The collection of “Our Lady’s Box” in the archives of the Shrine of Fatima in Portugal reveals the intricacies of many family problems or longings: children’s fears towards their parents or relatives; confession of their own or their father’s crimes; concern or sadness over dramatic situations.

“What I ask you most fervently is to bring my mother and father together;” and, above the sentence inscribed on a little sheet from a notebook, there are the words father and mother, written in big letters. “For my mother to get along with my father” or “for my father to accept me” are other such wishes.

The relationships between couples do not always go well: a letter from a Portuguese rural woman asks for her husband to return from Lisbon as she has no news from him. Another intercedes for the conversion of her “husband who lives in corruption, with prostitutes, convert him so that he returns to his sacred home;” a third woman wants “the grace for a man to get away from a prostitute woman with whom he lives,” and yet another wants a “spirit of justice” for her husband and to “take away his alcoholic addiction.”

The strict morality of the time–these letters were mostly written in the 1950s and 1960s, as we can read in the first article–imposed restrictions on one’s conscience and desired not to fall into “temptations,” an expression almost always referred to as immoral behavior: “That I may not have bad thoughts,” asks one letter writer.

“That I may not have such bad thoughts and not consent to them. I am 18 years old, a formidable age, but full of temptations. Help me and accompany me in my life always,” a Portuguese female student asked in May 1967.

Bad thoughts, in her own concept, was what a student in a religious school felt, at least during some days, in May 1964, when she wrote a little diary confessing her passion for one of the nuns: “I made the sacrifice, dominating myself to not let the fire inside me be seen–love for Mother P. I couldn’t go on without exploding.”

There are much more serious dramas socially tolerated at that time. In the tone of one who begs, ‘L.’ writes: “I earnestly beg you for purity of body and soul, Lady… How many times have I let my father touch me, not knowing that this act was impure… Make me more intimate and more confident with my mother… Convert my father and, if necessary, take away those vital sex forces from him if you see fit. Mother, you know that I am becoming a woman, I feel it well, you know that in the presence of advances from my father if you do not help me, I will fall into the incalculable mud and go to hell. Mother, do not allow that.”

Human Concerns

What one reads in these messages reflects, says Marco Daniel Duarte, “human concerns: on the one hand, thanksgiving because something in the life of the believer has happened, referring to a special grace granted through the Virgin of Fatima; on the other hand, specific requests for the concrete life of the believer, the family, the wider family that surrounds him, the wider community that can be a nation or a place that is at war and that is also the object of these requests, or even the planet itself.” Or even “requests concerning health, the social position that people have in the community, the way of being and living life, not only in the community but on a broader scale.”

“Knowing that someone cares about us gives a lot of tranquility, a lot of strength, a lot of courage,” states psychiatrist Luísa Gonçalves, who works in the national Armed Forces Hospital, in Lisbon. “Being loved, knowing that one is loved, gives courage, makes people strong, and transforms them because they feel that there is someone who cares, who remembers them, who wants them to succeed in life. Faith has that value too.”

If Our Lady of Fatima was not there, things could be serious in some situations: “Dear Mommy…you know that I only have you in this world and for me you are everything…Don’t abandon me. Don’t you see how lonely I feel? There are moments in which if it weren’t for you, I would have already ended my life.”

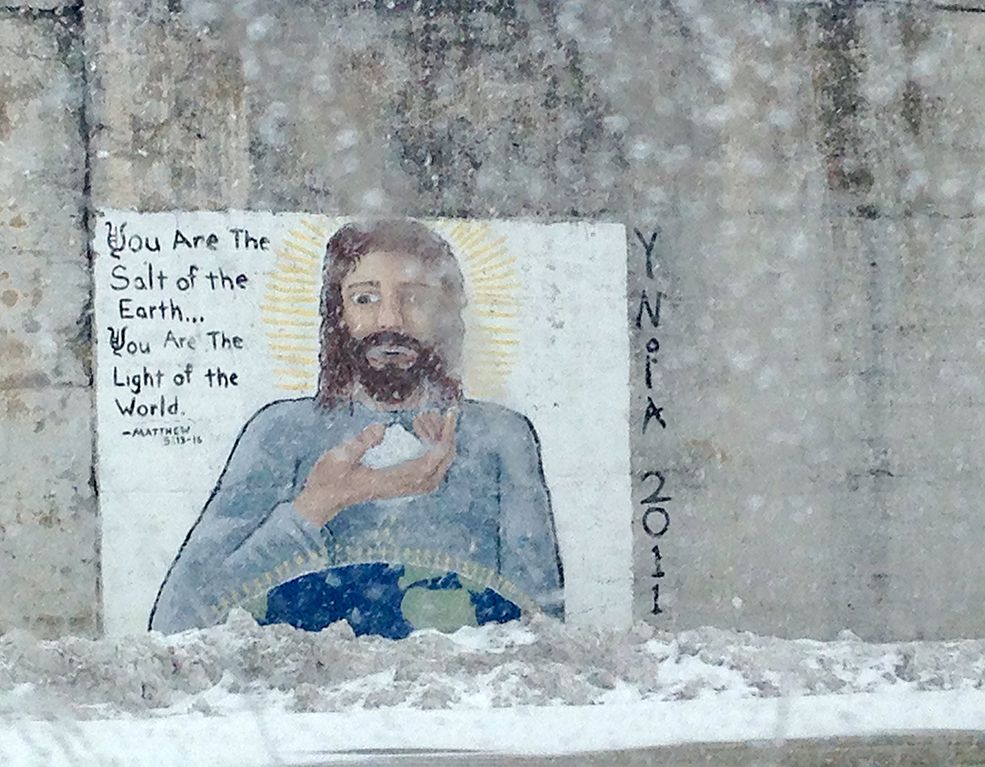

The archive is indeed full of mysteries, enigmas, and personal needs. But also, of course, spiritual needs and requests for peace. In May 1969, a message sent from Spain condenses in one sentence another of the main issues of the Fatima message and also of this archive: “To You, Mary of Peace, I beseech You to ask Your Son that there may be no wars.”

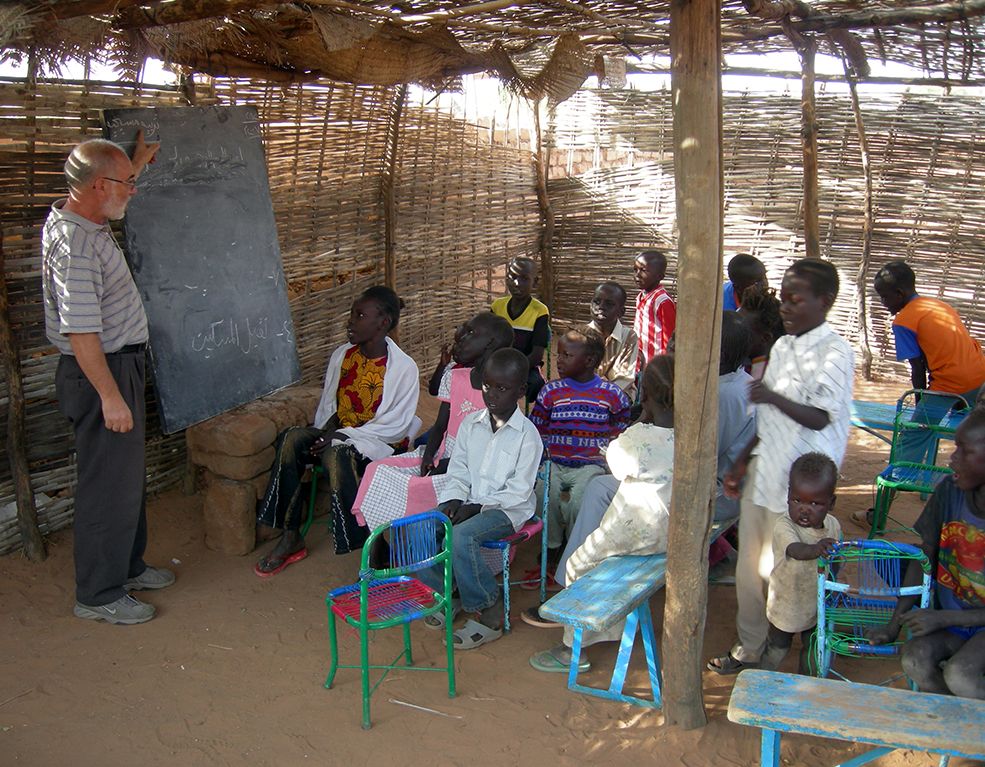

For letters coming from many foreign countries, including the Philippines, it is not possible to carry out such an in-depth analysis (the messages are dispersed in the file boxes and not grouped by country or language); in a random sample, it is clear that there are also people from lower and poor classes of the population with enough education to be able to express themselves.

For example, when J. writes, with spelling errors: “Maria Mother, I ask you in your presence for all my children and my husband, that we all love you with more strength and perseverance until the end of our days.”

A Universal Desire For Peace

From the very beginning, the desire for peace has been inscribed in the events of Fatima. On May 13, 1917, in her first dialogue during the apparition, the little seer Lúcia, then 10-years-old, recounts that she asked, “when will the war end?”

The desire is universal and generic requests abound, such as “Give peace to the world, let the war stop.” As written in two small cards from Spain: “Bring peace to the world,” says one of them from 1958, with an illegible signature. “My most loving Mother, give us peace in our home and the union of all and for peace in the world”, asks another.

The theme of war is apparent from an early period until the late 1980s, in the anti-communist dimension that the message of Fatima includes. In the former Soviet Union, Bolshevism and Stalinism made Christians and believers in general one of the privileged targets of persecution. Starting in the 1920s, millions of believers would be taken to the forced labor camps of the ‘Gulag archipelago.’

Between 1925 and 1946, while a Dorothean Sister and resident in Tuy and Pontevedra (Galicia, Spain), Lúcia would receive such news, which worsened with the religious tensions of the Second Spanish Republic and the Spanish Civil War.

All these reports shaped the references to the ‘conversion of Russia’ and to communism, which was seen by Lúcia and many Catholics as an enemy of the Christian faith. Communism comes to be seen by Lúcia (who later became a Carmelite nun) and many Catholics as an enemy of Christian civilization and of faith itself–whether in Russia, Portugal, Spain, the United Kingdom, Brazil, or the United States.

When World War II ends, Lúcia has no doubts in assigning the Portuguese dictator Oliveira Salazar an almost messianic role. In a letter addressed in 1945 to Cardinal Gonçalves Cerejeira, Patriarch of Lisbon, she wrote that Salazar is the person “chosen [by God] to continue to govern” Portugal.

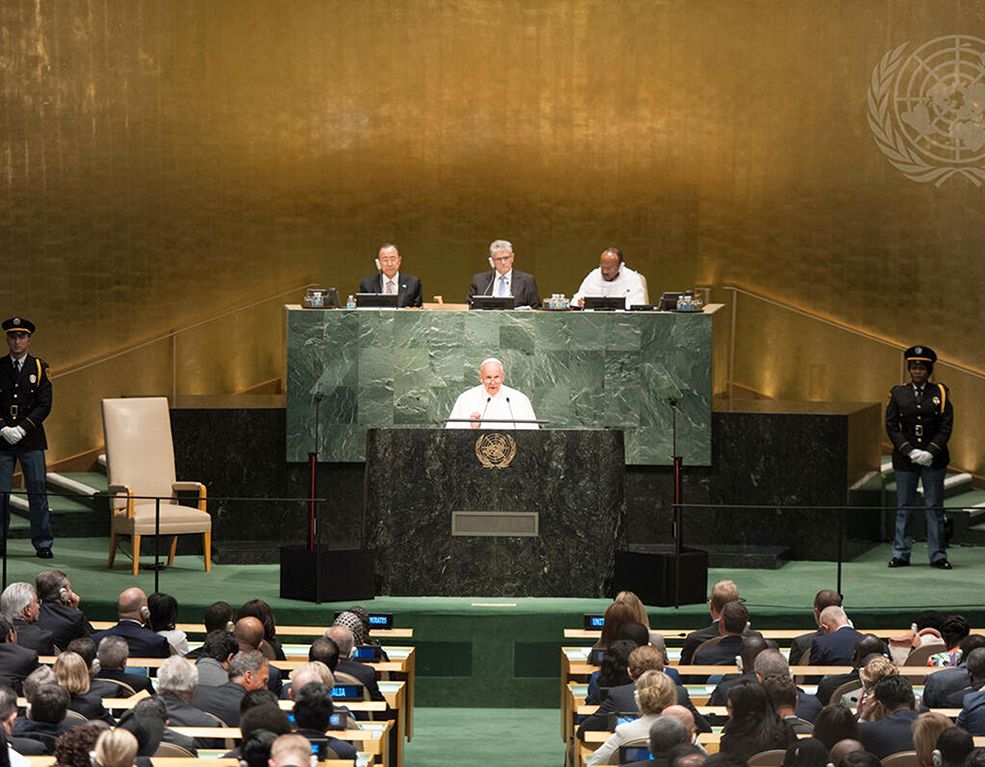

With the visit of Pope Paul VI, in 1967, 50 years after the events of Fatima, the priority in the official message is given to the theme of peace, which was in Lúcia’s first question in 1917. The visit causes discomfort for the Portuguese dictator and Paul VI will not fail to refer directly, several times, to the theme of peace, which was already a priority theme for several Catholic groups in opposition to the Portuguese dictatorship, which would only end on April 25, 1974.

Regarding the colonial war that Portugal was waging in Angola, a letter from a student in Lisbon summed it up, joining Portugal and Spain in the same design: “Lady of the Rosary of Fatima give peace in the world…make Russia convert, make there be peace in the world, make the soldiers not to suffer so much in Angola and in other countries. Lady of the Rosary save Portugal from a great war that will unfold and Portugal only has on its side our Spain that forms with us the little corner of the world.”