God made every kind of wild animal, every kind of tame animal, and every kind of thing that crawls on the ground. God saw that it was good” (Genesis 1: 25). Indeed, for Him, they were precious. Before the Deluge, He gave Noah precise instruction to save all of them, together with his own family, leaving behind the humans who had displeased Him so much. In the mythological language of creation and recreation, this shows that wild beasts have their own role to play – if they were merely ornamental and disposable, the domesticated ones would be enough to keep the new humanity alive. But God’s creation is not about utility. It’s a masterpiece of natural balance, and a permanent source of wonder and awe, and also a way to discover, in its infinite diversity and beauty, His bounty and the wonders with which He filled our planet – His secret signature.

Right now, I would be quite able to build a new ark, and to exclude all the soulless beings that are decimating our wild friends, just for the sake of making more money. Before, however, I would try to join the culprits and explain to them that money is just paper, and it doesn’t feed our need of beauty and mystery nor the dreams of our children. I doubt that they would understand, but at least I would have tried. Full disclosure: I’m emotionally involved in the question, and quite grumpy about the present state of things. After all, we are facing the biggest extinction of species since dinosaurs disappeared from the face of the earth. It’s a deluge in reverse mode, and on such a big scale that we are only able to concentrate on the most emblematic ones.

The last time I felt like that was in 2012, when King Juan Carlos of Spain was caught red-handed, in the company of a female friend, on a secret trip to Botswana to kill an elephant, which is an icon of the wonders of wildlife and one which is on the fast track to extinction. I don’t know if it was to show, in his old age, his machismo or to kill, together with the poor beasts, his boredom. The news caused a stir in his own country, then, as now, at the peak of a huge and hurtful recession. Those escapades, which targeted endangered species, were quite common (in Spain there are large hunting reserves where you can shoot the legal ones), even though the king, ironically, was also honorary president of the Spanish chapter of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). At once, a petition appeared on the internet asking for his dismissal (disclosure: I signed it at once), and a few months later the conservation groups’ chapter “voted overwhelmingly to abolish the post.”

THE CRIME THREAT

Unfortunately, punishment doesn’t usually follow “crime” in such a swift way. Mainly because, according to WWF, the racket behind the illegal traffic of wild species is the same that operates in the shadows, and deals with everything highly lucrative. The organization warns: “The world is dealing with an unprecedented spike in illegal wildlife trade, threatening to overturn decades of conservation gains. Ivory estimated to weigh more than 23 metric tons – a figure that represents 2,500 elephants – was confiscated in the 13 largest seizures of illegal ivory in 2011. Poaching threatens the last of our wild tigers that number as few as 3,200. Wildlife crime is a big business. Run by dangerous international networks, wildlife and animal parts are trafficked much like illegal drugs and arms (and also human beings). By its very nature, it is almost impossible to obtain reliable figures for the value of illegal wildlife trade. Experts at TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring network, estimate that it runs into hundreds of millions of dollars.

Some examples of illegal wildlife trade are well known, such as poaching of elephants for ivory, tigers for their skins and bones, and rhinos for their horns. However, countless other species are similarly overexploited, from marine turtles to timber trees. Not all wildlife trade is illegal. Wild plants and animals from tens of thousands of species are caught or harvested from the wild and then sold legitimately as food, pets, ornamental plants, leather, tourist ornaments and medicine. Wildlife trade escalates into a crisis when an increasing proportion is illegal and unsustainable – directly threatening the survival of many species in the wild. Stamping out wildlife crime is a priority for WWF because it’s the largest direct threat to the future of many of the world’s most threatened species. It is second only to habitat destruction in overall threats against species survival.”

HORNS AT GOLD PRICES

It’s almost hard to believe, but the rhino horn is considered a sort of fix-it-all potion for all kinds of “diseases,” as is described in a 16th. century Chinese handbook: “As an Antidote to Poisons; to cure devil possession and keep away all evil spirits and miasmas, for gelsemium [jasmine] and snake poisoning; to remove hallucinations and bewitching nightmares; continuous administration lightens the body and makes one very robust; for typhoid, headache, and feverish colds; for carbuncles and boils full of pus; for intermittent fevers with delirium; to expel fear and anxiety, to calm the liver and clear the vision. It is a sedative to the viscera, a tonic, antipyretic. It dissolves phlegm. It is an antidote to the evil miasma of hill streams; for infantile convulsions and dysentery. Ashed and taken with water it treats violent vomiting, food poisoning, and overdosage of poisonous drugs; for arthritis, melancholia, loss of the voice. Ground up into a paste with water, it is given for hematemesis [throat haemorrhage], epistaxis [nosebleeds], rectal bleeding, heavy smallpox, etc.”

Once, Hong Kong was the destiny of this illegal trade, but now it has found new competitors: Taiwan and Korea. As the author Richard Ellis wrote: “Taiwanese self-made millionaires are notorious for their conspicuous consumption of rare and exotic wildlife, and the Chinese traditional adage that animals exist primarily for exploitation is nowhere more pronounced than in Taiwan. Most of the rhino horn for sale there comes from South Africa. The demand for Asian horn, in particular, is increasing and wealthy Taiwanese, aware that prices will rise even higher as rhinoceros numbers decline, are buying it as an investment. In those regions where rhino horn products are dispensed – legally or illegally – the most popular medicines are used for tranquilisers, for relieving dizziness, building energy, nourishing the blood, curing laryngitis, or simply, as the old snake-oil salesmen would have it, “curing whatever ails you” (…) The Taiwanese make up much of the market for horn imported to Asia from South Africa, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe – wherever black rhinos can still be found. Like the Taiwanese, many Koreans are devoted practitioners of traditional medicinal arts, and are prepared to import substantial amounts of substances not naturally found in their country. Korean traditional medicine is based on the Chinese version, which is said to have come to Korea during the sixth century.” Meanwhile some centuries have passed.

The consequent carnage is staggering: rhino poaching in South Africa increased by 5,000% between 2007 and 2012, according to the WWF. Whoever sees the carcasses of the slaughtered noble beasts rotting in the sun just because a small part of its body has “magic” properties, feels, I’m certain, a mixture of disgust, nausea and disbelief. The same applies to the noble elephants, robbed of their tusks to make dubious artifacts. The oh so beautiful tigers, also have a decorative value – the nouveaux riches like to have a skin, with the mouth wide open, in the living room, in front of the fireplace.

TIGER’S PHARMACY

Unfortunately, tigers are also used as medicine: “For more than 1,000 years the use of tiger parts has been included in the traditional Chinese medicine regimen. Because of the tiger’s strength and mythical power, the Chinese culture believes that the tiger has medicinal qualities, which helps treat chronic ailments, cure disease and replenish the body’s essential energy. Chinese texts state that the active ingredients in tiger bone; calcium and protein, which help promote healing, have anti-inflammatory properties.” In fact, the same can be said about a common Aspirin.

Unlike the rhino, almost all the tiger parts have “curative” uses. Some examples: claws – used as a sedative for insomnia; teeth – used to treat fever; fat – used to treat leprosy and rheumatism; nose leather – used to treat superficial wounds such as bites; bones – used as an anti-inflammatory drug to treat rheumatism and arthritis, general weakness, headaches, stiffness or paralysis in lower back and legs and dysentery; eyeballs – used to treat epilepsy and malaria; tail – used to treat skin diseases; bile – used to treat convulsions in children associated with meningitis; whiskers – used to treat toothache; brain – used to treat laziness and pimples; penis – used in love potions such as tiger soup, as an aphrodisiac; dung or feces – used to treat boils, haemorrhoids and cure alcoholism.

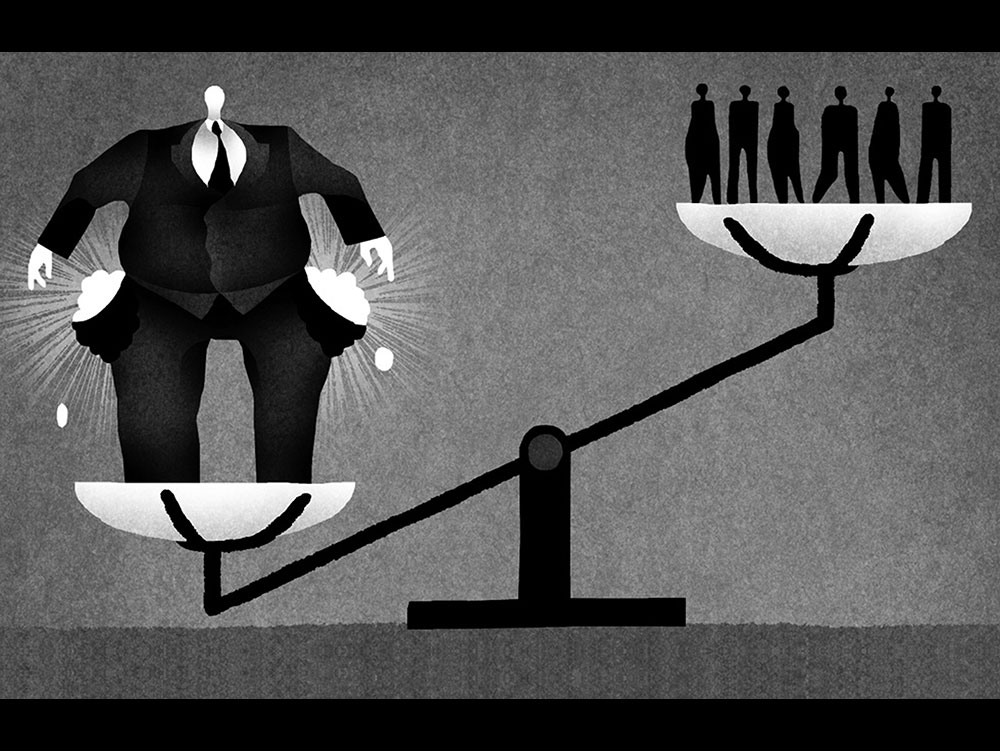

The trafficking mafias have at their disposal an almost infinite army of poachers, whose extreme poverty leads them to just see in wildlife a valuable barter for trade. On the other hand, there are people with lots of money to spend and no scruples. In the equation, the simple rules of the free market – offer/demand – command the game: “Rhino horn, elephant ivory and tiger products continue to command high prices among consumers, especially in Asia. In Vietnam, the recent myth that rhino horn can cure cancer has led to massive poaching in South Africa and pushed the price of rhino horn to rival gold.”

OIL IN THE PARK

Not even national parks, who are supposed to offer protection to the beasts, are safe. Along with extreme poverty, there are also wars, armed bandits, corruption, the pressure of corporate interests and the lack of a long-term view, which would easily detect in eco-tourism a constant and reliable source of revenue. Recently, in the Congo, the struggle for gold put an abrupt and bloody end to an NGO project to save the okapis in the Ituri rainforest nature reserve. Right now, WWF is trying to block oil exploration in Africa’s oldest national park, Virunga, where a remaining community of 200 gorillas live. The Swiss-based conservation group filed its complaint with Britain’s Department for Business Innovation and Skills in a bid to stop an oil and gas exploration and production company called SOCO International from exploring in the park, a World Heritage site listed by UNESCO as being “in danger.”

The WWF says SOCO’s plan violates the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s guidelines on sustainable development; the Department is the arm of the British government responsible for overseeing compliance with these guidelines. Last year, the Congo government authorized SOCO, which is based in London, to explore the region, saying that economic interests take precedence over environmental considerations. Plans to develop the area around Lake Victoria, one of the most sensitive ecological areas on the continent, are already on the table.

Because of these gorillas, whose population has been constantly shrinking (in the whole region, the estimates point to a remnant population of 700), several environmentalists and park guards have been violently killed. Sometimes, just because the poachers wanted to sever the paws of these magnificent animals – in their societal behavior so close to humans – to sell them as ashtrays. The gorillas, even if they are not our closest relatives in the evolution process, are so human-like that this desecration of life brings to mind the unthinkable act of using the remains of one of our remote ancestors to make a lamp.

LIKE “MILK TEETH”

At the moment, there is a lot of pressure from a group of African countries to remove the ban on all ivory trade and instead to just monitor it, as it happens with the legal one. The pressure group is headed by China, but has the support of some African countries, such as South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe. Their arguments are contested by conservationists, but the profit motive is very powerful. A recent article in The Guardian was quite eloquent: “Ivory is highly desirable in China, Japan and Thailand, used for highly elaborate decorative ornaments down to small keepsakes. The legal ivory was sold to the Chinese government at auction for $175 (£112) per kg, and entered the market at $1,700 per kg, but current market prices for ivory in China range from $750 to $7,000 per kg depending on the quality. African tusks are bigger and attain a higher price than those of Asian elephants. With an increasingly affluent and growing middle class more than willing to pay for ivory, demand has never been stronger.”

The pressure group argues that legalising all ivory trade would put a stop to the violence, smuggling and crime generated by the illegal trade, but while some of the environmentalists keep asking for a total ban, the majority defend a middle way: “They argue that the most effective way to protect elephants is by improving monitoring systems; intelligence-led enforcement in transit countries; and widespread public education of consumers in countries such as China. “Some Chinese think tusks are like milk-teeth – they fall out and regrow with no harm to the elephant,” says Richard Thomas from the wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC.

HUMILIATED KINGS

In South Africa, another business is, shamefully, booming: lion farms. The profit motive is once more present. Patrick Barkham, from The Guardian, visited one just on the outskirts of Johannesburg, and, he had to make an effort to realize that these very cute lion cubs were being fattened to become “canned hunting,” i.e. lions that, once grown, are meant to be summarily killed by rich people willing to pay a lot to hang a trophy on the wall without experiencing any effort or danger. After that, they are able to display to their family and guests their courage, and after a few drinks they conjure up some dangerous adventure in the “savage continent.” According to Barkham, there are more than 160 of these “breeding cat” farms and the numbers speak for themselves: “There are now more lions held in captivity (5,000 up) in the country than those that live in the wild (about 2,000).” According to a quoted witness, the cubs are cheap: they are just stolen from the wild.

In itself, the practice should be a cause for national shame: “While the owners of this ranch insist that they do not hunt and kill their lions, animal welfare groups say most breeders sell their stock to be shot dead by wealthy trophy hunters from Europe and North America, or for traditional medicine in Asia (another “magic” potion). The easy slaughter of animals in fenced areas is called “canned hunting,” perhaps because it’s rather like shooting fish in a barrel. A fully grown, captive-bred lion is taken from its pen to an enclosed area where it wanders listlessly for some hours before being shot dead by a man with a shotgun, hand-gun or even a crossbow, standing safely on the back of a truck. He pays anything from £5,000 to £25,000, and it is all completely legal.”

We started this text with the deserved humiliation of a human king, and we end it with the undeserved and shameful one of a noble animal that, with reason, is known as the king of the jungle.