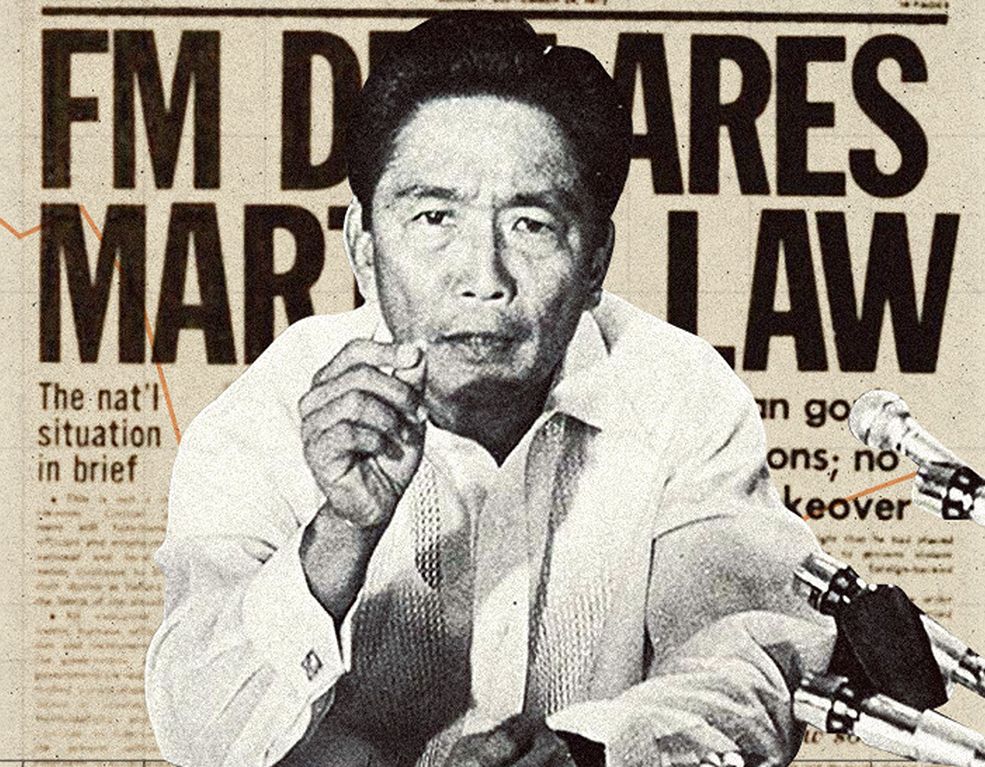

Marcos was elected president in 1965. From 1965 to 1971, the year before Martial Law was declared, the economic growth of the Philippines, as reflected by its gross domestic product (GDP), ranged from 5.27 percent to 5.43 percent. It was in 1973 and 1976 when GDP hit 8.92 percent and 8.81 percent respectively, which Marcos’ son and namesake, Bongbong, claim as proof of his father’s achievements. But he skipped the part when some of the Philippines’ worst recessions also took place under his father’s dictatorship.

In 1984 and 1985, the first two years after the murder of Senator Benigno Aquino Jr, the Philippine GDP contracted to negative 7.32 percent and negative 7.04 percent respectively.

The Philippines’ GDP from 1965 to 1986, based on data from the World Bank and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, went down from 4.43 percent (1966) to 3.417 percent (1986). Professor Emmanuel de Dios of the University of the Philippines’ School of Economics said this was the reason the record of Marcos should not be viewed in morsels of good numbers.

Recession

“You have to take the entire period,” De Dios told ABS-CBN News in 2017. “You did experience high growth in the early years, but you also experienced the worst recession in latter years,” he said. The Martial Law Museum likewise said that from $0.36 billion in 1961, the external debt of the Philippines “skyrocketed” to $28.26 billion in 1986. It said the increase in “our debts explains the growth, especially in infrastructure, primarily touted by some to assess the economic gains of the Marcos regime.”

“A debt-driven growth is a growth that sacrifices long-term benefits for short-term gratification, and ultimately leads to more burden than a boon for the future generations that must pay these debts,” the Martial Law Museum said. It likewise said that because “power was in the wrong hands,” the declaration of Martial Law and the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus “opened the real possibility of the violation of civil rights.” The writ, which in Latin refers to “having the body,” is a protection against illegal imprisonment.

Crackdown On Media

The media, extremely essential for any democracy, were likewise silenced by the dictatorship. “By shutting down competing voices and setting up a media outlet that was under his control, Marcos silenced public criticism and controlled the information that the people had access to,” the Martial Law Museum said. “By doing so, Marcos had the final say in whatever passed for the truth,” it added. Marcos lost no time enforcing the crackdown on media. On Sept. 18, 1972, he issued a Letter of Instruction No. 1 allowing the military to take over media, mainly ABS-CBN and Channel 5.

Some news outlets were allowed to operate, especially those that were owned by Marcos’ friends like Roberto Benedicto of the Kanlaon Broadcasting System and the Philippine Daily Express.

According to the Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission (HRVVMC), 579 businesses were likewise “violently and illegally” taken over by the dictatorship.

The Martial Law Museum said “poverty worsened” throughout the dictatorship, emphasizing that six out of 10 families were poor by the time the Marcos regime ended, an increase from the four out of 10 families before Marcos took office in 1965.

The daily income of agricultural workers declined by at least 30 percent–from P42 in 1962 to P30 in 1986. The wages of farmers even went as low as P23 in 1974, right after the declaration of Martial Law. From P127 and P89 daily income for skilled workers and workers without school training in 1962, wages fell sharply to P35 and P23 in 1986.

These declines happened in the years when prices of goods were surging especially in the last 10 years of the dictatorship. “We can see that prices of basic commodities tripled, such that what cost P100 in 1976 now cost more than P300–even nearing P400–in 1986,” said the Martial Law Museum.

Fleeing

After the EDSA People Power, a revolt that ended the more than the 20-year reign of the Marcoses reports documenting the family’s flight and arrival in Hawaii of crates of belongings, worth billions of pesos, were transported, too. The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, in the report “The End of an Era–Handholding Ferdinand Marcos in Exile,” said the United States Customs found 24 crates with gold bricks and diamond jewelry.

“Certificates for gold bullion valued in the billions of dollars were allegedly among the personal properties he, his family, his cronies, and business partners surreptitiously took with them when the US provided them safe passage to Hawaii,” the report said.

This narrative was strengthened when Marcos’ close confidante, the late industrialist Enrique Zobel, submitted a 14-page affidavit to the Senate blue ribbon committee. A report by ABS-CBN News said the dictator left his family–widow Imelda and children Bongbong, Imee and Irene–with $35 billion worth of gold bars in 1989. In reports by international newspapers The Guardian and Washington Post, it was said that the Marcoses carried with them essential belongings, including cash and gems (some of which were in diaper boxes), 70 pairs of jeweled cufflinks, and enough clothes to fill 67 racks.

Billions Stolen

The World Bank and UN Office on Drugs and Crimes said Marcos, having the longest reign as a dictator, stole between $5 billion and $10 billion from the country’s coffers. The corruption was so outrageous that it earned the distinction of being “The Greatest Robbery of a Government” from the Guinness Book of World Records.

On Dec. 21, 1990, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court decided that the dictator and his family hid $356 million in Swiss banks. The Philippine Supreme Court, in 2003, allowed the forfeiture of the finances in favor of the government of the Philippines.

In 2018, the anti-graft court Sandiganbayan convicted the dictator’s widow of seven counts of graft related to private foundations established in Switzerland while she was a government official from 1978 to 1984. She was sentenced to imprisonment of six years and one month to 11 years for each count, but she has served none after posting bail worth P300,000.

The Presidential Commission on Good Government, an office created by the late former President Corazon Aquino to go after the ill-gotten wealth of the Marcoses and their cronies, said in 2018 that P171 billion has already been recovered.

Human Rights Violations

The dictatorship was deadly, especially for those who stood against Marcos who were either killed or went missing. According to HRVVMC, 11,103 individuals had fallen victims to rights violations by the dictatorship. The count, however, covered only those with approved claims for compensation from the Human Rights Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013.

Amnesty International (AI) said there were 107,200 victims, mostly killed, tortured, and imprisoned by the Marcos regime. HRVVMC data showed that 2,326 were either killed or disappeared, never to be found. AI said at least 3,200 innocent people were killed.

The Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearance said that from 1971 to 1986, at least 878 people went missing and are now considered as disappeared. HRVVMC said there were 699 and 1,417 approved claims for those victims of illegal detention during the Marcos dictatorship. But AI counted at least 70,000 people who were wrongly imprisoned by the Marcos regime. Published in Inquirer.net