I begin with an embarrassing fact: my predecessors in the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus were slave owners. In the early nineteenth century, they had plantations in the American South where Negro slavery was normal, and the plantations were worked by Negro slaves. Moreover, when debates broke out over the morality of slaveholding, there were Jesuits who stoutly defended it, appealing to St. Augustine, to St. Thomas Aquinas and to our founder St. Ignatius Loyola.

I cite this example to point out the power which culture and tradition, “the way things have always been,” have on the moral judgments even of educated and holy men. Slavery had been a fact of life in biblical times and throughout the history of Europe, as it was in the Philippines, and it would have been hard to imagine a society without it. It took centuries of moral reflection to bring about a change in mentality, and a bloody Civil War in the United States to bring about the demise of slavery there.

Pope Benedict XVI, in his first social encyclical, Caritas in Veritate (No. 4), points to the function of truth in countering the effect of culture and tradition as one building a just and peaceful society: “Truth, by enabling men and women to let go of their subjective opinions and impressions, allows them to move beyond cultural and historical limitations and to come together in the assessment of the value and substance of things. Truth opens and unites our minds in the logos of love: this is the Christian proclamation and testimony of charity.”

Good news to the poor

It is the role, then, of Catholic social thought to guide and speed up moral reflection, based on the Gospel and human experience together with the social sciences, and so to move our world a step closer to the Kingdom which Christ proclaimed in His “inaugural address” (Lk. 4:18-19): “The Spirit of the Lord is upon Me, because He has anointed Me to preach Good News to the poor. He has sent Me to proclaim release to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed, to proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord.”

Since the publication of the first formal social encyclical, Rerum Novarum, in 1891, key principles have emerged and been integrated into a coherent whole. Fundamental are the dignity and freedom of the human person, but also his or her social nature as a member of society and community. Then comes the virtue of solidarity, concern for others and for the good of all. Work is a source of growth for the individual and contribution to the community, and workers should receive wages adequate for their family needs. Created goods are for the good of all, and this comes before the right of private property which is only a way of organizing their use. The environment is God’s gift, to be used and cherished, not exploited. The State is to provide the opportunities and conditions for genuine human development. But it should not attempt to solve all problems lest it deprive individuals and smaller communities of their freedom and initiative. Moreover, the State should have particular concern for the poor.

Two additional principles perhaps deserve direct quotation: on democracy and on popular movements.

Ω “The Church values the democratic system inasmuch as it ensures the participation of citizens in making political choices, guarantees to the governed the possibility both of electing and holding accountable those who govern them, and of replacing them through peaceful means when appropriate. Thus, she cannot encourage the formation of narrow-ruling groups which usurp the power of the State for individual interests or for ideological ends…. Authentic democracy is possible only in a State ruled by law, and on the basis of a correct concept of the human person.” (Centesimus Annus, No. 46.)

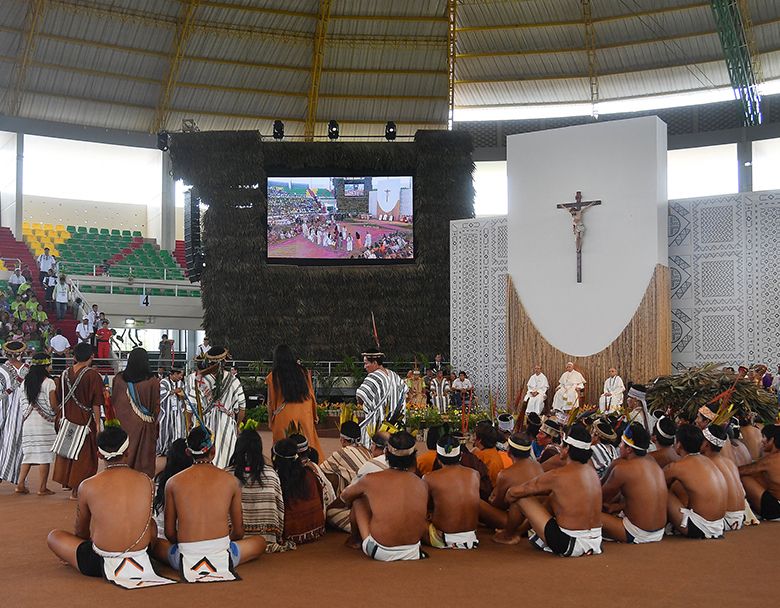

Ω “Positive signs in the contemporary world are the growing awareness of the solidarity of the poor among themselves, their efforts to support one another and their public demonstrations on the social scene which, without recourse to violence, present their own needs and rights in the face of the inefficiency or corruption of the public authorities.” (Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, No. 39.)

Show the Lord a newspaper

A little reflection will show how far we are, the only Christian nation in the Far East, from living the Gospel of the Kingdom and incorporating it into the structures of our society. To make the reflection more realistic, one might imagine taking Jesus Christ on a sight-seeing tour. Show Him the beautiful homes in Corinthian Gardens and Forbes Park, the full-page advertisements in the newspapers, replete with snob appeal, for luxurious condos and suburban villages with foreign-sounding names. Then take Him to the miserable hovels of scavenger families in Payatas, reeking with filth and TB germs, the children gaunt and sick. Have the Lord look over a newspaper and see, side by side with accounts of malnutrition among children, advertisements for slimming program for those who are eating too much!

Hear the Lord ask you: “How can it be that a society which calls itself by My name, Christian, can permit such gross inequalities in the distribution of goods which were created for all, such violations of the dignity of human beings made in My image?”

The problem is not limited to the distribution of income. It extends to land ownership, health and educational services, rights before the law, and political participation. And, as His Eminence Gaudencio Cardinal Rosales and the bishops of Manila have suggested in their pastoral letter on urban planning and development policies (See sidebar story), the living standards of most of us are subsidized by these structures of injustice. Our homes and offices, schools and churches, would cost far more than they do if the workers who build them received wages sufficient for them to live in legal housing rather than to squat in danger areas along the waterways. The newspaper which we read would cost more than it does if the scavengers at Payatas collecting old papers for recycling were to receive incomes sufficient for them to live in decency. And so with the rest of the urban work force – the jeepney and bus, taxi and tricycle drivers, market vendors, police, firemen and security guards – aside from our small farmers and landless agricultural workers.

The virtue of solidarity

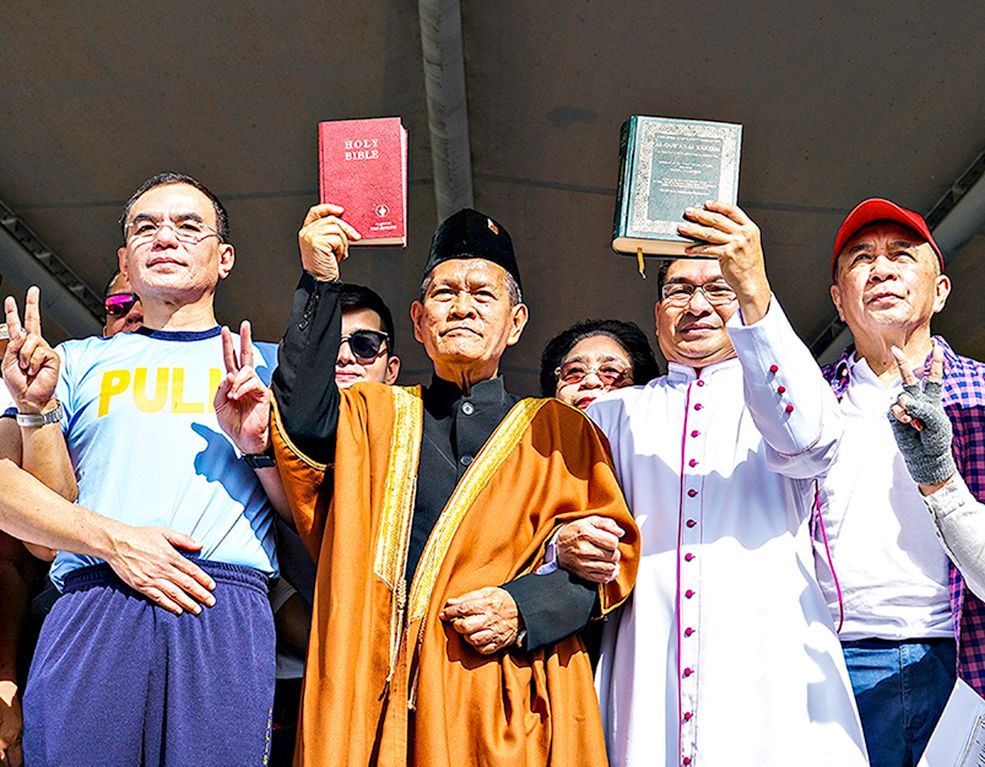

These “structures of sin,” as Pope John Paul II called them, are woven into the fabric of our society, just as slavery was woven into the fabric of the American South. We all profit by them and have a duty before God to change them. But change will not come from individual acts of charity alone, praiseworthy as they are. Nor will it come simply by changing the leadership at the top of our society. It must begin with a change of heart throughout our society, a cultural change, the virtue of solidarity. It must incorporate the efforts of the organized poor themselves as the popes have said, supported in solidarity by the churches, the media, academe, the legislators and judges, by local and national government officials, by political parties with concrete programs and accountable to the people.

Change, it has been wisely said, takes time; so, therefore, there is no time to lose. Where shall we start? Jesus Christ awaits our answer.