On September 9, 1980, Fr. Daniel Berrigan, his brother Fr. Philip, and six others (the “Plowshares Eight”) began the Plowshares Movement. They trespassed onto the General Electric nuclear missile facility in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, where they hammered on an unarmed nuclear weapon, a warhead nose cone, and poured blood onto documents and files: it was the first Plowshares action. They were arrested and charged with over ten different felony and misdemeanor counts. They were condemned to ten years in prison.

In his courtroom testimony at the Plowshares trial, Fr. Daniel described his daily confrontation with death as he accompanied the dying at St. Rose Cancer Home in New York City. He said the Plowshares action was connected with this ministry of facing death and struggling against it. He added that, in 1984, he had begun working at St. Vincent’s Hospital, New York City, where he ministered to men and women with H.I.V.-AIDS.

“It’s terrible for me to live in a time where I have nothing to say to human beings except, ‘Stop killing,’” he explained at the Plowshares trial. “There are other beautiful things that I would love to be saying to people.” On April 10, 1990, after ten years of appeals, the Berrigan’s group was re-sentenced and paroled for up to 23 and a half months in consideration of time already served in prison.

Slow move to pacifism

Daniel Berrigan was born in Virginia, Minnesota, in 1921. His father Thomas was a second-generation Irish Catholic. His mother Frieda Fromhart, of German descent, would feed any hungry itinerant who would come to the door during the Great Depression. Daniel was the fifth of six sons. His brother, fellow peace activist Philip Berrigan, was the youngest. Although his father had left the Church, Daniel remained attracted to the Catholic faith.

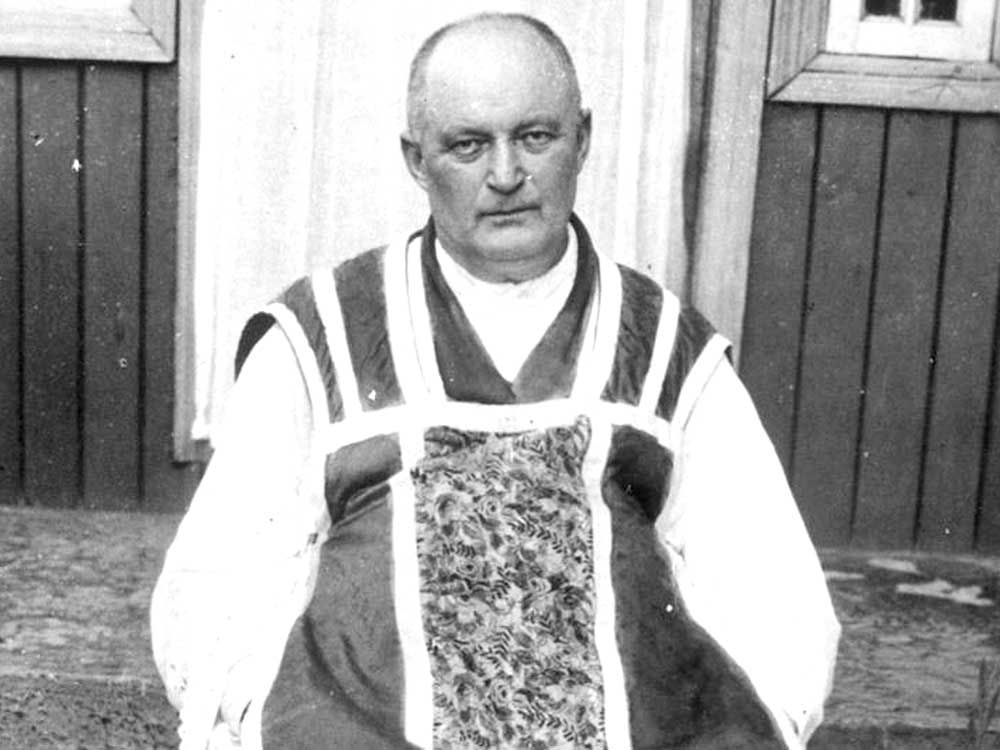

At age 5, Berrigan’s family moved to Syracuse, New York. In 1946, Daniel earned a bachelor’s degree from St. Andrew-on-Hudson, a Jesuit seminary in Hyde Park, New York. He was devoted to the Catholic Church throughout his youth. He joined the Jesuits directly out of high school in 1939 and was ordained to the priesthood in 1952. In that same year, he received a master’s degree from Woodstock College in Baltimore, Maryland.

During his regency period, Daniel taught at St. Peter’s Preparatory School in Jersey City from 1946 to 1949. While busy teaching, he also brought students across the Hudson to introduce them to the Catholic Worker (a newspaper published by the Catholic Worker Movement that was started by Dorothy Day to make people aware of church teaching on social justice). They often attended the “clarification of thought” meetings on Friday evenings, when speakers addressed topics of importance to the young Catholic movement. There, he met Dorothy Day.

“Dorothy Day taught me more than all the theologians,” Fr. Daniel told friends in 2008. “She awakened me to connections I had not thought of or been instructed in–the equation of human misery and poverty with war-making. She had a basic hope that God created the world with enough for everyone, but there was not enough for everyone.”

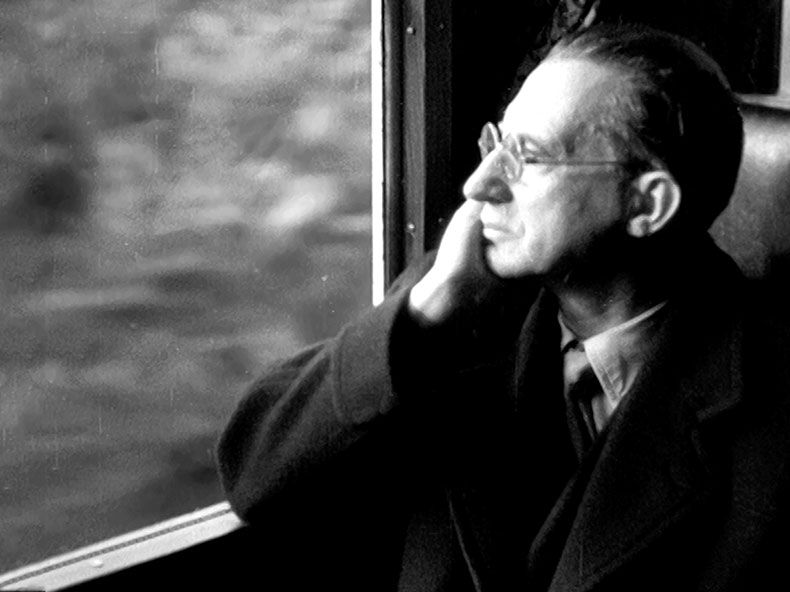

Later on, he was enriched by his contact with Thomas Merton. He regularly corresponded with Thomas Merton and also made annual trips to the Abbey of Gethsemani, Merton’s home, to give talks to the Trappist novices. In Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander (1966), Merton described Fr. Daniel Berrigan as “an altogether winning and warm intelligence and a man who, I think, has more than anyone I have ever met the true wide-ranging and simple heart of the Jesuit: zeal, compassion, understanding, and uninhibited religious freedom. Just seeing him restores one’s hope in the Church.”

After 1954, Fr. Daniel was assigned to teach theology and New Testament studies at different Jesuit schools in and around New York. The same year, he won the Lamont Prize for his book of poems, Time Without Number. He developed a reputation as a religious radical, working actively against poverty and on changing the relationship between priests and lay people. While on a sabbatical in 1963, he traveled to Paris and met French Jesuits who criticized the social and political conditions in Indochina. Taking inspiration from this, he and his brother Fr. Philip founded the Catholic Peace Fellowship, a group which organized protests against the war in Vietnam.

The Tet Offensive

In January 1968 came the hinge on which the Vietnam War turned: the Tet offensive. Eighty thousand North Vietnamese soldiers stormed out of the jungles, wreaking havoc on cities throughout South Vietnam, endangering even the U.S. Embassy in Saigon. Claimed as an American victory, Tet showed irrefutably that the United States had vastly undercounted the enemy it faced. Tet sparked a savage renewal of U.S. bombing of North Vietnam.

As it happened, a pair of American peace activists arrived in Hanoi just then, on a mission to receive from the North Vietnamese three freed prisoners of war. The activists were the historian Howard Zinn and Fr.Daniel Berrigan. He and Zinn spent their first night in Hanoi in an underground shelter while U.S. bombs fell from the sky – “under the rain of fire,” as Fr. Berrigan later described it. That night, and on subsequent nights, they huddled in shelters with, especially, children, who for Fr. Daniel obliterated from then on any capacity he might have had to cloak the realities of the war in abstraction. This episode led to his book Night Flight to Hanoi: War Diary with 11 Poems, published that December.

His poem “Children in the Shelter” marks his transformation: “I picked up the littlest/ a boy, his face/ breaded with rice (His sister calmly feeding him/as we climbed down)/ In my arms, fathered/ in a moment’s grace, the messiah/ of all my tears. I bore, reborn/ a Hiroshima child from hell.”

The saga of the two brothers

Fr. Daniel was deeply influenced by his younger brother Fr. Philip, who served in the army during World War II and, after the war, became a Josephine priest. Fr. Daniel marched with Fr. Philip in the civil rights movement at Selma in 1965. As Fr. Philip became more active in the anti–war movements against U.S. involvement in Vietnam in the late 1960s, Fr. Daniel joined him in the protests.

Their most famous protest was in 1968. With seven other participants, Frs. Daniel and Philip, using home-made napalm, burned 378 files of young men who were to be drafted for military service. This led to the Berrigans’ arrest with the other members of their group. For a time Frs. Daniel and Philip avoided their prison dates and were on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List. Eventually, Fr. Daniel served two years in prison and was released in 1972.

This group, which came to be known as the Catonville Nine, issued a statement after the incident: “We confront the Roman Catholic Church, other Christian bodies, and the synagogues of America with their silence and cowardice in the face of our country’s crimes. We are convinced that the religious bureaucracy in this country is racist, is an accomplice in this war, and is hostile to the poor.”

Fr. Daniel said in a statement: “Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children, the angering of the orderlies in the front parlor of the charnel house. We could not, so help us God, do otherwise.” Fr. Daniel Berrigan wrote of the incident and the trial in his play “The Trial of the Catonsville Nine.”

In retrospect, the trial of the Catonsville Nine was significant because it altered the resistance to the Vietnam War, moving activists from street protests to repeated acts of civil disobedience, including the burning of draft cards. As The New York Times noted in its obituary: Fr. Berrigan’s actions helped “shape the tactics of opposition to the Vietnam War.”

Fr. Daniel was fond of quoting a line from his brother Fr. Philip, that “if enough Christians follow the Gospel, they can bring any state to its knees.” At various points, he opposed U.S. military involvement in Central America, the two U.S.-led Gulf Wars, and the war in Kosovo. Despite his image as a radical leftist, Fr. Daniel Berrigan was also an outspoken opponent of abortion.

During a 1984 talk at a Catholic parish in the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, Fr. Daniel denounced what he called a “theory of allowable murder” in contemporary society. Christians should have no part in “abortion, war, paying taxes for war, or disposing of people on death row or warehousing the aged,” Fr. Daniel said on that occasion. “One cannot be pro-life and against a nuclear freeze”, he insisted, “or be a peace activist and defend abortion.”

“I know that this prophetic vision is not popular today in some spiritual circles,” Fr. Daniel said in a 2012 interview. “But our task is not to be popular or to be seen as having an impact but to speak the deepest truths that we know. We need to live our lives in accord with the deepest truths we know, even if doing so does not produce immediate results in the world.” Fr. Berrigan’s brother, Philip, died in 2002 at the age of 79.

This was written of the Berrigan brothers in Fr. Daniel’s obituary: “The American Jesuit priest Father Daniel Berrigan, who has recently died, formed a radical partnership with his younger brother Philip, that energized the movement against the Vietnam War in the 1960s and created a tradition of pacifist activism that lasted a generation. Unlike Philip, a former Josephite who gave up the priesthood and married an ex-nun, Daniel remained in holy orders as a Jesuit thinker, writer and teacher, and a well-regarded poet. If Philip was the heart of the anti-war movement, Daniel’s intellectual and theological contributions made him the brains.”

Berrigan’s Legacy

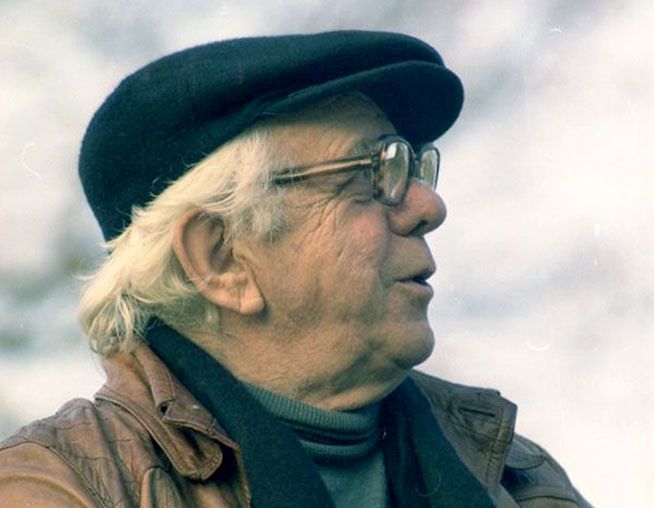

Even as an octogenarian, Fr. Daniel continued to protest, turning his attention to the U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the prison in Guantánamo Bay and the Occupy Wall Street movement. Friends remember him as courageous and creative in love, a person of integrity who was willing to pay the price, a beacon of hope and a sensitive and caring friend.

“I owe him my heart, my life and vocation,” Bill Wylie-Kellermann, pastor of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Detroit, writes of Fr. Daniel Berrigan. “In a century, how many souls on this sweet and beset old planet has Berrigan called to life in the Gospel? How many deeds of resurrection? How many hearts so indebted?”

Fr. Daniel Berrigan died in New York on April 30. He was 94 years of age. Almost contemporarily, a large representation of Catholic pacifists gathered in Rome and asked Pope Francis to write an encyclical letter condemning the theory of the “Just War.” A leader among them was Fr. John Dear, himself a Jesuit, who continues the legacy of Fr. Daniel Berrigan, fighting for the total abolition of war in international relations.