Sr. Stella Matutina of the Order of St. Benedict has her fair share of harassment because of her missionary work across Southern Philippines. In 2009, she woke up in Cateel, Davao Oriental with guns pointed at her. The nun was arrested and detained, together with anti-mining advocates, for educating and mobilizing tribal communities against mining. Matutina was even tagged as a member of the insurgent New Peoples’ Army and, just recently, was sued along with tribal leaders, children’s rights advocates and human rights defenders for allegedly kidnapping and trafficking lumad folks who evacuated to Davao City.

“They are not happy when we organize people and inform them of the negative and positive sides of mining. They even call me a fake nun to discredit what I am doing,” said Matutina, who is this year’s recipient of the Weimar Award for Human Rights, a prestigious citation conferred by the Weimar City Council in Germany, established in 1995.

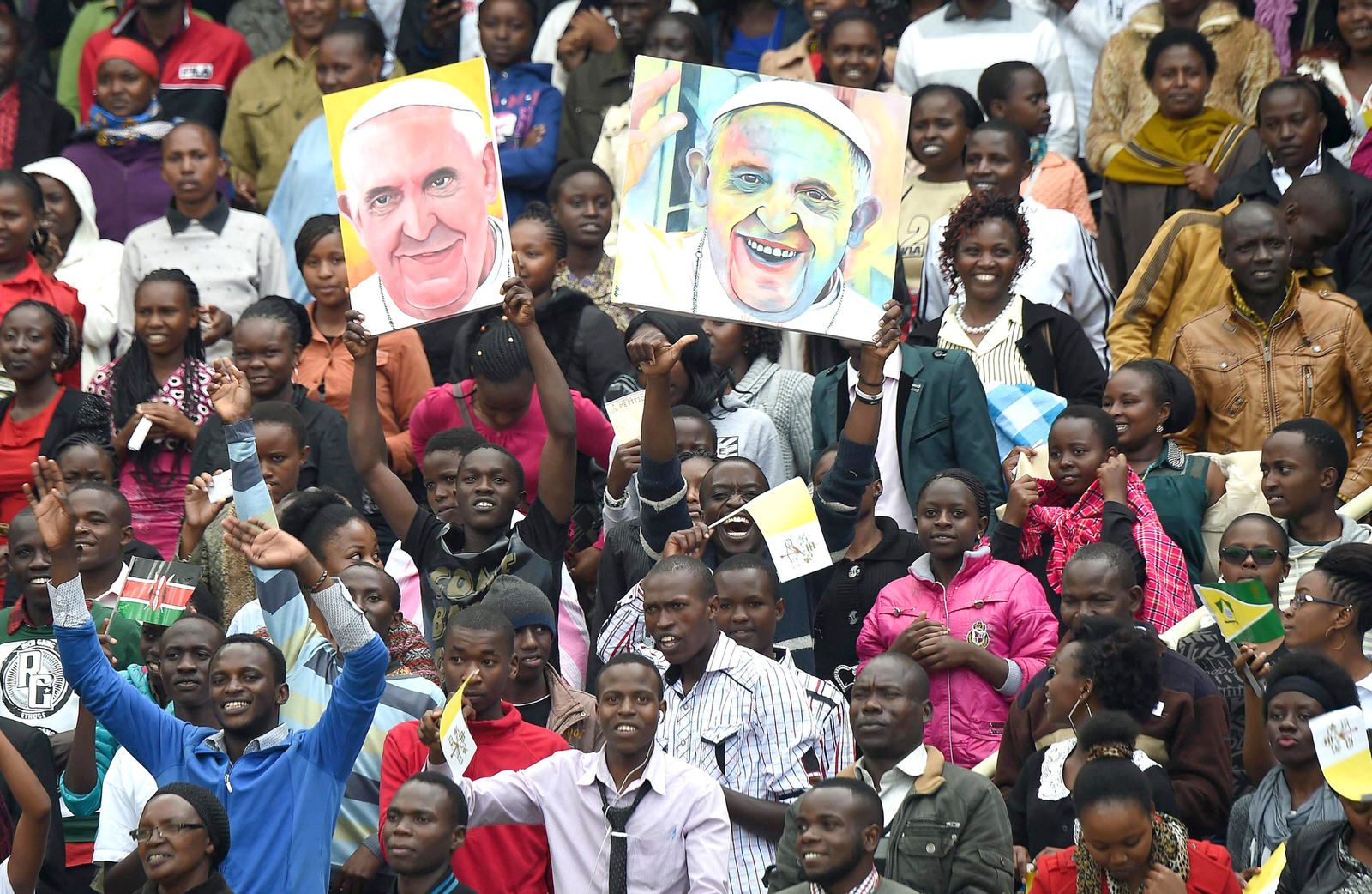

Matutina likened herself and other environmental activists to endangered species: decreasing in number yet hardly multiplying. Yet, despite the challenges, environmental activists now have no less than Pope Francis backing them up.

“Laudato Si naturally boosted our morale and gave us inspiration because before it came out, we were already in the environmental advocacy. With that encyclical, we are so happy because, now, more people will be added to our flock. We used to ask: ‘Where are the other priests, nuns and bishops? This is not only the advocacy of the Benedictines and the Franciscans.’ Now, the Pope is calling on everybody to respond to the environment. He warned us that time is running out and that when the environment takes its toll, it is always the poor who are greatly affected,” he said.

Poverty as motivation

Coming from a poor family herself, Matutina said she felt that her calling was to give hope to the poor. She was the third eldest in a brood of 12. She was born in Bukidnon.

“I came from a very poor family so I know the struggle. I think God wants to use me as His instrument to give hope to the poor,” she said, explaining her motivation for her work with the indigenous people, poor farmers and fisherfolk in Mindanao.

As if it was planned all along, Matutina’s calling led her to join the Benedictine nuns known for their preferential option for the environment and socio-pastoral apostolate targeting the poor.

“We believe that, by protecting the environment and promoting sustainable agriculture, we can help build up a society. It is also part of our apostolate to help empower poor people, like the indigenous people, to protect themselves and their dignity,” she added.

While there are instances when her life was at risk due to mission work, Matutina recalled several triumphs that make the environmental advocacy worth pushing for. The Benedictine nuns helped the indigenous people oppose the mining of Mt. Hamiguitan, a UNESCO Heritage site in Davao Oriental.

“As a community of Sisters, we helped in the negotiations and protected the people who were harassed and even killed for opposing mining. With our help, the people unified their voice before the Barangay Council. Seeing the bulldozers leaving the community gave us joy,” she said.

Matutina and the Benedictine nuns were also instrumental in helping natives of San Isidro town in Mati City. They helped the locals lobby before the Council and eventually urge the governor to cancel a mining permit.

“In truth, we, activists in the environmental protection advocacy, are true nationalist because we do not want other people to exploit us and to deprive our people of their land,” she stressed.

Not anti-mining

Due to their success stories in Mindanao, Matutina has roamed around the country, giving lectures on the threats of large-scale mining to the environment. However, the nun clarified that she is not completely against mining as an industry.

“I am not anti-mining, per se. But when you do mining, you only get what you need. What is happening in Mindanao is that the mining companies get all the land and export it to Japan, China or Australia,” she pointed out.

Given the continual displacement of poor indigenous people due to mining activities, the latest of which is in Surigao del Sur, Matutina said there is still so much to do. But theirs is an advocacy that even some liberal Filipinos are doubting.

“Some critics say that we are technology-averse or anti-development. But, in truth, true development is also about thinking about the common good of all, not only about your profit,” she said.

Germany’s recognition of Matutina’s work in environmental protection has not only affirmed the nun’s intention but also placed the issue to the international media’s attention.

“I am not the one who deserves this award because I am just a representation of the many people who are suffering and are harassed for protecting the environment. There are many IP leaders who deserve it,” she said

“Nonetheless, I am happy to receive it because this award highlights the real situation that we are being harassed. This award is an opportunity for us to educate people about protecting the environment and to let the IP’s voices be heard,” Matutina added.

Matutina received the award from the Weimar City Council on December 10, 2015, coinciding with the International Human Rights Day.

“Our apostolate is grounded on the protection of the environment. With the encyclical of the Holy Father, it is very clear that the protection of the environment is not something new. Pope Francis just reiterated it and said that time is running out, the environment is in pain and we have to do something,” she said.

Matutina is the first Filipino to receive the citation from Germany. But in 2000, the award was conferred to Irish-born Fr. Shay Cullen of the Peoples Recovery Empowerment Development Assistance (PREDA) Foundation for his work in defending the rights of children and women, victims of human trafficking, sexual abuse and exploitation in the Philippines.