ryder’s death, somebody exclaimed: “It is an incredible loss! The news of her death has come as a terrible blow to many hundreds of thousands of people who knew, loved and admired Lady Ryder.” Their remarkable life was a paradox of love.