In 1997, the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, issued an important document, Towards a Better Distribution of Land – The Challenge of Agrarian Reform. The question of land ownership and distribution had by then become an important issue. Private companies were buying large swath of land from governments, without caring for the rights of indigenous people or of farmers who had traditional access to that land.

The document stated that “the development model of industrialized societies is capable of producing huge quantities of wealth, but also has serious shortcomings when it comes to the equitable redistribution of its fruits and the promotion of growth in less developed areas. While developed economies are not immune to this contradiction, it reaches particularly alarming proportions in developing economies. This can be seen in the persistence of the phenomenon of the misappropriation and concentration of land – that is, that good which, given the predominantly agricultural nature of the economy of developing countries, constitutes the fundamental production factor, together with labor, and the chief source of national wealth. This state of affairs is often one of the main causes of situations of hunger and want, and represents a concrete negation of the principle derived from our common origin and brotherhood in God (cf. Eph. 4:6) that all human beings are born equal in dignity and rights.”

Many agrarian reforms have failed in reducing the concentration of landholdings, and in creating farm units capable of autonomous growth. We have instead witnessed the expulsion of large masses of peasant farmers or indigenous inhabitants from the land and their migration to urban centers, where they enter into a vicious cycle of poverty.

In many countries of the South, governments did not provide the necessary infrastructures and social services in rural areas, nor did they provide technical assistance to small farm owners. In this way, local farmers cannot be competitive with large landholders. Small farmers are often forced into debt. They then have to sell their rights and give up farming.

A new factor is destabilizing the agrarian reform in many countries, especially in Africa. More and more governments are leasing agricultural land in Africa and exporting the produce back to their country, or selling it in international markets. Saudi investors are spending to the tune of £60 million in Ethiopia. In exchange for investments in infrastructure and cash, the investors enjoy tax exemption for the first five years and will be able to export the entire crop. This, in a country routinely hit by famine and where the World Food Program provides food aid to close to 5M Ethiopians threatened by hunger and malnutrition.

Leasing or buying farmland in distant countries is not new. Many international corporations have invested in farmland in the past. New is the size of farmland acquired, and the fact that more and more tracts of land are leased by governments. Leasing such large swath of land is bound to be controversial. Supporters of the deals point out that investors do introduce new technologies and new seeds. Opponents to the projects point out that the land leased to foreign countries is not an empty land. Farmers have used this land for generations. Pastoralist communities use this land to graze their cattle.

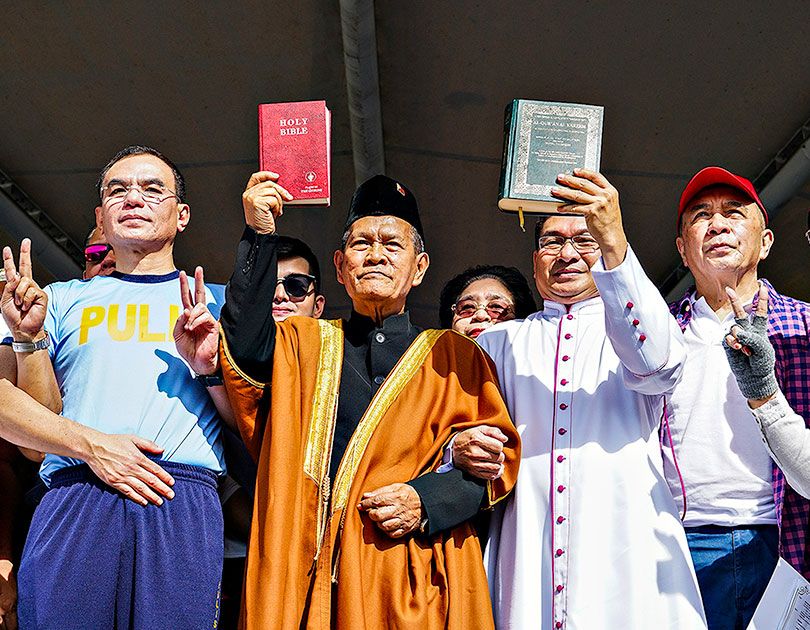

The fight for land ownership then becomes a question of respect to the rights of indigenous people to live in their ancestral land. On the one hand, local people have a right to live in their land according to their cultural ways. On the other hand, the nation has a need to use all available land to produce enough food for all. The insertion of foreign interests only complicates the matter. The social teaching of the Church tells us that land ownership and usage are fundamental issues. They cannot be left in the hands of a few connected people, who may take personal advantage of them. They have to become the focus of public debate, so that all may intervene and a consensus is reached – for the good of all.