The funeral of Pope John Paul II was held on April 8, 2005, six days after his death on April 2. He had lived the last years of his long pontificate being increasingly incapacitated by Parkinson’s disease and other painful complications. Death, when it came for the great pope, was a liberation.

The body of John Paul II was exposed first in the papal residence where it was venerated by the clergy, after which it was placed in St. Peter’s Basilica. Later, the faithful who had gathered at St. Peter’s Square were allowed to enter the Basilica to pray before the exposed body. The Swiss Guards remained always beside the body while it was exposed for viewing. By April 6, a million people had seen John Paul II’s remains lying in state in St. Peter’s Basilica.

Applause rang out in the wind-whipped square as John Paul’s plain cypress coffin, adorned with a cross and an “M” for the Virgin Mary, was brought out from St. Peter’s Basilica by the papal gentlemen and placed on a carpet in front of the altar for the requiem mass. While the book of the Gospel was on the coffin, the breeze fluttered its pages.

Gratefully applauded

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Dean of the College of Cardinals, a close confidant of John Paul and who became his successor, presided over the requiem mass. After the Gospel, he stood up to preach and referred to John Paul as our “late beloved pope” in a homily that traced the pontiff’s life from his days as a factory worker in Nazi-occupied Poland to his final days as the head of the world’s more than one billion Catholics.

The usually reserved German-born Ratzinger choked as he recalled one of John Paul’s last public appearances. He said: “None of us can ever forget how in that last Easter Sunday of his life, the Holy Father, marked by suffering, ambled to the window of the Apostolic Palace and for the last time gave his apostolic blessing. We can be sure that our beloved pope is standing today at the window of the Father’s house, that he sees us, and blesses us. Yes, bless us, Holy Father. We entrust your dear soul to the Mother of God, your Mother, who guided you each day and who will guide you now to the eternal glory of her Son, our Lord Jesus Christ.”

Cardinal Ratzinger became emotional in other parts of his homily, especially when referring to the inability of Pope John Paul to speak during the last days of his life. He said John Paul was a “priest to the last” and that he had offered his life for God and his flock “, especially amidst the sufferings of his final months.”

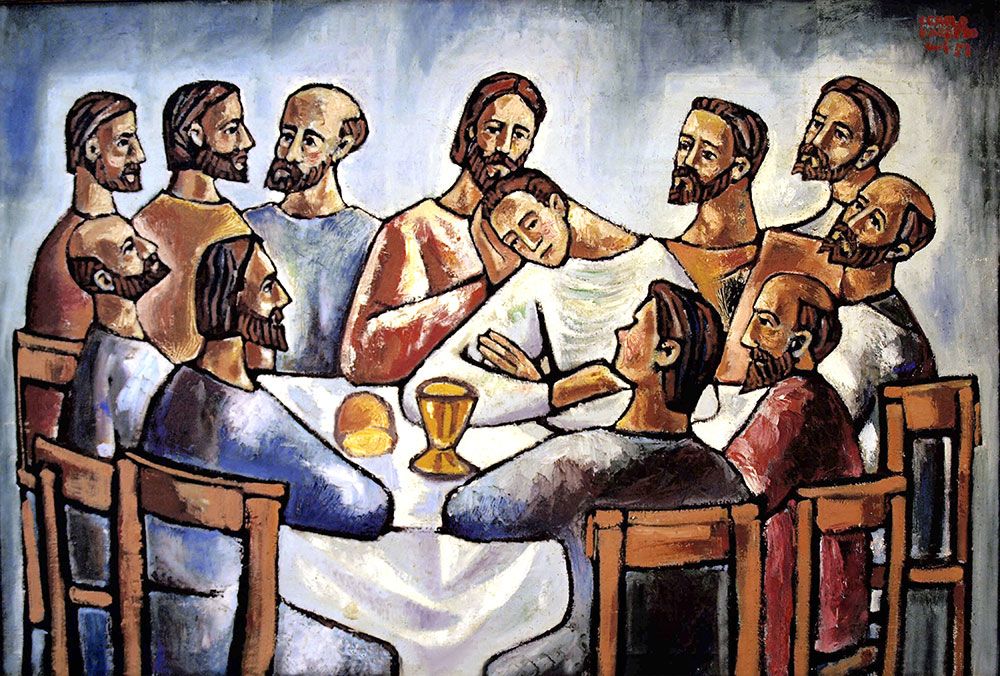

Altogether, the homily was interrupted ten times with outbursts of applause. The Nicene Creed sung in the Latin language followed the homily. The prayers of the faithful were offered in Italian, French, Swahili, Tagalog, Polish, German, and Portuguese, showing the breath of universality of the Catholic Church.

“Santo Subito”

After the liturgy of the Eucharist, the crowd burst into applause, waving flags and banners, chanting, “Santo Subito!” which means “Saint now!” Then, the papal gentlemen carried the Pope’s coffin towards the entrance of St. Peter’s for interment. At the door, the coffin was turned 180 degrees to face the congregation and the cameras, and the crowd applauded and cheered with more fervor their farewell, before it was taken out of the public view for the last time.

Pope John Paul’s funeral brought together what was, at the time, the single largest gathering in history of heads of states outside the United Nations. Four kings, five queens, at least seventy presidents and prime ministers, and more than fourteen leaders of other religions attended, alongside the faithful. It is likely to have been one of the largest single gatherings of Christianity in history, with numbers estimated in excess of four million mourners gathering in Rome alone.

Turbans, fezzes, yarmulkes, black lace veils, or mantillas, joined the “zucchettos,” or skullcaps of Catholic prelates on the steps of St. Peter’s in an extraordinary mix of different people from around the world. “I’m here because I’m a believer but also to live a moment in history,” said Stephan Aubert, wearing a French flag draped over his shoulders.

Rome itself was at a standstill as extraordinary security measures were put in place. Since the beginning, a ban on vehicle traffic in the city center took effect. Airspace was closed, and anti-aircraft batteries outside the city were on alert. Naval ships patrolled both the Mediterranean coast and the Tiber near Vatican City, the tiny sovereign city-state encompassed by the Italian capital.

Rome groaned under the weight of visitors. Side streets were clogged in a permanent pedestrian rush hour, mostly by young people with backpacks. Tent camps sprang up at the Circus Maximus and elsewhere around the city to accommodate the spillover from hotels. Giant digital screens were hoisted at several sites in Rome and at designated campsites outside the city for the millions of mourners and pilgrims.

Greatness in black and white

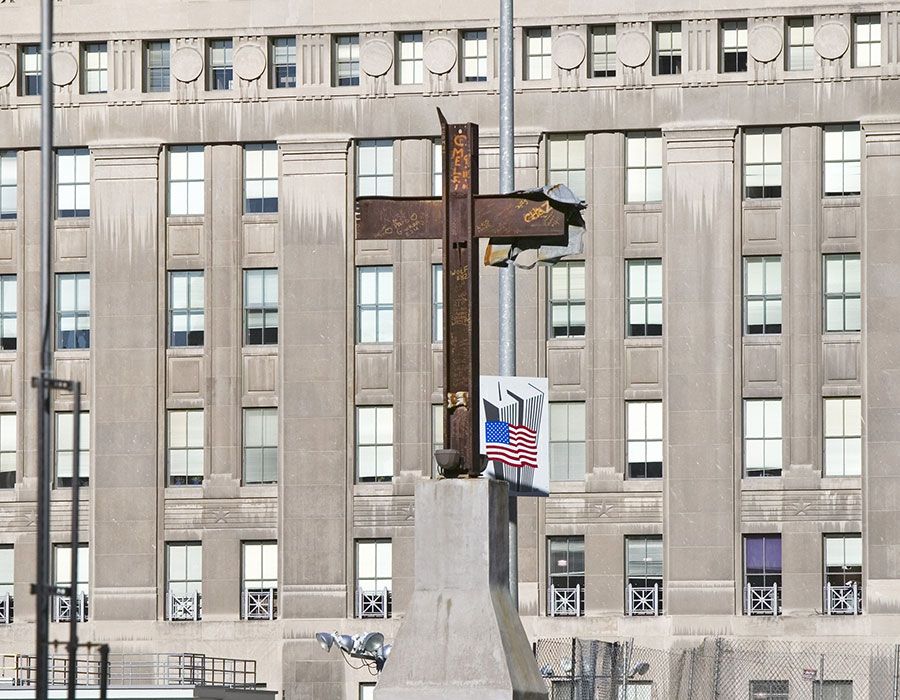

The funeral was the unique testimony of the greatness and holiness of a Church leader that has left an indelible mark in the history of the Church in the beginning of the 21st century. He was canonized, together with John XXIII by Pope Francis on April 27, 2014, only nine years after his death.

The outstanding personality of Karol, however, glossed over some grave problems that his long pontificate left unsolved and would affect his successors. For some Catholics, the pope’s uncompromising leadership had polarized the Church and delayed the necessary reforms envisaged by Vatican II.

Several members of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP) flew from the States to Rome on the occasion of the funeral. Just as the group’s members arrived at St. Peter’s Basilica, led by founder Barbara Blaine, police officers escorted them outside the confines of St. Peter’s Square. The problem will haunt the pontificate of Benedict XVI and his successor Pope Francis will publicly ask forgiveness for this sin.

The scandal of child abuse is compounded by the dramatic, terminal situation of the clergy in certain countries like Great Britain, and other European churches. Christian communities need their pastors. What about countries where the Catholic population is increasing like in Africa or the Philippines for that matter. Can one priest cope with a parish of 50.000, or 100.000 faithful, or even 150.000 like it is in Metro Manila?

The problem is on the table of Pope Francis who seems to have revived the enthusiasm of the time of Vatican II with his view of a synodal church. Pastoral commitments have become his mission. The concerns of liberation theology that John Paul II didn’t accept because of opposition to everything even faintly communist, are now present with Pope Francis who has proclaimed blessed Archbishop Oscar Romero.

With an iron will, John Paul II set the Catholic Church on an unmistakable theological course with regard to dogma, sexuality, contraception, and the unmitigated power of the pope himself. Yet the signal sent out was not unilateral. For certain aspects, he was clearly a reformer. He has governed the Church conservatively yet many of his other attitudes are progressive.

The fearless innovator

During his papacy, Pope John Paul II had done more to mount a moral critique of global capitalism than any other leader, as the Catholic Church confirmed its concern for the poor. He tirelessly promoted religious liberty, while the doctrine of human rights has become the platform of his preaching to the world. Far from being always a conservative, he was indeed an innovator.

The other part of the puzzle is the saintly pope’s lack of success in his on-going struggle with the inexorable tide of secular materialism. He has tried repeatedly to point to the beauty and idealism of the Gospel, but his message in the developed world has fallen on deaf ears. Mass attendance and vocations to religious life and the priesthood continued to decline in Western Europe, the cradle of Roman Catholicism, and North America. Pope Benedict XVI called it “relativism” and Pope Francis is struggling with it with his approach of mercy.

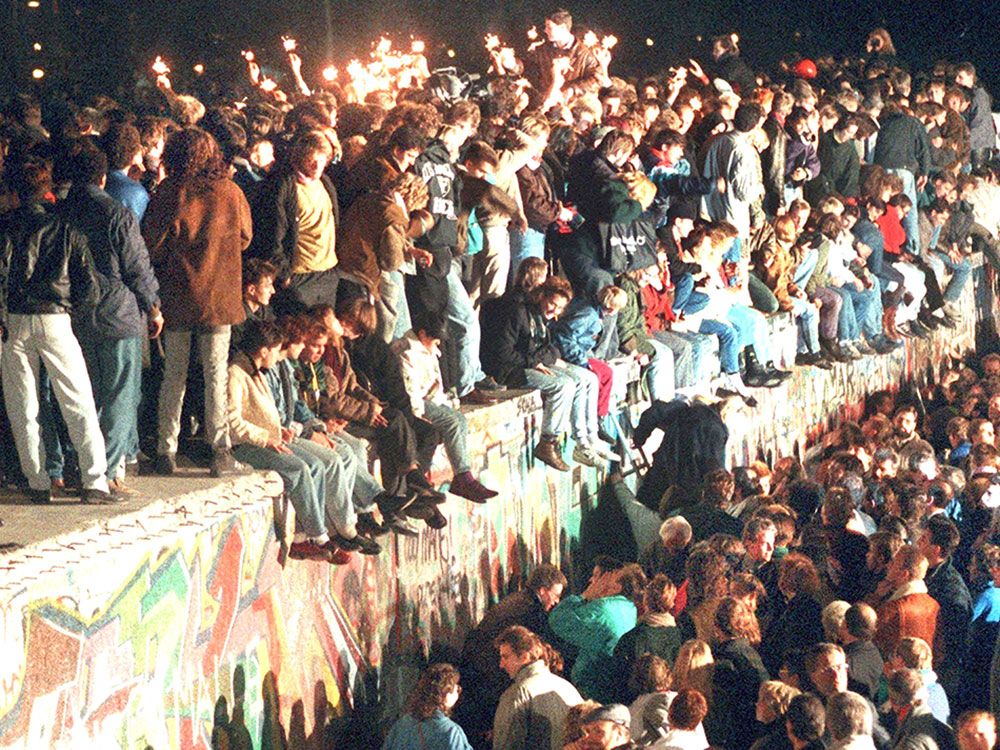

What made this dawning realization particularly bitter for John Paul II is that as the ideology of communism rolled back in Eastern Europe (and he fought mightily for it!), the faithful did not celebrate their newly found freedom in church, but increasingly turned their back on what had sustained their identity.

He was a man for whom discipline ensured the survival of a Church under persecution and repression– the experience he shared with the global Church. But the problems the Church faced from individualism and consumer capitalism were and are still of a different order, and remained as challenges also for his successors.