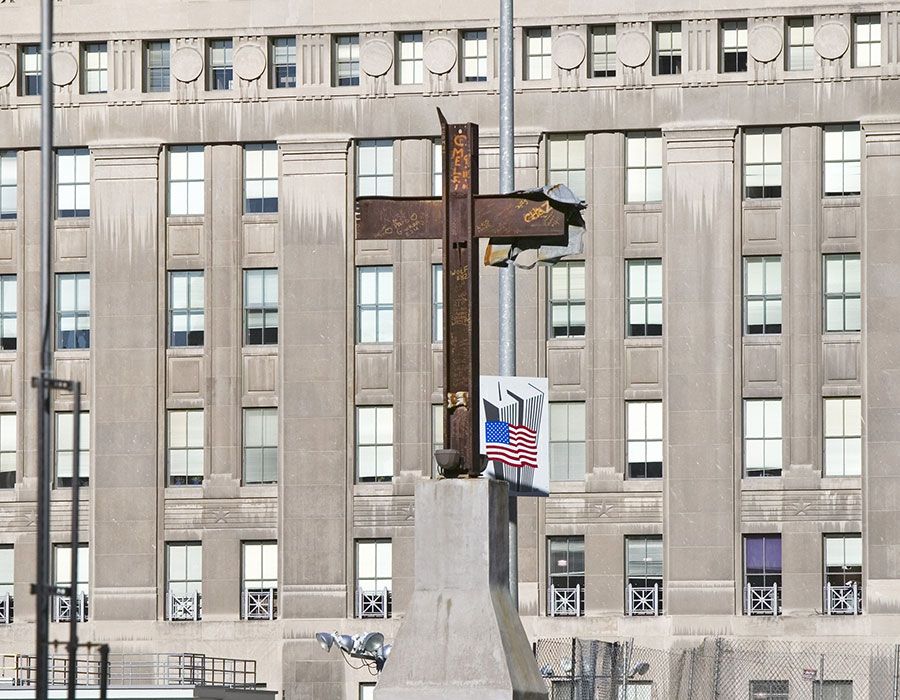

There is no doubt that of the 19 new blessed martyrs, the best known are the seven monks of Tibhirine. Responsible for this notoriety were “Of Gods and Men,” the movie by Xavier Bouvois which was a hit at the box-office, the circumstances of their kidnapping and successive tragic death, but also, and perhaps above all, the long and not yet exhausted polemic about who killed them. Their bodies were never found, only their heads which are now resting in the cemetery of the monastery of Tibhirine on the mountainside of the Atlas, some one hundred kilometers west of Algiers.

It is worthwhile to remember the context in which the religious men and women became victims of violence.

After the cancellation, in January 1992, of the second round of the legislative polls which would have given the Islamic Salvation Front (FSI) the parliamentary majority in order to found the Islamic State foreseen by the electoral program, the terrorist violence inspired by the fundamentalists, which was already present in the country, broke loose in Algeria.

The most numerous victims were not only the intellectuals and the journalists inclined to denounce violence, but also the common people and the religious leaders themselves. Among the victims there were also 99 imams who refused to justify the violence in the name of Islam.

Among the targets of those years, there were also the “misbelievers,” i.e. the non-Muslim foreigners, including the religious. In 1993 and at the beginning of 1994, Monsignor Teissier and Cardinal Léon-Etienne Duval, who, at the time of the Algeria liberation war (1954-1962), had spoken against torture and in favor of independence, were pointed out as “enemies” and possible targets.

In little more than two years, between 1994 and 1996, the foreign victims counted about a hundred, a trickle which has continued even if with less intensity up to the present time.

Serving The Humble

In the nineties, the Church was at the exclusive service of the Muslim population. The present blessed martyrs were people with a special relationship with the Algerian people: they were sharing with them conditions and problems.

In those years, some religious communities abandoned the most exposed places, while others withdrew all together. Those who remained were well aware of the danger. All the same they remained at the service of the most humble and needy people. The first two to fall, Fr. Henri Vergès and Sr. Paule-Hélène, were killed in May 1994 at the public library of one of the poorest areas of Algiers, where they were helping the youth in their studies. The following year, two sisters who were working in the formation of young women were also murdered in another popular area of the capital.

It is this profound relationship with the population that the terrorist were afraid of, since they did not conceive any possible political, social or cultural interaction. This dimension was at that time particularly visible among the monks who were completely immersed in the life of the little village of Tibhirine. There was the experience of Bro. Luc, the doctor who had been at the service of the village community for decades, extremely well known in the whole region, and who had been the protagonist, together with an Italian confrere, of a brief kidnapping during the liberation struggle.

At the basis of the conscious acceptance of the risks, there was a new idea of Christian presence in the Muslim context, well represented by the spiritual last will of Fr. Christian: “If it will happen one day that I fall victim of terrorism, I would like that my community, my Church and my family would remember that my life was consecrated to God and to this country.”

The same clear-mindedness and the same inspiration were proper of the Dominican Msgr. Pierre Claverie, who, born and grown up in Algiers, before becoming bishop of Orano in 1981, had multiple shared experiences with the Algerian populace. In his “Letter from Algeria” at the end of 1994, after having stated that “death can come from anywhere, at any moment and by anybody” he was reminding everybody that “we continue to share with the people the hard daily reality, in order to show our solidarity in suffering with those men and women who, like us, nurse the dream of another Algeria, reconciled within itself and with its past.” “We keep asking ourselves of the fact that perhaps we have not yet given enough proof of our disinterested will to be peace artisans, stripped of every willpower and feeling of superiority.”

Profound Friendship

The experiences and the writings of the 19 new blessed are precious pearls in order to understand the Muslim world; to overcome, notwithstanding the violence that has crushed them, the incrusted prejudices of a populist and xenophobic propaganda regarding Islam, and to conceive a possible life in common.

Tens of thousands of Algerians gathered around the martyrs’ death. At Bishop Pierre’s funeral, the cathedral of Orano was packed with Muslims. Every day the basilica of Our Lady of Africa that dominates the Algiers bay is visited by dozens of Muslim women. The very Tibhirine monastery is more and more visited by Algerians who find in those places part of the history of their country. From the 2016 summer, the monastery is once again firmly inhabited by a religious community, Chemin Nouf, still dealing with administrative problems.

Also because of this, the former “gardener” of Tibhirine, Fr. Jean-Marie Lassausse, who after the murder of the monks, had assured the presence and the continuity of the farm work, has launched, in the new book “Let us not forget Tibhirine,” the invitation to meditate on the profound links of friendship which have originated in that place.