The 19th century industrial revolution caused the social question regarding the exploitation of the urban masses. Karl Marx and the communist movement were the first to acknowledge the impact of the social question. Their success was possible only because Christians were slow in understanding that the new social problems needed a new approach. The preaching of the Church was still based only on the principle that the rich had to come to the help of the poor out of charity.

But in the second part of the 19th century, the social teaching of the Church developed enormously and Catholic movements started organizing the workers in trade unions in order to fight for a new social order. This social movement on the part of Christians was encouraged by Pope Leo XIII with his encyclical Rerum Novarum (The New Things), 1891, which applied the Christian principles of the Gospel to the new social condition.

The Pope condemned the materialistic and revolutionary ideas of communism and, at the same time, the liberal ideas. He said that work is not a commodity to be put on the market, but it is connected with the dignity of the human person. He spoke of just salaries, decent working hours, regulations and right of the workers to organize themselves in trade unions.

He spoke of the social function of private property and of the duty of the state to bring about social laws and reforms in order to bring equality and harmony among different social classes. Behind this watershed document, there was the contribution of a Catholic economist who had made the solution of the social question his mission: Prof. Joseph Toniolo.

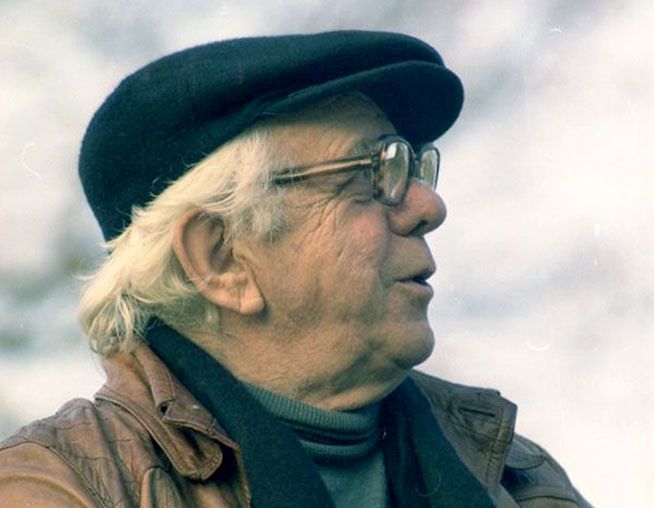

Professor and Family Man

Joseph Toniolo was born in Treviso on 7 March 1845 as the first of four children to Antonio Toniolo and Isabella Alessandrini. During his childhood the Toniolos moved several times since his father, an engineer, took different jobs at various places in the Veneto region. He attended high school at Saint Catherine’s school in Venice before entering Padua University. It was there that he studied law, but his father’s sudden death interrupted his studies though he later resumed his education and graduated.

Toniolo married Maria Schiratti and they had seven children. Rather than pursue a legal career, he taught economics for more than four decades, the last three at Pisa University. In 1889 he founded the Catholic Union for Social Studies and later started the International Review of Social Sciences in 1893.

Antonio Toniolo advocated worker protection and in 1889 organized a union to fight for workers’ rights. He said that economics “is an integral part of the operative design of God” which is considered to be an “obligation of justice” that should serve as an essential service to all people rather than a select few.

Professor Toniolo died on October 7, 1918 and his remains lie buried in the Santa Maria Assunta Church at Pieve di Soligo. He was beatified in Rome’s Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls on April 29, 2012.

Forerunner of Vatican II

Toniolo was an early Catholic advocate of labor unions, the fight against child labor and exploitation of workers, mandatory days off work, just wages and access to credit, and a number of other social reforms.

On the level of theory, Toniolo advocated a form of what is known as “corporatism,” a vision with historical roots in the guild system of medieval Italy. In practice, Toniolo placed emphasis on intermediary institutions standing between the individual and the state – the family, professional groups, voluntary associations, unions, and so on.

He saw these intermediary bodies as the best expression of what Catholic social thought would later come to call “subsidiarity,” meaning not substituting centralized authority for what can better be handled at lower levels, or privately.

Politically speaking, Toniolo parted company with both the dominant trends of his time: laissez-faire capitalism as articulated by Adam Smith, and state-centered socialism as advocated by Karl Mark. He insisted that classic capitalism rested on a false anthropology of individualism and egoism, while Marxism centered on a false idolatry of the state.

Many observers regard him as a forerunner of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) and its vision of the laity as the primary agents in the transformation of the secular world.

Champion of The Laity

In a message dispatched to a symposium organized to celebrate the memory of Toniolo, Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, the then Vatican Secretary of State, underlined his importance as a model of lay activism.

“In every historical moment there were pioneers who gave a new impulse and vigor to the Gospel’s perennial message of salvation,” Bertone said. “In the first millennium it was predominantly the monks, and in the second it was the mendicant orders. In the third, I’m convinced it will be principally the laity, as the witness of Joseph Toniolo demonstrates.”

Italian Minister Lorenzo Ornaghi compared Toniolo to English Cardinal John Henry Newman, another towering figure of 19th century Catholicism, in the sense that both men “offered the motives for a reasonable faith to those who believe, and laid the basis for friendship with those who don’t.”