The Economist magazine is known for its imaginative and witty obituaries, and for its last issue before the year 2000, it published one on God. The argument seemed to be that the increasing irrelevance of religion in international affairs had effectively rendered God a relic of the past.

Less than a decade later, the same magazine published a special dossier on the rise of the importance of religion, especially in the form of conflict-fuelling fundamentalism, and recognized how wrong it had been to declare God dead. Religion, as the bombing of the Twin Towers and all that followed had proven, was alive and well and continued to play a crucial role on the world stage.

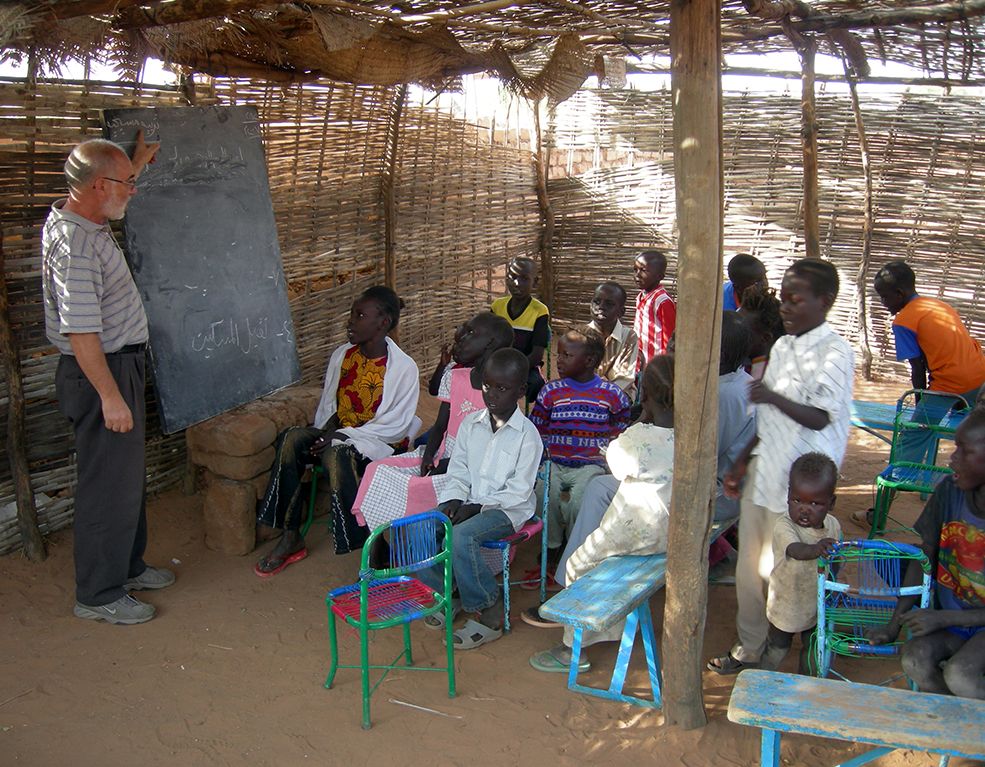

With the rise in religiosity comes the age-long challenge of religious freedom. Hardly a day passes without news of somebody persecuted, tortured, or killed for their faith. From the Christians in Iraq and Syria, to the Muslims in China or in Myanmar, and across a wide spectrum of other faiths and latitudes, religious people continue to pay the ultimate price.

The scope of the problem of life-threatening religious intolerance can, however, blind us to another aspect of the religious freedom problem which has increasingly been making itself felt in the West, where persecution also exists, but more than threatening the body, it threatens conscience.

Can these two realities be compared? Can one seriously equate somebody losing their job for refusing to cooperate in abortion with being killed because they refuse to recant their religion? A simple exercise provides the answer. What do we call somebody who sacrifices their values and their conscience to save their life? A coward at worst, weak at best. And what do we call somebody who sacrifices their life to preserve their conscience? A hero in the secular world, for Christians a saint.

We see that threats to conscience are in fact no less serious to somebody who takes their religion seriously, than are threats to physical safety, even though the latter may seem more shocking to the general public.

New Rights Against Old Beliefs

Threats to conscience come in many forms in the current world, and affect believers of many types. One relatively new phenomenon, however, is the clash between conscience and so-called “new rights,” which include the alleged right to abortion, or homosexual marriage, for example.

An already famous example is that of Jack Phillips, a Christian who owns a cake shop in Colorado, USA. In 2013 he was asked to make a cake for a same-sex wedding but he respectfully declined, saying that he is personally opposed to the idea that people of the same sex can be married, and therefore would not cater to the request. Mr. Phillips has always made it clear that he has no problem serving homosexuals, it is the nature of the institution this one cake aimed to celebrate, that he opposes. The result was six years of legal wrangling, with the baker losing appeal after appeal until the United States Supreme Court finally came out in his favor. The court found that in its case against him, the State of Colorado had shown “clear and impermissible hostility” to his religious beliefs.

Unfortunately, this is not a unique case as there are dozens if not hundreds in the USA alone, and many others in Canada and in Europe. And these are only the ones we know of. How many people would have had Mr. Phillips’ energy and will to endure all these difficulties? How many don’t just back down the minute legal action is threatened? A recent survey in the United Kingdom showed that among university students, self-censorship is now common, as young men and women have learned that they can get into trouble for saying what they truly think when it comes to contentious matters.

One interesting case of somebody getting into trouble for voicing an opinion involves a Member of Parliament in Finland. In 2019 Mrs. Päivi Räsänen published a tweet in which she criticized the national Lutheran Church–to which she belongs–for coming out in support of a Gay Pride march. She illustrated her post with an image of a Bible verse condemning homosexuality, and as a result, she was called in by the police for interrogation and has been accused of “inciting ethnic unrest,” which, if convicted in court, could lead to a six-year prison sentence.

Of course, one is free to agree or disagree with Mr. Phillips or with Mrs. Räsänen. But the real question is: do we agree that their opinions constitute a crime. And if so, then what opinions are safe?

Indiscriminate Discrimination

As the European Parliament approves reports that would have abortion classed as a universal right, and the President of the French Republic calls on the EU institutions to make abortion a human right, it can be easy to think that this is all a manifestation of what has been termed Christianophobia. But the truth is that all religions have cause for concern, and Muslims and Jews continue to be the victims of intolerance and discrimination in Europe as well.

Over the past years, for example, many countries have moved to ban the slaughter of animals according to the ancient “halal” and “kosher” methodologies. Jews and Muslims continue to adhere to strict dietary rules, and one of the basic tenets is that animals must be healthy and conscious at the time they are killed. However, this clashes with modern ideas of animal rights.

The European Union has declared that all animals must be unconscious when killed in a slaughterhouse, but it allows for exceptions in the cases of religious freedom. Nonetheless, country after country has been doing away with those exception clauses in national legislation meaning that these religious communities are left with no option but to eat only imported meat and, of course, a feeling of not being welcome in the societies in which they live.

How much of this is the direct result of discrimination is up for debate. In some cases, the laws are presented by animal rights parties, which consider that animal welfare trumps religious freedom, but in others they are presented by far-right populist parties and seem motivated more out of hostility for minorities.

Other cases involving Muslims and Jews are more insidious. A local German court at one point banned circumcision for religious purposes, a crucial practice for Jews, and to some extent for Muslims also, and it had to be the Federal Government which put the issue to rest, making it legal again. The issue has come up in other countries, such as Iceland and Finland, though not passed into law.

A handful of countries in Europe, and some provinces in Canada, also ban the wearing of religious garb, such as veils and headscarves in some spaces. France has been particularly zealous in this regard, culminating in the absurd scene of police fining a woman in a “burqini” for “not wearing an outfit that respects good morals and secularism”, in Nice, in 2016.

Discrimination Or Illiteracy?

Many believers do not hesitate to put all these cases down to outright hatred of religion and of people with faith. But the reality may not be so simple.

When the circumcision debate was raging in Norway, Anne Lindboe, the ombudswoman for children, suggested Jews and Muslims abandon circumcision and replace it with something symbolic. The fact that an educated person would say such a thing shows that they have no clue at all about the importance of religion and its role in people’s lives. But there is not necessarily any malice, nor was there any in the face of Helén Bjornsdotter, mayor of Södertälje, Sweden, who matter-of-factly stated in 2018 that of course there was no place in society for religious schools. To both these women, and legions of other people, the idea that religion and belief could be central to somebody’s life seemed completely inconceivable.

This, unfortunately, is becoming increasingly common. God may not be dead, as even The Economist was forced to recognize, but that doesn’t mean that people know Him, or understand how important He is in the lives of those who do. In the Western world, where the number of people with any knowledge of religious issues continues to drop, cases like these are bound to become more frequent.

Which, of course, begs the question: Where assaults on religious belief and conscience become commonplace, can attacks on health and life really be that far behind?