The story of the Good Samaritan shows the priest and the Levite passing by the wounded man. There is unconcern, lack of commitment and of compassion even among good people (Lk 10:30-35).

Let’s be honest. There is a ‘global cooling’ (as opposed to global warming) of human relationships in the world today. Some speak of the return of the ‘Ice Age’ due to a changed style of life and work: new technologies pinning our attention not on persons but on ‘things’; decline of the extended family; uprooting of communities; weakening of values; fragmentation of the mind and superficiality of interests in a market-dominated society; accelerated pace of life. Communications with each other have become hurried and impersonal. Profit and efficiency are considered more important than warmth and companionship. Relationships with family members and friends have turned matter-of-fact and businesslike.

In addition, there is a compassion fatigue arising out of growing indifference to human pain. Violence so dominates the news every day that we have become desensitized to human suffering. We are no more shocked even by the worst human tragedy. In such an atmosphere, it is difficult for us to maintain ourselves in compassion. We grow indifferent and insensitive. We harden our hearts. And this indifference creates a free space for violence to spread further: nation against nation, class against class, ethnic group against ethnic group, majority against minority, and vice versa. Violence may be in the name of religion, ethnicity, territory, human rights, or social justice. In his time, Buddha was shocked when he saw people going “along the banks of the Ganges striking, laying waste, mutilating and commanding others to mutilate, oppressing and commanding others to oppress” (Digha Nikaya 1,52).

In all these conflicts, the strong usually have their way. And those who feel that they are unjustly treated take to violence in response. In situations of tension, rather than become judgmental, shouldn’t aggrieved groups be heard to reduce their anger? Could we study the history of their specific grievances with sympathy and search for answers? Let us not leave people in anger, lest they be led into sin (Eph 4:26), says St. Paul. These are areas for ongoing dialogue, areas where we can collaborate with people of all traditions.

The Mission of Anger-Reduction

Jesus rebukes James and John for proposing to call down fire upon Samaria (Lk 9: 51-55).

Quarrels do happen in human life. But a compromise is possible. Even stubborn opponents can come together after a serious conflict and emerge from the vicious circle into which they have been caught: violence – counter violence – desperate response – violence in return. We need to help each other to compromise. Having worked for peace and reconciliation among conflicting groups during the last two decades, I know the meaning of ‘collective anger.’ I have seen it with my own eyes in contexts where hundreds of people had been killed and thousands of homes destroyed. In those contexts, I considered ‘anger-reduction’ as the first step towards peace negotiations. And I used to pray that we might become the lambs of God who take away the anger of the world! That is how we can bring the Compassion of God into diverse Asian contexts. What I said of local small situations would be true of international conflicts of major nature as well.

Working for anger-reduction has become a mission in itself. Centuries ago, Buddha had wisely said: “Never in this world will hatred cease by hatred…hatred is ceased by love.” It will only be after anger is reduced that we will succeed in bringing logic into discussion, good sense into conversation, persuasion into discussions, and fairness into conclusions. Many serious problems like regional and national conflicts, clash of economic interests, ethnic and ideological self-affirmation will call for higher levels of thought than those generated by the immediate circumstances. They invite deeper sense of justice and surer forms of mutual solidarity among the makers of the world today. Whether it be a small family quarrel or a major war involving many nations, the same rhythms and patterns are always visible; a pedagogy of persuasion is the only way forward. And it will involve a dialogue.

Forgiveness for Historic Injuries

Jesus is sorry for Jerusalem (Lk 13:34). He weeps over the city (Lk 19:41-44).

It can happen that anger accumulates over the years and is handed down from one generation to another: hurtful emotions connected with national humiliations, defeats, historic injuries received centuries ago, remain fresh in collective memory as though they happened only the other day. These are the negative assets, deficit capital of a society, of a religious community, ethnic group, and of sovereign states. And this type of buried anger can explode any day. Daily papers will tell you how much of unresolved resentment still remains on earth. If one nation forgives another, each ethnic or religious group or individual, forgives another wholeheartedly, what accumulated joy there would be in the world today! That would bring compassion into the streets, into byways and sidelanes into homes and into market places. All the accumulated energies spent on hate-filled ruminations and thoughts of revenge would be directed to life-saving and prosperity-promoting activities. Should not people of various religious traditions engage themselves in dialogue on these possibilities?

But let us look at the reality of the day. There is so much of unforgiveness. Unforgiving persons and communities are like a congested city. The roads are blocked; cars cannot move, garbage cannot be collected, people are immobilized. Rancor blocks vital energy and creative thought, and poisons life. If we learn to place ourselves in the position of our opponent and feel sympathy for his sufferings and dilemmas, we may begin to understand why he did what he did, and find it easier to forgive. Thus, instead of exploding into anger, we would find a way of explaining our own position in a constructive way, without hurting anyone at any stage. We would cease to feed on anger and shorten our lives. We would generate energy to take up other positive projects.

Rescuing the Compassion-Heritage in Asia

“The Lord turned around and looked straight at Peter, and Peter remembered… Peter went out and wept bitterly” (Lk 22:61-62).

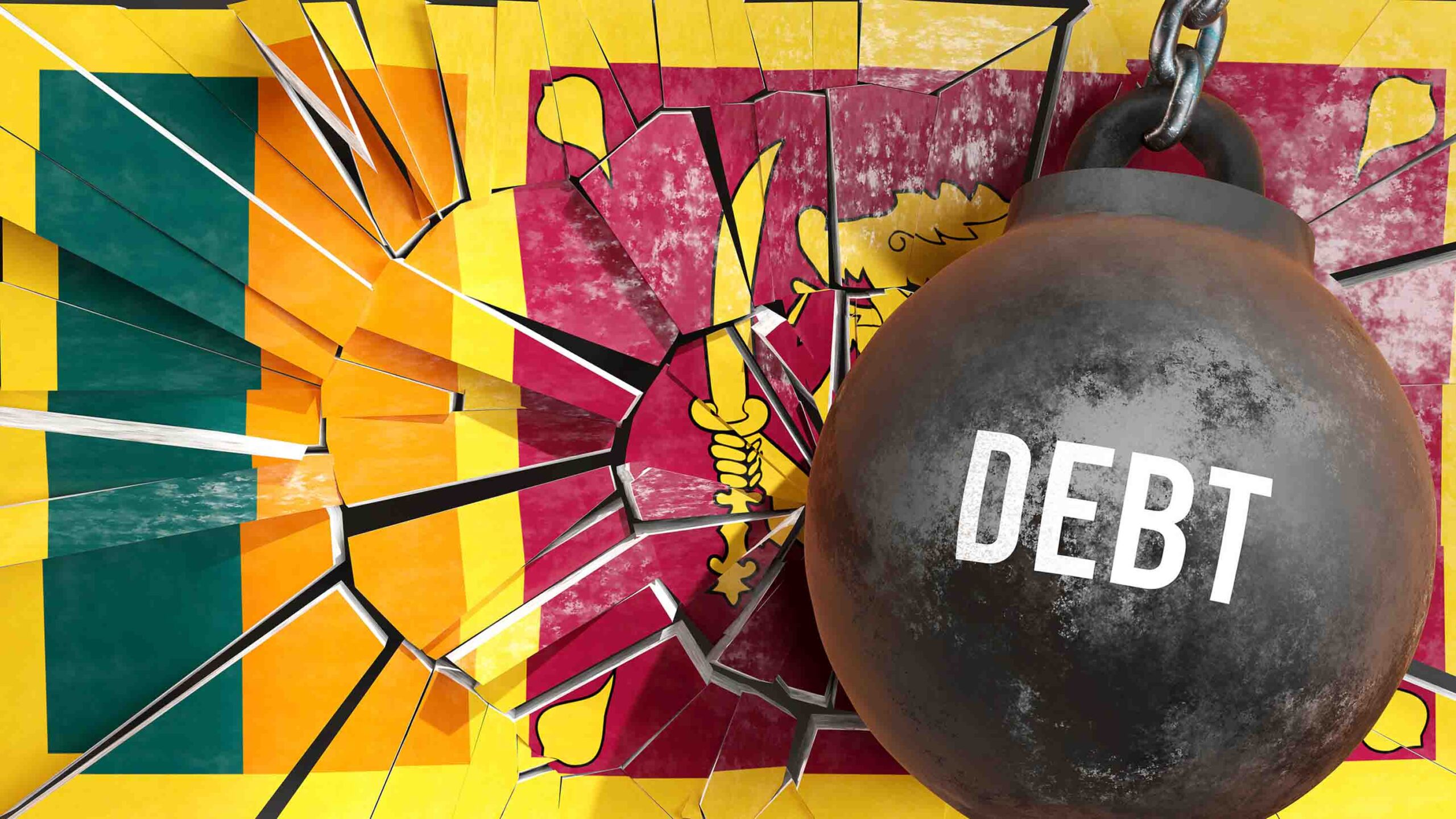

Today, we see that we run short of the compassion assets that were deeply rooted in our Asian cultures. Our cultural stamina gets exhausted all the more in our times because an economy-driven worldview has been fast eroding our indigenous cultures for years. That is what makes our society yield easily to temptations towards violence, corruption, damage to environment, and irresponsible governance. When we have allowed the market to define our identity and shape our destiny, we have made our cultures the prime victims; we have allowed the weakening of our social bonds, sense of common belonging, inherited traditions, and commitment to shared values and ideals, and the great stock of compassion we had in our traditions.

The time has come for us to stand aside and develop a detached view of things, withdraw for a while and reflect, move apart and weep, meditate, and pray. It is in this way that we build up our inner resources. Mahatma Gandhi said: “Such power as I possess for working in the political field has been derived from my experiments in the spiritual field.”

No wonder he conveyed his message as much, through religious silence, as by political creativity. We have to keep trying to unearth our buried stock of compassion in this difficult situation. These are areas for dialogue and mutual sharing of concerns.

Compassion AT the Highest Levels

“Settle the dispute with him before you get to court” (Lk 12:58).

Can we take compassion to the highest levels of political and economic planning: for example, to the situations of arms race between Asian countries, to border disputes, murderous competition? Is it possible to propose to people a strategy of completing and complementing each other’s role (in yin-yang manner), rather than confronting and crushing each other, humiliating each other? Someone will say these things at the global and national levels are far beyond me, I cannot do anything. But I can pray. I can take a compassionate view of things. By tempering my own perception of things with compassion, I am making that quality shape my own opinion. In a democracy, everyone’s opinion counts, whether spoken or written. Thus I can influence public opinion. In this manner, I can take compassion to the most unexpected places. I can set in motion an ongoing dialogue.

How can I take compassion to other places – like, the universities where ideas are generated, legislatures where policies are shaped, the media where information is shared, the market place where the livelihood of ordinary people is decided – always sparing a thought for the poor, the weak, the environment?

From Violence to Compassion

Jesus said, do good to your enemies. “For God is good to the ungrateful and the wicked. Be merciful just as your Father is merciful” (Lk 6:36).

There was a great emperor in India who did not believe in such pious things. History tells us, he led a mighty army against the Kalingas (Orissa) and killed 100,000 people and led a bigger number into exile. But then, the instinct for compassion, deeply rooted in every Asian heart, caught up with him. He was filled with deep remorse and was converted to a philosophy of non-violence (Ahimsa). His name was Asoka (269-232 BC).

He gave up his ambition to conquer the world by means of arms. He developed another strategy: one of conquest by dharma. He felt this manner of conquest would give satisfaction to the victors and the vanquished alike. He encouraged the spirit of happy relationships and dialogue among all religious groups and traditions in his empire. Gradually, he became a totally dedicated person. He wanted reports concerning the welfare of the people to be brought to him at all hours wherever he was, even if he were at his meals or in bed. “I consider it my only duty to promote the welfare of all men… There is verily no duty which is more important to me than promoting the welfare of all men” (Ashoka’s Rock Edict 6). It was Asoka who sent out Buddhist missionaries all over Asia.

Compassion Stirs Committed Service

The father of the prodigal son had pity on his son Lk 15:20-24).

Many link an attitude of nonviolence and compassion with timidity, passivity, inaction, non-commitment. The contrary is true. Mahatma Gandhi used to say: “Nonviolence is not a cover for cowardice; it is the supreme virtue of the brave. Exercise of nonviolence requires far greater bravery than that of swordsmanship. Cowardice is wholly inconsistent with nonviolence.”

In fact, this authoritative teacher of nonviolence was anything but a timid pacifist. “Gandhi was an unusual kind of pacifist….He was a demon of energy and action, a hustler, and a man who not only drives himself but drives others. He sent us to the villages, and the countryside hummed with the activity of innumerable messengers of the new gospel of action… thus, he effected a vast psychological revolution not only among those who followed his lead but also among his opponents and those many neutrals” (The Discovery of India). In him, there was no submission to fate but fearless resistance to evil, though peaceful and courteous.

Bringing Compassion or Leadership

“He has chosen Me to bring Good News to the poor….the time has come when the Lord will save His people” (Lk 4:18-19).

What Gandhi was doing was fully in keeping with the most ancient traditions of Asia. That is why he was able to command millions. Confucius used to say: “If you are kind, then you will be able to command others” (Analects 17.6). And the great Chinese teacher showed how he intended to be kind: “If even a simple peasant comes, in all sincerity, and asks me a question, I am ready to thresh the matter out, with all its pros and cons, to the very end” (Analects IX,7).

It is something admirable to have the capacity to understand other people’s feelings and their points of view and have empathy for them, even when we disagree. We need to step out of ourselves and enter into other people’s lives with understanding. That is compassion. That sort of relationships nourishes the life of communities. It is absolutely needed for promoting collaboration and preserving social cohesion.

Vivekananda, a Hindu reformer, used to say that the sole aim of his life was to stop mutual wrangling, to teach universal truths, to bring all people together, so that they might love one another and work in peace for their common good. In this sort of generosity, the giver himself becomes a beneficiary. The more the sage “gives to people, the more he has” (Tao Te Ching 81).

Compassion and Tender Love

“When you give a feast, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind” for, they cannot pay back (Lk 14:13-14). “Hurry out to the streets and alleys of the town, and bring back the poor, the crippled, the blind, and the lame” (Lk 14:21).

“All of us believe in compassion,” said the Dalai Lama; “but we needed a Mother Teresa to show us how.” She took the message of Jesus seriously: “Be compassionate as your Father is compassionate” (Lk 6:36). Love between adults is expressed through cordiality, warmth, respect for each other’s views, appreciation of achievements, esteem for each other’s culture, etc. But children need something more; they need tender affection, warmth, nearness, physical touch, intimate interaction. So do people who are seriously sick. Pope Francis seems to manifest an amazing ability to reach out to the very young and very old.

Similarly, people who are handicapped, poor, forgotten, despised, marginalized, are extremely happy to have someone who takes interest in them, talks to them familiarly, cares for them. They long for intimacy and affection as they see reflected in your eyes, voice, and handshake. They wish to be known, to be remembered, to have someone with whom they can share their deepest agonies. That is what made Mother Teresa say: “Suffering in the world is to teach me compassion.”

Curiously, recent researches show that people whose parents were warm, patient and affectionate have lower incidence of ulcers, alcoholism, heart disease; the opposite group manifested opposite conditions. A brief chat, a pat on the back, or a wave, these and such things are extremely powerful in creating a sense of belonging. In search of this sense of belonging, young people seek affiliation even in the most radical groups and armed outfits. These are issues over which an intelligent dialogue among people of diverse traditions would be useful.

Compassionate to Nature

Look at the wild flowers, lilies, ravens, wild grass; God looks after them (Lk 12:24-27).

Today, everybody will agree that compassion is due not only to our own fellow human beings; it is due to the rest of creation as well. Asian sages were highly sensitive to the needs of all living things and to all other elements in nature. In modern times, we have lost something of that sensitivity. The products of technology and supermarkets have made our life easier, faster, more efficient but also colder and harsher: harsher to cultures and traditions; harsher to life in its multiple forms, harsher to nature in its diverse existences. And, yet, our life depends on nature; we are nourished and nurtured by nature. Apart from it, we are reduced to nothing. All our impressive achievements are mere empty show. Theodore Roosevelt used to look at the stars and galaxies to remind himself how small he was even though he headed a mighty nation.

Centuries ago, Jain sages had taught: “A wise man should not act sinfully toward the earth, nor cause others to do so” (Jainism: Acaranga Sutra 50). “Reckless men who cut trees down for their pleasure destroy many living beings. By destroying plants… a careless man does harm to his own soul” (Jainism: Sutrakritanga I.7.9). The Psalmist says: “God has compassion on all He made” (Ps 145:9). Emperor Asoka forbade the destruction of forests.

The Muslim poet Iqbal sang: “All Nature, Oh my heart, is your fellow-creature.” And Tagore: “I asked the tree, speak to me about God. And it blossomed.”

Compassion towards nature is an area of most relevant dialogue in modern times.

Benefits of Compassion to Oneself

You do yourself a favor when you are kind (Prov 11:17).

The most convincing argument in favor of compassion is that the giver benefits most of all. His/her generosity is not a loss to him/her. He/she is the prime beneficiary. These words of Jesus are most moving: “Judge not, and you will not be judged; condemn not, and you will not be condemned; forgive, and you will be forgiven; give, and it will be given to you: good measure, pressed down, shaken together, running over, will be put on your lap. For the measure you give will be the measure you get back” (Lk 6:37-38). The Book of Proverbs says: “Be kind and honest and you will live a long life” (Prov 21:21).

Modern medical sciences confirm that this is true, that kind people are healthier and live longer, are more popular and productive, have greater success in business and lead happier lives, than others. This is because our thoughts influence each cell in our body, affect blood pressure and the blood flow, nourishing every organ and every faculty. You ought to remember more than anything else, you are internally so ‘designed’ as to be caring, empathic, and open to others. That is why you find it a pleasure to help and that is why your constitution benefits, because you are born to be kind and compassionate. You will sleep more easily and wake more cheerfully because you love people. People will love you; external dangers will not harm you. Your face will be radiant and mind, serene.

Pope Francis and his “Revolution of Tenderness”

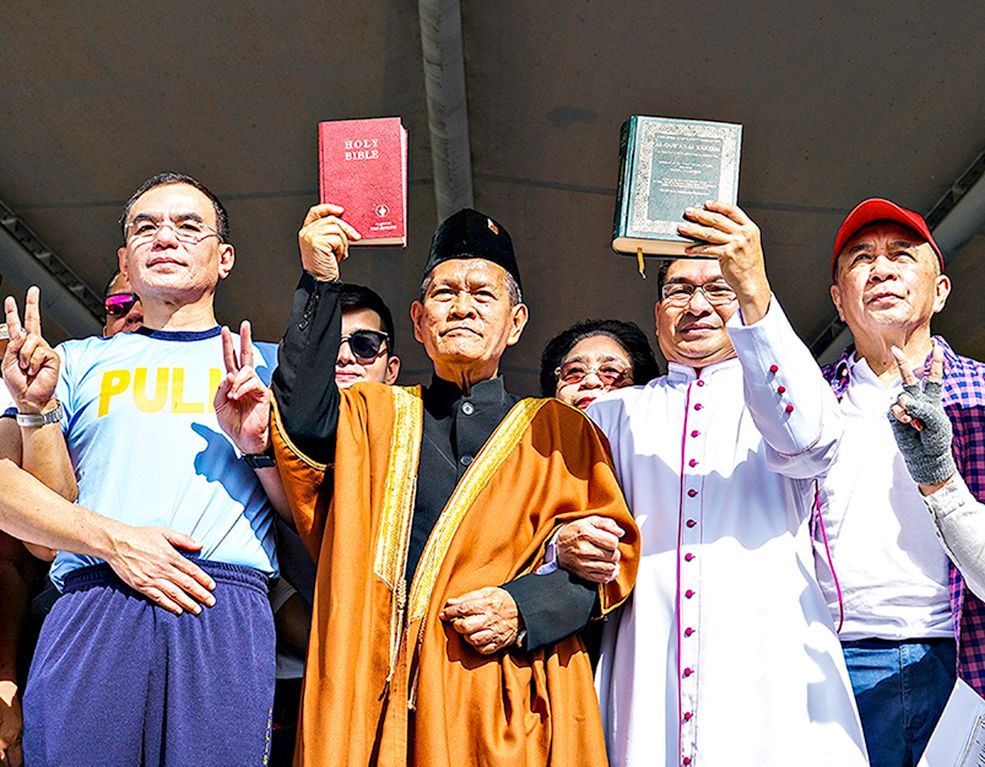

Amazingly, the thoughts of religious leaders of all persuasions seem to be converging. As we have seen above, several outstanding leaders of our times have been calling for compassion. So has Pope Francis been after he became the Bishop of Rome. In a recent message, he has called for a “Revolution of Tenderness.” He notices that, in today’s consumer society, the anguish that comes from a covetous heart and blunted conscience leaves no room for other people; there is no place for the poor.

The Pope realizes the need for continuous interrelationships. The world has become a smaller place, he says, and that has made constant interaction among people of different background necessary. The most serious problem in the world is not that resources are running short, but that we are finding coexistence difficult. He calls for respectful recognition of diversity and fostering of friendship among people of different faiths.

Pope Francis feels distressed that tensions arise along the lines of political and economic interests which get mixed up with cultural and religious differences and are further aggravated by misunderstandings and errors of the past. He describes the sharing of Jesus’ message as the building up of “authentic relationships.” People of various religious persuasions should come together in a struggle against the loss of spiritual values in a secularized society. It is precisely when one is firm in one’s own conviction that one becomes capable of understanding and respecting others.

Compassion for the Least Privileged

Whoever shows kindness to others should do it cheerfully (Rom 12:8).

Believers wish to be compassionate, most of all because they see God Himself in their brothers and sisters, especially in the least privileged among them. As they extol the Lord for His compassion, they promise to serve Him in their brethren, and they do so happily. It gives them enormous joy because the love of God has been poured into their hearts (Rom 5:5).

It is only by sharing our love with all in full, being affectionate in families, being committed to the welfare of society, generous to the poor, deeply involved in working for the common good, forgiving amidst tensions, shall we make God’s compassion true and real in our own surroundings. An Asian conversation on this theme will save the continent. And the fruit, thereof, will benefit the entire world!