An international conference on John Bradburne was held at the Universitá per Stranieri (University for Foreign Students) of Perugia, Italy, on March 30, 2017. It was a multinational occasion, with speakers from Italy, France, Spain, South Africa, and the U.K., and an attendance that included academics from several university departments, as well as representatives of the Catholic Church in Italy. Many university students were also present, testifying to the way the story of John Bradburne still appeals to young people.

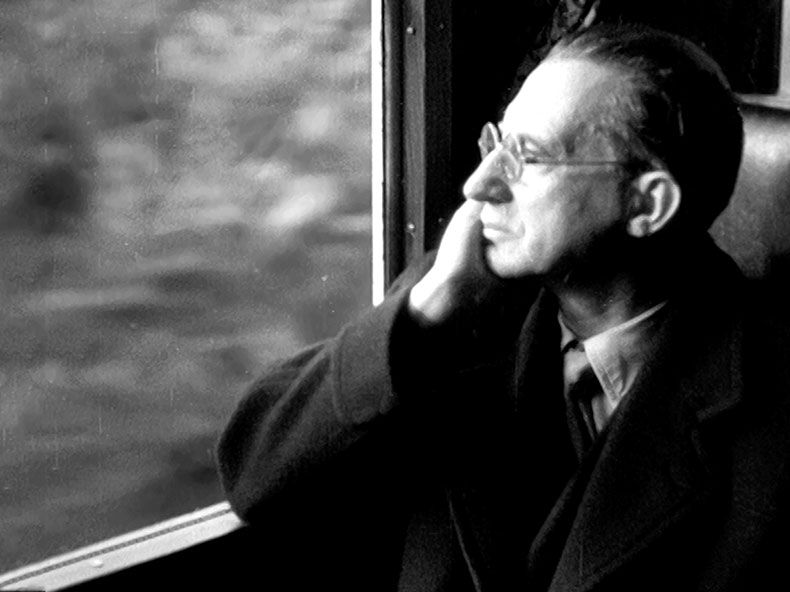

The idea for such an event arose in 2015, during an academic visit to Perugia by Professor David Crystal, the editor of Bradburne’s poetry. The motivation was to make John Bradburne’s writings available to a wider audience in Italy and elsewhere through the medium of translation. Perugia seemed to be the obvious location, for it is close to Assisi – places through which John Bradburne walked on his several journeys around Italy, and which he often refers to in his writing.

Although the cause of beatification of John Bradburne was not part of the remit of the conference, a groundswell of opinion emerged to that purpose. The outcome was the ‘Perugia Statement’, which was signed by many of the participants. It reads as follows: “As speakers and attendees at this conference, we firmly believe that the cause for his canonization should proceed at the earliest opportunity, especially in the light of his role as a model for young people, the poor and marginalized, and the care of those with devastating diseases.” Further support for the move came from Cardinal Gualtiero Bassetti, Archbishop of Perugia and now secretary of the Italian Episcopal Conference.

A cave where to pray

John Randal Bradburne was born in 1921 in Skirwith, Cumbria, England. His father, an Anglican clergyman, was the Rector of Skirwith at that time. John was educated at Gresham’s, an independent school in Norfolk, England, from 1934 to 1939. He was planning to continue his studies at a University when World War II began and he went straight to join the army.

John was assigned to the 9th Gurkha Rifles of the Indian Army in 1940. He soon found himself with them in Malaya to face the invasion of the Imperial Japanese Army. After the fall of Singapore, John spent a month in the jungle. With another Gurkha officer, he tried to sail a sampan to Sumatra but they were shipwrecked. A second attempt was successful, and John was rescued by a Royal Navy destroyer and returned to Dehra Dun. For his escape, he was awarded the Military Cross.

John Bradburne had a religious experience in Malaya, and the adventurer became the pilgrim. When he returned to England after the war, he stayed with the Benedictines at Buckfast Abbey, where he became a Roman Catholic in 1947. He wanted to be a Benedictine monk but, after a while, he felt a strong urge to travel.

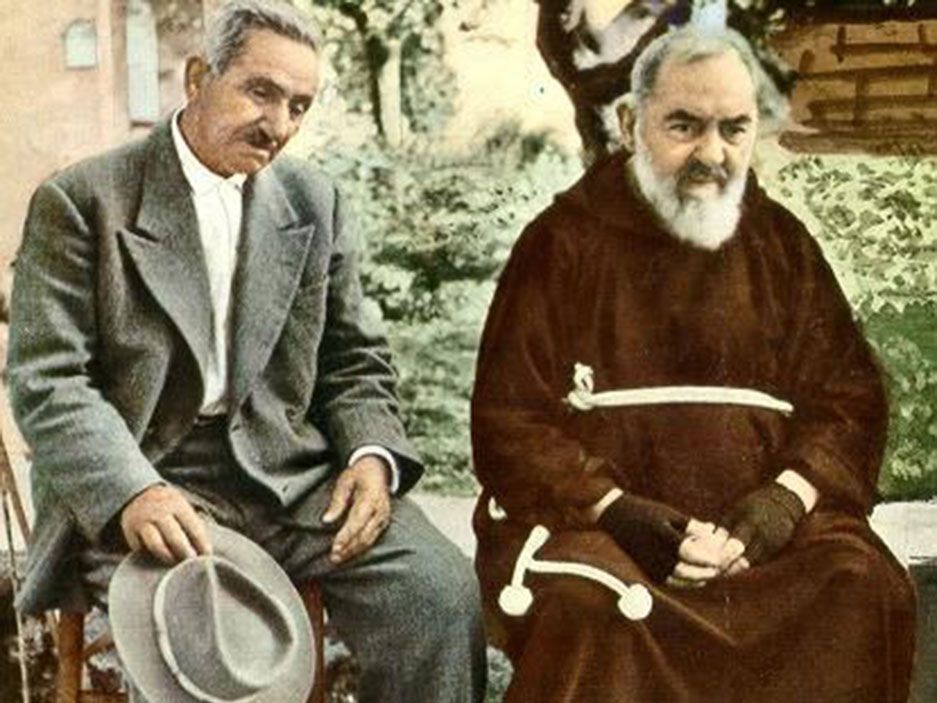

For the next sixteen years, John wandered through England, France, Italy, Greece and the Middle East with only a Gladstone bag as his companion. In England, he stayed with the Carthusians for seven months. After that, he walked to Rome and lived for a year in the organ loft of the small Church in a mountain village, playing the organ. Along the way, in 1956, on Good Friday, he joined the Secular Franciscan Order but he remained a layman.

John’s wanderlust came to an end in 1962, when he wrote to a Jesuit friend in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), who was his old Gurkha comrade. He asked, “Is there a cave in Africa where I can pray?” The answer was the invitation to come to Rhodesia and be a missionary helper. He came and helped in different capacities.

Eventually, in 1969, the Jesuit missionaries introduced him to the Mutemwa Leprosy Settlement near Mutoko, 143 kilometers northwest of Salisbury (now Harare). The 80 lepers were appallingly neglected, dirty and hungry, with the roofs of their little tin huts falling in. John immediately decided to stay with them, and never left until his death.

The guardian bees

John lived among the lepers, driving out the rats that gnawed them, cutting the nails of those who had fingers and toes, attending to them when they died. He helped build their small church, organizing its music, even teaching the lepers Latin for the Gregorian plainchant.

After a time, Bradburne fell out with the Leprosy Association that, in theory, ran Mutemwa. He hated the fact that it wanted the lepers to be known only by numbers. He refused to do this. He gave each leper a name, and wrote a poem about everyone. He was reprimanded for “being extravagant” because he insisted that each leper should have at least one loaf of bread a week.

He was expelled from the colony, so he went to live in a tent on the mountain above Mutemwa. There a farmer gave him a tin hut, with no electricity or water, just outside the perimeter fence. For the remaining six years of his life, John stayed there, and continued to minister as best he could. When not attending to the lepers, he lived the life of a hermit, eating very little, writing poetry and praying, often walking a prayer path on the hill.

As a lay member of the Third Order of St Francis, he obeyed its rule, singing the daily office of Our Lady. He lived its hours, rising at dawn for Matins and ending the day with Vespers and Compline. This discipline provided the context for many of the poems he wrote at the turning points of the day.

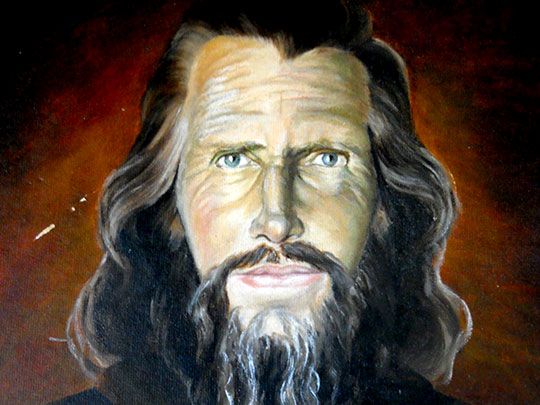

Though John was basically sociable, he did at time relish his solitude, resenting visits and interruptions. He allowed a swarm of wild African bees to nest in his hut, under his desk. They never bothered him, but certainly discouraged all but the most determined visitors. By now gone was the clean-cut military appearance. He looked somewhat wild, with long hair and beard framing his careworn countenance. His gaze was direct, unswerving, unsmiling, but his eyes still patient and gentle.

Three wishes

By July 1979, the Rhodesian Bush War, then in its 15th and last year, was approaching Mutemwa. John was urged by his friends to leave but he insisted that he should stay with the lepers. On Sunday, September 2, 1979, the guerrillas came for him. They took him into the bush and subjected him to mockery in front of a crowd, offering him girls to sleep with, trying to make him dance and even eat excrement.

The next day, their leaders interrogated him. John said little, but knelt and prayed. The guerrillas had local reports that the man was harmless, but they became fearful that, because of his abduction, he now knew too much. Eventually, they marched him out of the bush to the main road. There a guerrilla shot him. His half-naked body was left by the roadside.

After his arrival in Africa, John Bradburne had told a Franciscan priest that he had three wishes: to help the victims of leprosy, to die a martyr, and to be buried in the Franciscan habit. The first two had been fulfilled.

During his Requiem Mass, eye-witnesses saw a small pool of blood under the coffin. The undertaker was worried, thinking that there was an improper preparation of the body. After the mass, the coffin was reopened, but no sign of blood was found inside. It was, however, noticed that John had not been clothed in his Franciscan habit. His third wish was then fulfilled and he was clothed in it. The mystery of the blood has never been explained other than it being a miraculous event.