Presents, discusses and draws readers to reflect on issues of outmost relevance to the world today.

Very often, mission is carried out in frontier situations around the world. Those who embrace these situations have much to share.

Writer Ilsa Reyes will be exploring the richness of Pope Francis’s latest encyclical Fratelli Tutti with a view of helping our readers to get a grasp of the this beautiful papal document.

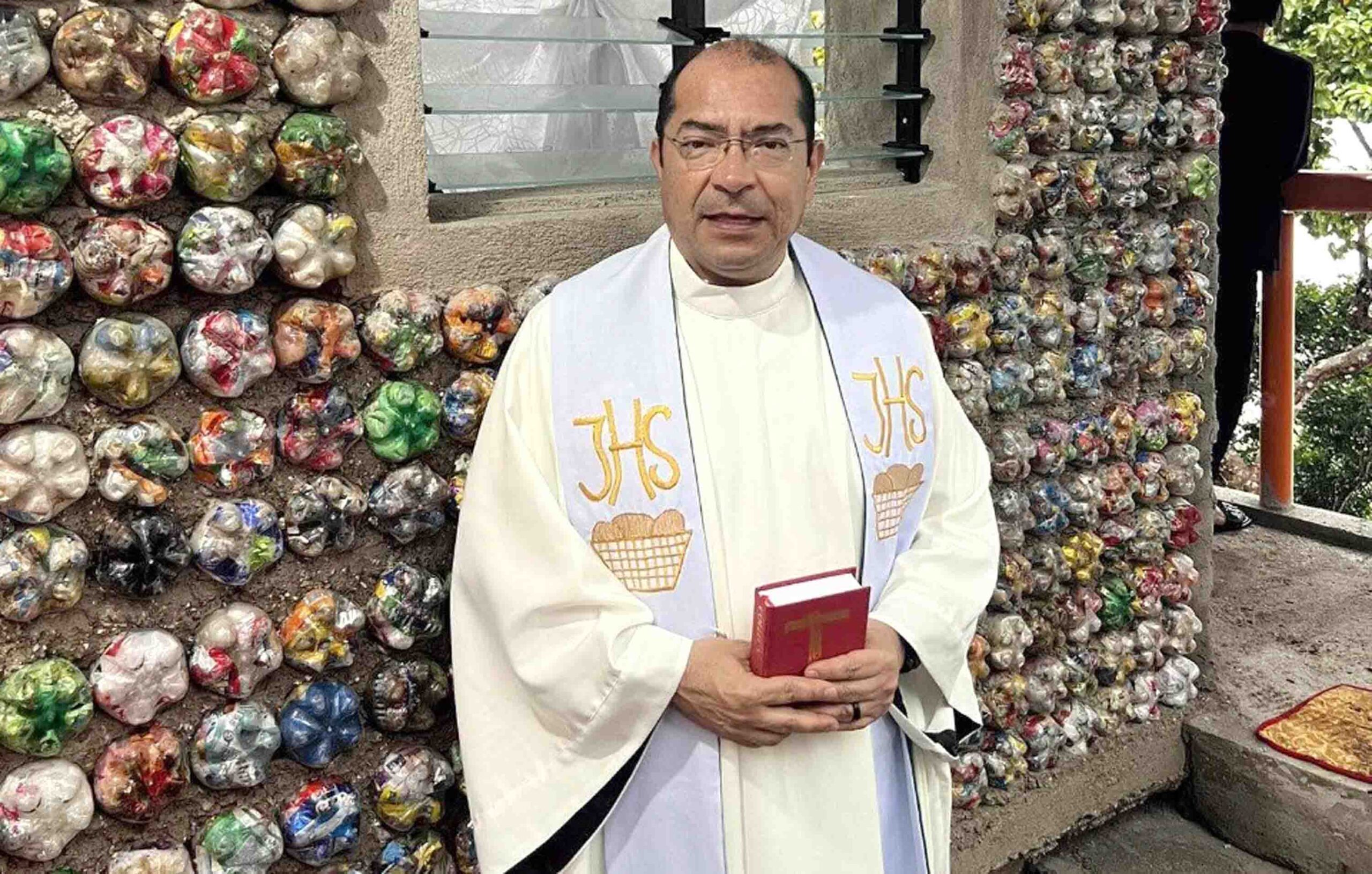

Puts to the front committed and inspiring people around the world who embrace humanitarian and religious causes with altruism and passion.

Focus on a given theme of interest touching upon social, economic and religious issues.

As the Philippines prepares to celebrate 500 years of the arrival of Christianity. Fr. James Kroeger leads us in this series into a discovery journey of the landmark events in the history of faith in the Philippine archipelago.

Aims to nurture and inspire our hearts and minds while pondering upon timely themes.

The large archipelago of the Philippines, in its richness of peoples and cultures, offers varied and challenging situations for mission.

Reflections and vocation stories that shape up the lives of young people.

As humor and goodness of heart are qualities of Christian and missionary life, the new column “Mission is fun” will be publishing some anecdotes and stories that have happened in a missionary context to lighten up the spirits and trigger a smile in our faces.

To help readers of World Mission live this year dedicated to Ecumenism, Interreligious Dialogue and Indigenous Peoples, Tita Puangco, writer and lecturer, shares in this section insights on the spirituality of communion.

A historic view of the Catholic movements that emerged from the grassroots as an inspiration by the Holy Spirit.

On the Year of Ecumenism, Interreligious Dialogue and Indigenous Peoples, radio host and communicator Ilsa Reyes, in her monthly column, encourages Christians and people of good will to be one with their fellow people of other sects, religions and tribes.

Questions to a personality of the Church or secular world on matters of interest that touch upon the

lives of people.

News from the Church, the missionary world and environment that inform and form the consciences.

A feature on environmental issues that are affecting the whole world with the view of raising awareness and prompting action.

The editor gives his personal take on a given topic related to the life of the Church, the society or the

world.

A monthly column on themes touching the lives of young people in the Year of the Youth in the Philippines by radio host and communicator I lsa Reyes.

A missionary living in the Chinese world shares his life-experiences made up of challenges and joyous encounters with common people.

Life stories of people who deserve to be known for who they were, what they did and what they stood for in their journey on earth.

Stories of people whom a missionary met in his life and who were touched by Jesus in mysterious ways.

Critical reflection from a Christian perspective on current issues.

Comboni missionary Fr. Lorenzo Carraro makes a journey through history pinpointing landmark events that changed the course of humanity.

A biographical sketch of a public person, known for his/her influence in the society and in the Church, showing an exemplary commitment to the service of others.

Gives fresh, truthful, and comprehensive information on issues that are of concern to all.

A column aimed at helping the readers live their Christian mission by focusing on what is essential in life and what it entails.

Peoples, events, religion, culture and the society of Asia in focus.

The human heart always searches for greatness in God’s eyes, treading the path to the fullness of life - no matter what it takes.

The subcontinent of India with its richness and variety of cultures and religions is given center stage.

The African continent in focus where Christianity is growing the fastest in the world.

Well-known writer and public speaker, Fr. Jerry Orbos, accompanies our journey of life and faith with moments of wit and inspiration based on the biblical and human wisdom.

On the year dedicated to St. Ignatius of Loyala, Fr. Lorenzo Carraro walks us through the main themes of the Ignatian spirituality.

Fr. John Taneburgo helps us to meditate every month on each of the Seven Last Words that Jesus uttered from the cross.

In this section, Fr. Lorenzo delves into the secrets and depths of the Sacred Scriptures opening for us the treasures of the Sacred Book so that the reader may delight in the knowledge of the Word of God.

Reflections about the synodal journey on a conversational and informal style to trigger reflection and sharing about the synodal path the Church has embarked upon.

This 'mini-course' series provides a comprehensive exploration of Vatican II, tracing its origins, key moments, and transformative impact on the Catholic Church.

This series offers an in-depth look at the Comboni Missionaries in Asia, highlighting their communities, apostolates, and the unique priorities guiding their mission. The articles provide insights into the challenges, triumphs, and the enduring values that define the Comboni presence in Asia.

Following the Synod on Synodality, this series examines how dioceses, parishes, and lay organizations in the Philippines are interpreting and applying the principles of the synod, the challenges encountered, and the diverse voices shaping the synodal journey toward a renewed Church.

This series introduces the Fathers of the Church, featuring the most prominent figures from the early centuries of Christianity. Each article explores the lives, teachings, and enduring influence of these foundational thinkers, highlighting their contributions the spiritual heritage of the Church.

In preparation for the 2025 Jubilee Year under the theme “Pilgrims of Hope,” 2024 has been designated a Year of Prayer. World Mission (courtesy of Aleteia) publishes every month a prayer by a saint to help our readers grow in the spirit of prayer in preparation for the Jubilee Year.

In Our World, the author explores the main trends shaping contemporary humanity from a critical and ethical perspective. Each article examines pressing issues such as technological advancement, environmental crises, social justice, and shifting cultural values, inviting readers to reflect on the moral implications and challenges of our rapidly changing world.

This series unpacks the principles of Catholic Social Doctrine, offering a deep dive into the Church's teachings on social justice, human dignity, and the common good.

Hopeful Living’ is the new section for 2026, authored by Fr. James Kroeger, who dedicated most of his missionary life to the Philippines. In this monthly contribution, he will explore various aspects of the virtue of hope. His aim is to help readers align their Christian lives more closely with a hopeful outlook.

Filipino Catholic scholar Jose Bautista writes each month about how the Philippines is at a crossroads, considering the recent flood control issues and other corruption scandals that have engulfed the nation. He incorporates the Church’s response and its moral perspective regarding these social challenges.

Test your knowledge and deepen your understanding with our Bible Quiz! Each quiz offers fun and challenging questions that explore key stories, themes, and figures from both the Old and New Testaments.