Exploring this question may begin with the Advent 2020 Pastoral Statement of the Philippine bishops (CBCP), entitled “Becoming Jesus’ Missionary Disciples.” They wrote: “Five centuries ago, we received the marvelous gift of the Christian faith; our hearts overflow with joy and gratitude. Why, of all the nations and peoples in Asia, did God choose the Philippines to be among the first to receive this precious gift? The clear answer is this: God’s magnanimous, overflowing love.”

The bishops continue: “We recall what God told His people Israel regarding His choice: “It was not because you are the largest of all nations that the Lord set his heart on you and chose you, for you are the smallest of all nations. It was because the Lord loved you and because of his fidelity…” (Dt 7:7-8). Only God’s freely given love can illuminate the choice of the Filipino people to receive this valuable gift of faith!”

Dynamic Faith. “The Christian faith arrived and prospered in our land through the dedication and heroic sacrifices of thousands of men and women missionaries from various parts of the world. They treasured the gift of faith they had received and desired to share this gift with others. As the theme chosen by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) for this fifth centennial notes: all Christians are ‘gifted to give.’”

The CBCP Pastoral Statement continues: “This ‘giftedness’ motivated generous missionaries over the centuries; it must also enflame the hearts of all of us today to engage in mission here at home and in other countries (missio ad gentes). Indeed, this is part of Jesus’ mission mandate to his disciples: ‘What you have received as a gift, give as a gift’ (Mt 10:8). We pray for a missionary renewal of our Church—both at home (ad intra) and beyond our borders (ad extra) during our celebration of the 500 years—and into the future!”

Why Mission? What motivated the early missionaries who traveled great distances and endured many challenges and sufferings? Admittedly, they may have had mixed motives—practical, evangelical, strategic, and personal; yet, they spent their lives promoting the Christian faith among the diverse peoples they encountered. These missionaries sincerely sought to share their faith convictions with the local indigenous peoples.

Historically, it is known that in March 1521, Ferdinand Magellan arrived in search of spices and converts for Charles I (Emperor Charles V). His expedition was accompanied by Father Pedro de Valderrama, who celebrated the First Mass in the islands on Easter Sunday, March 31, 1521. Then, two weeks later, on April 14, Cebu Chieftain Datu Humabon and Queen Juana along with 800 locals, accepted baptism.

An organized evangelization program only began in 1565 with the Augustinians accompanying Legaspi’s expedition. Additional missionary groups soon followed: Franciscans (1578), Jesuits (1581), Dominicans (1587), and Augustinian Recollects (1606). Manila soon became a bishopric (1579) and an archbishopric (1595).

Evangelization proceeded under the Spanish system of the Patronato Real (royal patronage), an arrangement by which the Spanish crown gave financial support and protection to the Church in the Philippines while exercising considerable control over its decisions and activities. For example, the appointment of missionaries to a parish or mission station was subject to the governor’s approval as vice-patron. The Patronato system (a mixed blessing) ended in 1898 with the change of sovereignty from Spain to the United States.

Mission Methods. The Spanish missionaries employed a variety of approaches to evangelization. The scattered clan villages were gathered into larger communities (pueblos, cabeceras); this process implied radical lifestyle changes and thus was accomplished only gradually and with many difficulties.

Religious instruction was conducted using native languages (a truly wise decision), as few Filipinos outside the Intramuros area of Manila were ever able to use Spanish with any proficiency. In most missions, the primary schools supplied the new Christian communities with catechists and local officials.

Religion began to permeate society by substituting liturgical and paraliturgical observances (fiestas, processions, novenas) for the traditional rites and fiestas. This was another wise strategy. Notably, many of these elements are manifested in contemporary Filipino religiosity.

Social Justice Option. An important factor in the acceptance of the Christian faith by Filipinos was the social involvement of the Church. In addition to a wide variety of educational initiatives through schools and catechetical centers, the missionaries fostered various programs to promote physical health among the people better. Before the end of the sixteenth century, Manila had three hospitals (one for Spaniards, another for natives, and a third for the Chinese).

The Philippine Church of the sixteenth century certainly took sides, and it was not with the rich and powerful nor fellow Spaniards, but with those who were oppressed and victims of injustice. Philippine Church historian, John N. Schumacher, SJ, notes: “Skeptics have often questioned the reality of the rapid conversion of sixteenth-century Filipinos. If one wishes the answer, it is to be found here, that the Church as a whole took the side of the poor and the oppressed, whether the oppressors were Spaniards or Filipino principales.”

These historical facts bring to mind the emphasis that Pope Francis places on God’s mercy in the Church’s mission in his 2015 Misericordiae Vultus (The Face of Mercy). The pope asserts: “The Church is commissioned to announce the mercy of God, the beating heart of the Gospel…. As the Church is charged with the task of the new evangelization, the theme of mercy must be proposed repeatedly with new enthusiasm…. In our parishes, communities, associations, and movements, in a word, wherever there are Christians, everyone should find an oasis of mercy” (MV 12).

Serious Shortcoming. Catholicism had taken permanent root in the Philippines as the people’s religion by the eighteenth century, if not earlier. However, one major weakness was the retarded development of the native clergy. The unsatisfactory results of the early experiments in Latin America made Spanish missionaries extremely cautious in admitting native candidates to the priesthood. Native Filipinos started getting ordained in the late seventeenth century.

Some bishops were increasingly eager for a diocesan clergy completely under their jurisdiction. Tragically, Archbishop Sancho de Santa Justa y Rufina of Manila (1767-1787) ordained natives even when they lacked the necessary aptitude, training, and character; the results proved disastrous on several levels. Some improvement in formation and an increase in vocations occurred after the arrival of the Vincentians (1862), who took charge of diocesan seminaries.

Becoming a Vatican II Church. The Second Vatican Council (1962-65) promoted a significant ecclesial paradigm shift in theologies, values, and pastoral practices. This pivotal Church event was attended by fifty persons from the Philippines (49 bishops and one layman). Two-thirds of the participant-bishops were Filipinos; one-third were expatriate missionary bishops, mainly serving in remote areas of Luzon and Mindanao.

Received enthusiastically in the Philippines, Vatican II prompted the bishops to launch programs of evangelization on many levels; the social apostolate was among its strong emphases. The bishops issued several pastoral letters on social action, justice, and development. Early renewal efforts centered on forming and supporting unions and cooperatives for farmers, laborers, and fishermen.

A major local Church milestone was achieved in the Second Plenary Council of the Philippines (PCP-II) of 1991; the number of active participants reached nearly 500! PCP-II addressed seven major areas: Christian Life, Religious Concerns, Social Concerns, Church and Society, Laity, Religious, and Clergy. Succinctly stated, PCP-II helped concretize the aggiornamento renewal of Vatican II on numerous levels within the Philippine context.

Continuing Renewal. Undoubtedly, the Vatican II ecclesiology has taken root in the Philippine Church! Important strengths include the following: the inductive approach of theology, an enculturated social teaching, a spirituality of human development, renewed ecclesiology and missiology, committed service to many Filipinos facing diverse dehumanizing social ills, an engagement in social issues in a non-partisan but active manner, and a commitment to creating structures of participation in Church and society.

These many strengths coalesce to produce a truly missionary local Church. This reality is a cause for rejoicing—as the fifth centenary of the arrival of Christianity is gratefully celebrated!

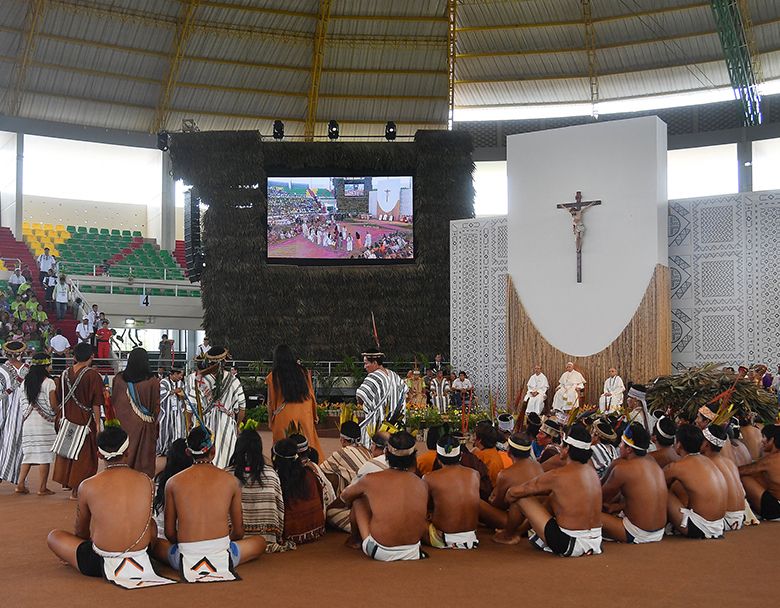

Encouraging Words. Filipinos have a genuine love and respect for Pope Francis, especially following his January 2015 pastoral visit, which emphasized the theme of mercy and compassion. They cling to his encouraging advice and humble actions.

Pope Francis’ words spoken at the 2023 World Youth Day resonate deeply with all local Catholics: “This is not the time to stop or give up…. Now is the God-given time of grace to sail boldly into the sea of evangelization and of mission.”

James H. Kroeger, MM, has served mission in Asia (Philippines and Bangladesh) for over five decades. He recently completed Walking with Pope Francis: The Official Documents in Everyday Language, a synthesis-popularization of ten of Pope Francis’ pivotal documents from 2013-2022; it is available from Orbis Books in New York and the Pauline Sisters in Manila and Nairobi.