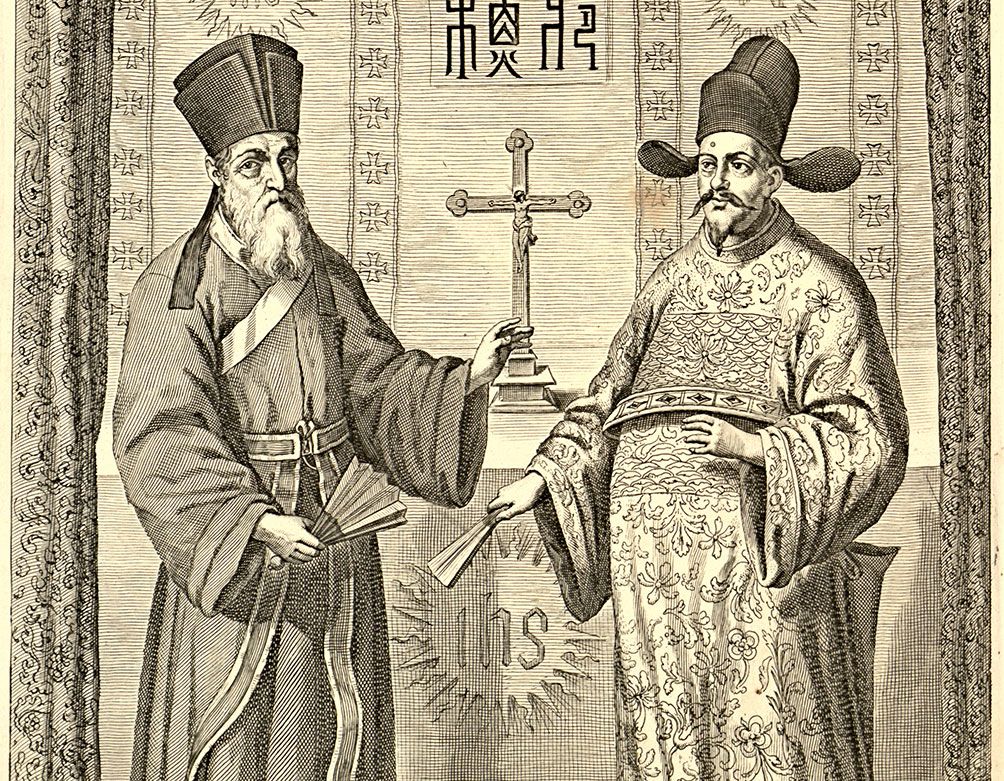

What does it mean to be Catholic in China? How do you define the relations between the ‘official’ and ‘clandestine’ churches? Is Catholicism in China still seen as a foreign religion, a threat to the State and the Communist Party, or is it already tolerated as an ‘indigenous’ church?

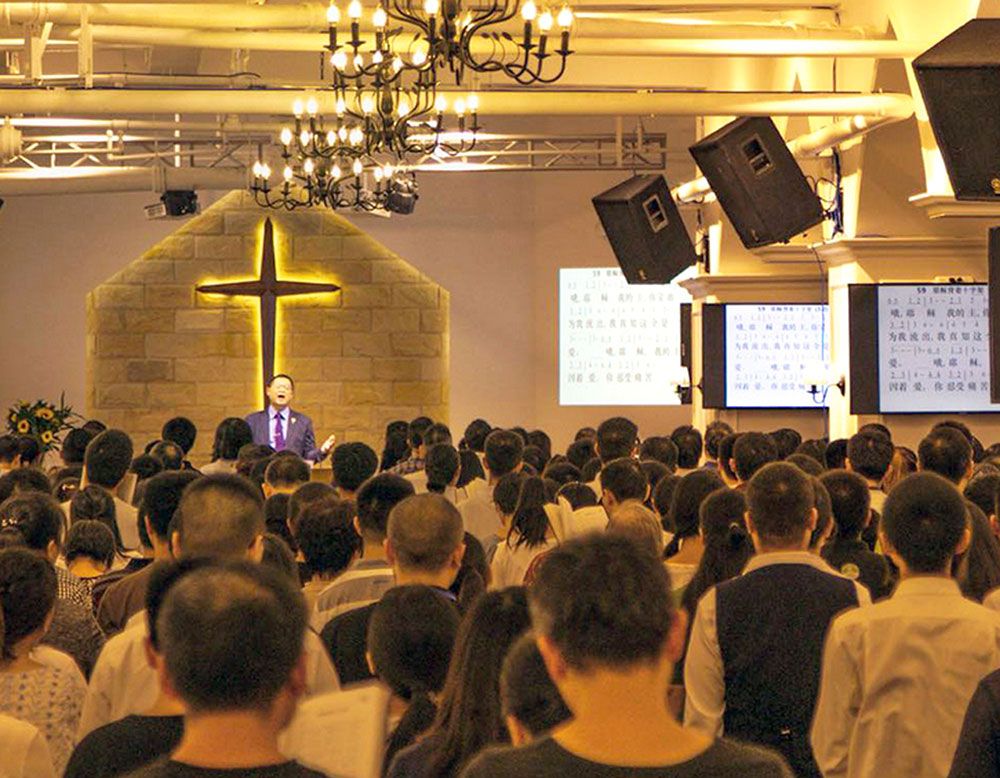

The current status of Catholicism in China remains, to a large extent, that of a religion “on the margins.” From the nineteenth century until the exodus towards the cities, in the first decade of the twenty-first century, we see Catholicism that developed in the countryside, popular and rural, that strongly maintained its own traditions. But the exodus towards the cities has profoundly shaken the traditional structure of Chinese Catholicism.

The division between ‘clandestine’ church and ‘official’ church is not as clear as it is usually said. The opposition may be strong in certain provinces and mitigated in others. Local traditions, the wounds of the past, sometimes not yet healed, play a large role. It is not a question of dogma, but a difference in the appreciation of opportunities, of concessions acceptable or not, which depend in part on the attitude of the local authorities.

The ‘official’ church will have about 1,900 priests, while the ‘clandestine’ church will have about 1,200. Anthony Lam Sui-ki, a researcher at the Holy Spirit Center in Hong Kong, estimates that, at present, the Catholic population is about 10.5 million. Between 1996 and 2014, according to Lam’s calculations, the number of male vocations dropped from 2,300 to 1,260, while that of female vocations fell from 2,500 to 156. The number of ordinations fell from 134 in 2,000 to 78 in 2015.

In the March issue of La Civiltà Cattolica (a Jesuit magazine), you wrote an article in which you addressed the campaign of “sinicization” of religions, which many liken to “an effort to repress Christianity” in China. What do you mean by “sinicization” and why did you support this project?

I did not support it! I wrote clearly that Catholics in China should avoid two dangers: the call for a “religious sinicization” coincided with the application of more restrictive rules to the practice of religion and, in a general way, with a new emphasis on the leading role of the Communist Party in all aspects of social and cultural life. In this context, we can understand that the appeal has faced resistance from many religious sectors: there are obvious dangers associated with the blind fulfillment of a policy dictated from above, which may lead to a loss of substance in the very essence of faith and personal identity. No religion can become a mere instrument of a political apparatus. Christian churches have sometimes fallen into this trap, in cultural and historical contexts, eventually suffering the consequences, regardless of the nature of the political system that requires subservience. In other words, basic decency and fidelity to the core of personal convictions must necessarily guide how Christians will react to what the authorities demand of them.

However, a second trap must also be prevented: Christian churches cannot neglect the call to “sinicization” just because it emanates from government. It is true that these communities, because they have to defend themselves against all kinds of intrusions, are more likely to adopt a defensive attitude, which makes changes and innovations impossible. The right attitude, for Christians, is probably to hear the call and evaluate the changes, imaginary and real, keeping in mind the dangers that may arise.

It is not yet clearly defined what the government expects to be the action of religious organizations and believers. There is still room for dialogue. Religious communities need to adapt to a changing environment – an urban social context, very different from the rural environment in which the Church traditionally operated. The “sinicization” of all religions is a principle adopted by the Communist Party in 2015 and solemnly reaffirmed by Xi Jinping [the leader] at the 22nd Congress in October 2017. This policy goes further into the demands and constraints it imposes which were initially foreseen.

In any case, even if this policy raises questions, we must take into account that in China everything is always evolving. Even within the party, voices are being heard so that the promised measures may be considerably eased or softened, because the risk of seeing grudges and tensions multiplied is real.

In the past two years, the Chinese Government has been accused of an “offensive against Christianity,” including church demolition, for example. Will the “sinicization” put an end to this alleged persecution?

Directives and policies are becoming more and more rigid. They are creating and they will create more tensions. However, we must avoid an apocalyptic description of reality. The dramatization of all the news coming from China does not help the Chinese Christians, who try to “get away” from all this confusion and live their faith in their daily life.

Most communities continue to meet and pray in official churches. The situation differs from place to place, for reasons that remain unclear. But it should be emphasized that the present situation does not compare with the persecutions suffered during the Cultural Revolution [1966-1976].

How do you assess the significance and impact of the recent agreement [announced on September 22] between the Vatican and Beijing on the appointment of the Chinese bishops?

The agreement establishes a mechanism for the appointment of bishops “in the future,” which should eliminate a major source of tension seen in the past. Obviously both parties want to come to an understanding of nominations – and this will be put to the test with the first choices made.

Both parties also want to maintain the possibility of adjusting the process according to the difficulties they may encounter along the way. The exact mechanism is not known, but of course it aims for a consensus on the most appropriate candidates. This is a mechanism to build trust, allowing for new and deeper discussions. Eliminating this specific source of tension (which does not mean that all sources of tension are eliminated!) could help the dialogue between the Vatican and China on issues such as refugees and global warming. For the Vatican, we need to involve China in an active and positive way if we are to advance issues of global governance.

In a context of increasing religious tensions and constraints, this agreement is seen as a sign that the strict policies recently applied by the Chinese Government can be mitigated and balanced. Of course, all this needs to be proven. The status of the current bishops of the ‘clandestine’ Church has not yet been clarified. There may be an unwritten agreement or understanding for a greater tolerance of these bishops on the part of the Chinese Government, or the possibility of them joining a future unified Episcopal Conference. This may be the most difficult part of what remains to be done, which may explain the emphasis on the fact that the agreement is provisional. There is, therefore, much work to be done and pitfalls to avoid. However, the fact that, for the first time, China recognizes the legitimacy of the Vatican in appointing the bishops represents a very important step forward.

The Vatican seems to focus on ecclesiastical goals while China is probably still expecting a political agreement, with the reestablishment of diplomatic relations, to the detriment of Taiwan. What is your opinion?

Chinese policy has several objectives at the same time, and these objectives may be contradictory or expressed differently by one or other Chinese interlocutor. A monolithic perception of China and its objectives must be avoided. When certain limits are exceeded, it must be said clearly and, once again, more serious problems may arise in the future than the present ones. It is necessary, however, and with all vigor, to continue the dialogue, to give Catholics more space in their own society. We must remain lucid, but we will not help the Chinese Catholics if we continually demonize China, as some American media do, for reasons that are not only religious.