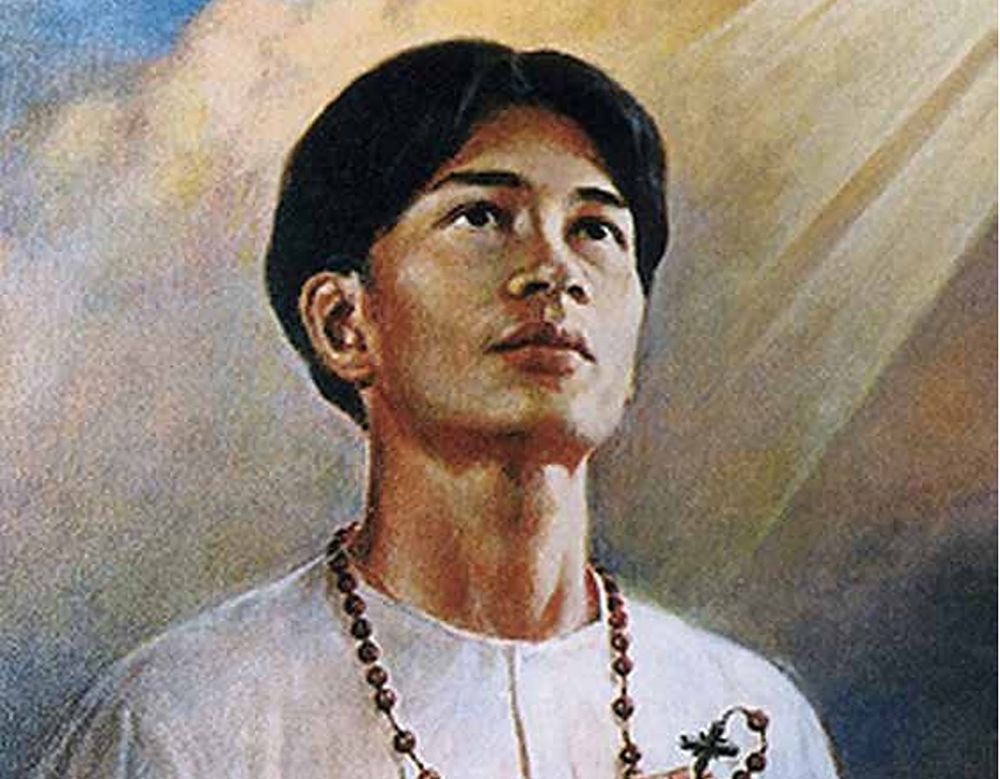

St. Joseph was confronted with deeply displacing situations which upset his life and expectations: the mysterious pregnancy of Mary, the experience of exclusion at the birth of Jesus, and Herod’s persecution.

As a righteous man, that is, one totally dedicated to do the will of God, St. Joseph was first of all a man of discernment; his dreams represent the mystery of the interruption of God within human experience. Secondly, he welcomed God’s plan, even though he was not able to explain it. He dreamt a future, unheard of, in the midst of puzzling contradictions; a future in which God is thoroughly involved for the salvation of all.

He discerned God’s will, set off at once, and embraced the “disturbing” situations. Such a culture of care starts with listening to the Word and putting it into practice right away. St. Joseph took care of the fragility of life with creative courage, and that is the way of communion with God and humanity.

We associate the icon of St. Joseph with the spiritual meaning of work. What comes to our mind is the image of an artisan, a skilled carpenter who provided for his family, rendered a service to the community, and participated in the creative work of God in the world. All that affirms the sense of dignity of the worker, nurtures hope in the coming of the Kingdom of God and life-giving relationships. Thus, we understand the devastating impacts of unemployment in the life of many people; sometimes these impacts go far beyond the deprivation that prevents people from meeting their basic needs.

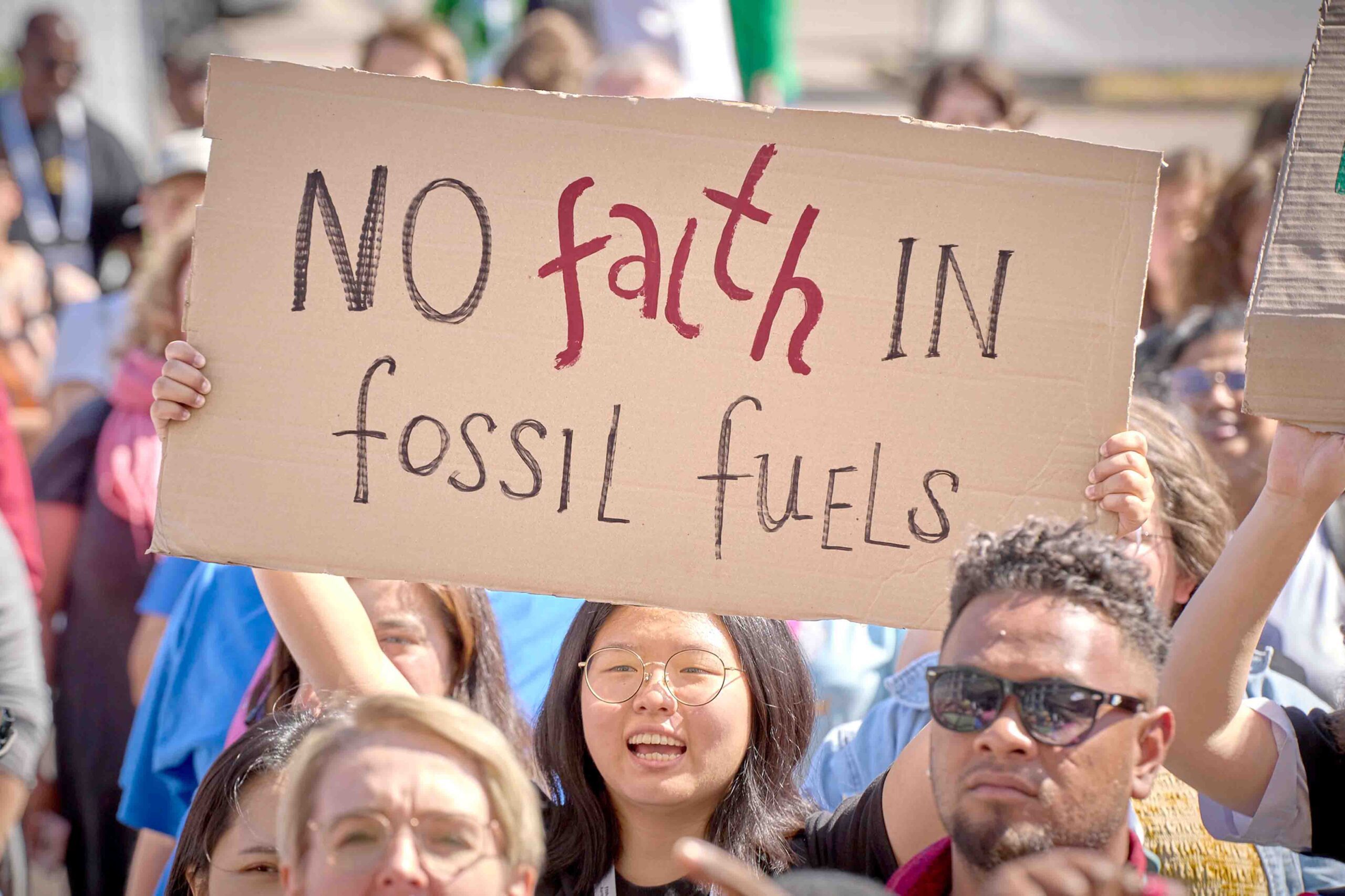

Unsustainable Economic System

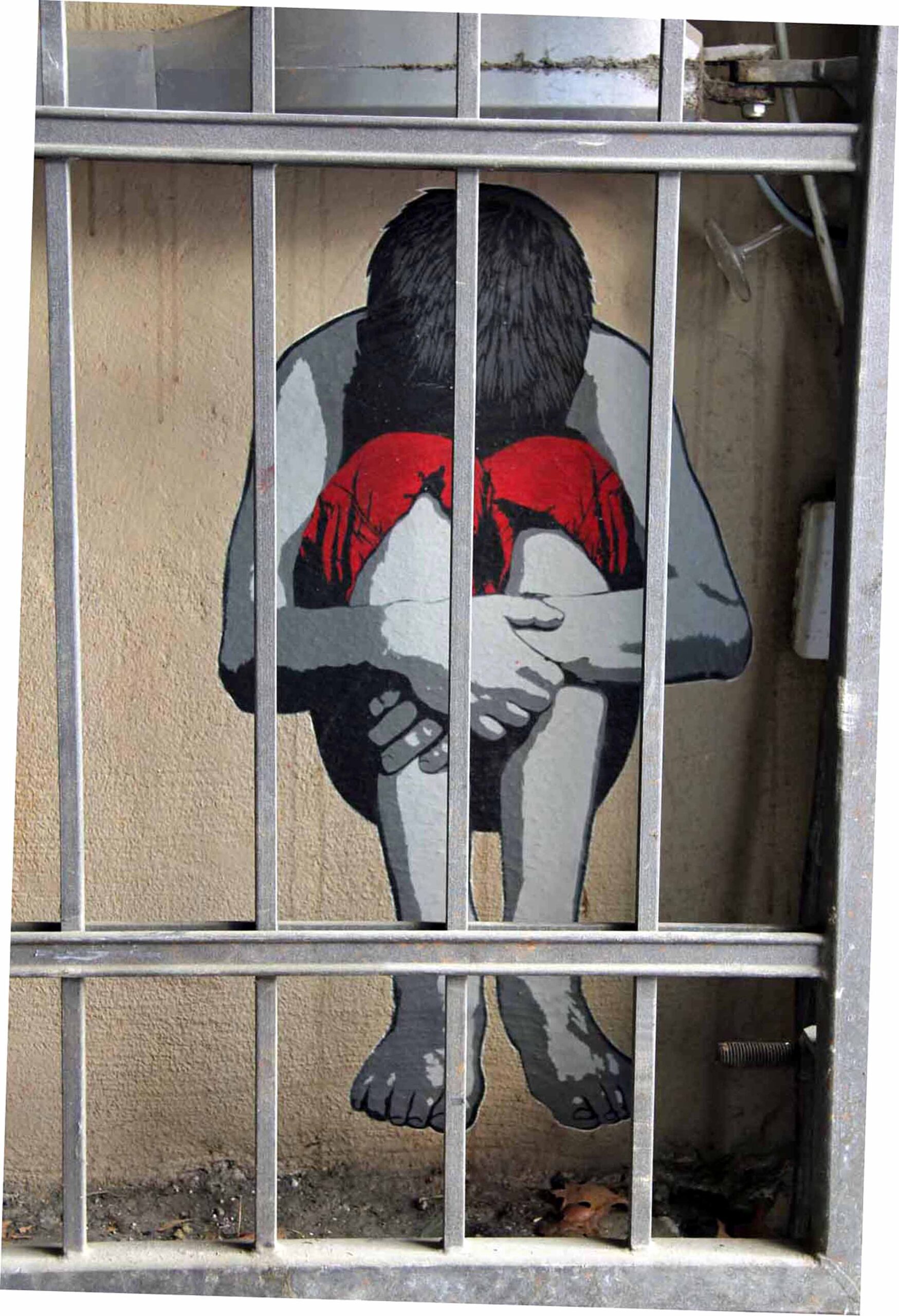

Nowadays, we are globally experiencing daunting situations of which we can hardly see the end. Most certainly the COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated the effects of an unsustainable global economic system that keeps on widening the gap between the rich and the poor, generating ever more unemployment and environmental devastation; “such an economy kills” said Pope Francis in Evangelii Gaudium (EG) 53. Today, he added, “everything comes under the laws of competition and the survival of the fittest, where the powerful feed upon the powerless. As a consequence, masses of people find themselves excluded and marginalized: without work, without possibilities, without any means of escape. Human beings are themselves considered consumer goods to be used and then discarded. We have created a “throw away” culture which is now spreading. It is no longer simply about exploitation and oppression, but something new. Exclusion ultimately has to do with what it means to be a part of the society in which we live; those excluded are no longer society’s underside or its fringes or its disenfranchised–they are no longer even a part of it. The excluded are not the ‘exploited’ but the outcast, the ‘leftovers’. (EG 53)

Sustainable Human Settlements

Speaking about the excluded and marginalized, I can recall my missionary experience in Kenya, where I spent 18 years as a Comboni Missionary Brother working with slum dwellers in their struggle for dignified life and a decent place to live.

It is a struggle that started with resistance to land grabbing, to unfair evictions, and with the community organizing itself for bringing about more just and sustainable human settlements in the slums of Nairobi. When I left Kenya in 2015, that social movement had at last achieved some remarkable breakthroughs in the form of innovative pilot projects.

Among these, I recall a slum upgrading project in Kibera. Kibera is the biggest slum in Africa which is crossed by the railway. A narrow line surrounded by shacks in-between the passing of trains is used as a marketplace. The Railway Company wanted to reclaim the land reserve at the sides of the railway line and build two tall walls to prevent people from encroaching. That would have meant the eviction of thousands of people, remaining stranded in terms of both housing and their livelihood tied to their informal economic activities in the slum.

Through the mediation of various actors, the organized slum dwellers were able to negotiate a win-win solution with the Railway Company. The land reserve was to be left free, and two long three-storey buildings would enclose it, with no openings on the side of the railway. In that way, upgraded housing would allow accommodation for all residents and–for the first time in Kenyan history–without any relocation.

Economic activities would find a place at ground level, so that residents would retain their capacity to pay their monthly rent. In fact, to prevent gentrification mechanisms, residents were not given immediate property of their house, but they would eventually acquire it under a rent-purchase agreement over a period of many years so as to keep the rent at a similar level as before the upgrading. As I left Kenya, the project was in the rollout phase.

Corruption And Setbacks

In 2018, I had the chance to visit Nairobi (Kenya) and so I went to see the upgrading project that was almost complete. By then, it had become controversial. Corruption affected the project; people who were not entitled to receive a house ended up with a unit in the estate.

Others “had sold their poverty,” meaning, they accepted money to allow outsiders to take their place illegitimately. But when they saw that the new houses were being occupied, big arguments rose and accusations were traded. Furthermore, it turned out that some sections of the project could not be built because of the instability of the terrain, which led to the choice of reducing the living space of each unit from two to one room in order to accommodate all residents.

That, however, led to some doubts concerning how minimal standards can be. Two other setbacks for which the project suffered were the government’s refusal to have economic activities housed at the ground floor along the settlement, and the solution of underground passages to cross the railway instead of pedestrian bridges over the railway line, which would have ensured better security for residents. I left Kenya with great hope and expectations. But on seeing how things eventually turned out, I felt disappointed and sad because of what it could have been and instead it never was.

Limitations And Failures

I like to think of that as the experience of the “viscosity” of reality in its mysterious complexity of a sense of existence with its lights and shadows. One of the residents of the project helped me to accept that basic element of life. Was it because of his enthusiasm and sense of pride for the new dignified home? Or was it because of his confidence and trust in providence that made him see beyond limitations and failures?

He could actually rejoice and celebrate for the signs of the Kingdom of God transfiguring the limitations and weaknesses in the light of God’s tenderness. Probably, above all, there was a sense of fulfilment for having been involved in taking responsibility and being among the main agents of that transformation. Through his own work together with many others, gathered in a community of solidarity, he reclaimed his subjectivity as co-creator, with God, of a more just and fraternal world. Definitely, the outcomes were not as “perfect” as they could possibly have been, but the process is more important than the immediate results.

A superficial reading of reality can often give the impression that the world is at the mercy of the strong and mighty, but the “good news” of the Gospel consists in showing that, for all the arrogance and violence of worldly powers, God always finds a way to carry out his saving plan. This is also what the model of St. Joseph reminds us. It invites us to trust God, who can regenerate the world even through our fragility, weakness and limitations. Even in the midst of the storms of life, we should not fear to leave God at the helm of our journey. At times we may wish to be in control, but God always has a greater horizon. Through obedience to God’s will, we shall overcome our anxieties, our wounds, and become instruments for the Kingdom of God.