The God of the Bible is one who enters into communication with human beings and speaks to them. In different ways, the Bible describes the initiative taken by God to communicate with humanity in choosing the people of Israel. God makes His word heard either directly or through a spokesperson, like Abraham or Moses. God manifests Himself in the Old Testament as the One who speaks, saying who He is and who He is not.

The first idea is that God is one: “Listen, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord” (Deuteronomy 6:4).The uniqueness of God is expressed by the contrast between the living God and the dead nature of the other gods as seen in the strong polemic against idolatry (Psalm 115).

The second idea is that God is good: He rejoices at the goodness of His creatures. “And God saw that it was good” (Genesis 1). He especially wants us to be good. “I am the Lord, your God…You shall not kill” (Exodus 20).

Third, the God of the Bible is a personal God who wants to communicate with His creatures, with humanity and how He cares for us. God’s personality and concern for us is witnessed throughout the whole Bible in what we call Salvation History. Even in the beginning, God already says to Abraham: “I will bless you… and by you all the families of the earth shall bless themselves” (Genesis 12:1-5). And to Moses: “I am the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob” (Exodus 3: 6).

God cares for humanity, for His chosen people: “I have seen the affliction of my people…and I have come down to deliver them” (Exodus 3:7-8). God wants to have a covenant with His chosen people (Abraham); He gives them His Law, the content of the covenant, and wants them to understand that the heart of God’s covenant is love (Psalm 23, Psalm 103).

A God to love: from the Jewish confession of faith, the “Shema, Israel” in Deuteronomy, 6:4-5: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might”, to the countless expressions of love for God in the Psalms. This shows the originality and uniqueness of the Jewish understanding of God that has passed integrally in the New Testament. No servilism, no magic, but loving obedience, a mature relationship in a worship that enhances our human dignity.

God is a mystery

This is the itinerary of transcendence and it is the most remarkable albeit less known of God’s aspects. God is a great mystery: we cannot see God’s glory or His face, but only His back (Exodus 33:18-33). To see God’s face (or to hear His voice) is to die. This is why people are expected to cover their head when they pray.

The mystery of God is underscored by the prohibition to pronounce the name of God. God reveals His name to Moses, in the episode of the burning bush (Exodus 3:15) – Yahweh. One translation is “I am what I am”, meaning, that God doesn’t want to reveal His name as He is ineffable, transcendent.

The prohibition of the images of God is also stressing the mystery of God and helping the people to avoid idolatry: to worship the creatures instead of the Creator. The prohibition of making images is strong even nowadays in Judaism and Islam. It is a safeguard for monotheism.

This aspect becomes characteristically pathetic with the experience of the exile. The Jewish people are taken into captivity, they live among the pagans. As in the famous Psalm 137 “By the rivers of Babylon”, they are invited to sing the song of Zion, in the same way they are challenged by their enemies to show their God.

The author of Psalm 42 pours out his painful nostalgia for the temple of the Lord in poetic images: “Like the deer that longs for running streams, so my soul longs for you, my God. My soul thirsts for God, the God of life; when shall I go to see the face of God? I have no food but tears, day and night; and all day long men say to me: ‘Where is your God’?”

Jesus Christ

In the New Testament, we have the fact of the Incarnation. “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us and we saw His glory” (John 1:14). This is without doubt the most important line of the Christian Bible. The fundamental experience of the Apostles is the experience of Jesus, the incarnate Word, an experience of Jesus that is based on the senses as proclaimed by Saint John:

“That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our own eyes, which we have looked upon and touched with our hands concerning the word of life… we proclaim also to you, so that you may have fellowship with us” (1 John 1:1-4).

It shows the awareness of the unique charism or gift of the Twelve: the gift of the experience of Jesus which they had by being with Him from the beginning, throughout His life and especially the extraordinary experience of Jesus’ Resurrection. They are the eyewitnesses, the first hand testifiers of the reality of the blessed humanity of Jesus, “God with us”.

The experience of the senses, however, must lead to the leap of faith. This is the lesson of the episode of the doubting Thomas. His demands of putting his finger on the wounds of Jesus is legitimate. Jesus Himself, in the parallel passage in Luke, exhorts the disciples to touch Him. So He yields to Thomas’ demand, but He challenges him to go beyond the senses to a leap of faith.

It is as if Jesus was telling Thomas: Touch, touch… What do you touch? You touch the man! If you want to touch God, you must believe.” Thomas immediately takes the leap of faith and utters the best confession of faith in the divinity of Jesus in the entire New Testament: “My Lord and my God”. Then Jesus said: “Blessed are those who without seeing, yet believe” (John 20:27-29).

“Show us the Father”

There is this moving dialogue of Philip with Jesus, during the Last Supper, in the Gospel of John. Philip asks Jesus: “Lord, show us the Father and we will be satisfied.” This request is very touching in the context of the invisibility of God which we have seen in the Old Testament, the polemic against the idols and the pagans’ challenge “Were is your God?”

Then Jesus answers: “Have I been with you so long, and yet you do not know me, Philip? He who has seen Me has seen the Father; how can you say: ‘Show us the Father? Do you not believe that I am in the Father and the Father is in Me?” (John 14:8-10).The divinity of Jesus is really the center of the New Testament, and only somebody blinded by prejudice can fail to recognize it.

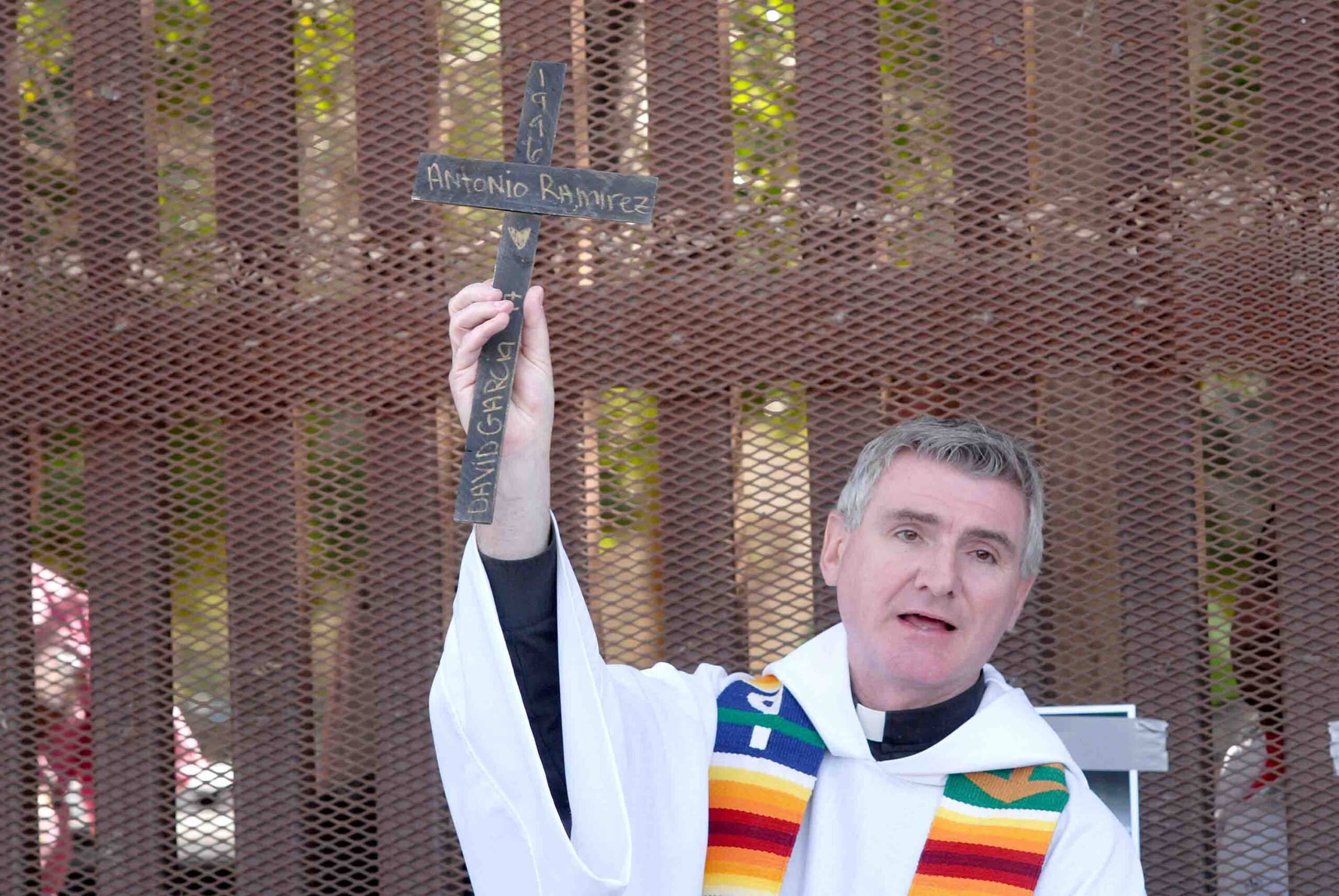

Jesus is “the image of the invisible God” (Colossians 1:15). The humanity of “God with us” is the reason of the images of Jesus Christ and consequently Mama Mary and the Saints in the Catholic Church. In the 8th century, there was a struggle about the problem of the images. The movement that forbade images called Iconoclasm was condemned by the Pope and the images remained as a Catholic tradition which gave origin to the masterpieces of art through the centuries.

Strictly speaking, there is no image of God, but only of Jesus, the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Saints. The opposition to the images, if pushed to the extreme, results in the denial of the Incarnation as it is in Judaism, Islam and also in some sects which consequently cannot call themselves Christian any more.