Somewhere in the Western Visayas region in the Philippines lies Boracay, an island famous for its powdery white sand, crystal cool waters, magical sunset, and endless partying at night.

Several international magazines dubbed Boracay as one of the world’s best island getaways. Travel + Leisure magazine named it as 2012 No.1 World’s Best Island, beating out Bali which ranked number two. It also bested other Philippine Islands in Condé Nast Traveler’s 2016 Readers’ Choice Awards as the Best Island for 2016.

Year after year, the number of tourists visiting the island also increases. For 2017, a total of 2,001,974 tourists visited the place. Both local and international visitors have greatly contributed to the island’s revenue.

According to government data, the island generated a total of P56,147,744, 220.60 in tourism receipts last year, with a significant 14.83 percent increase from 2016’s P48,895,469,783.40. Top 10 foreign tourists visiting the island are as follows: Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese, Americans, Malaysians, British, Saudi Arabians, Australians, Russians, and Singaporeans.

Despite its growing popularity globally, only a few people know that the whole island used to be home to the Ati people, one of the country’s indigenous peoples. They had been in Boracay long before the earliest Visayan migrants came into the Island.

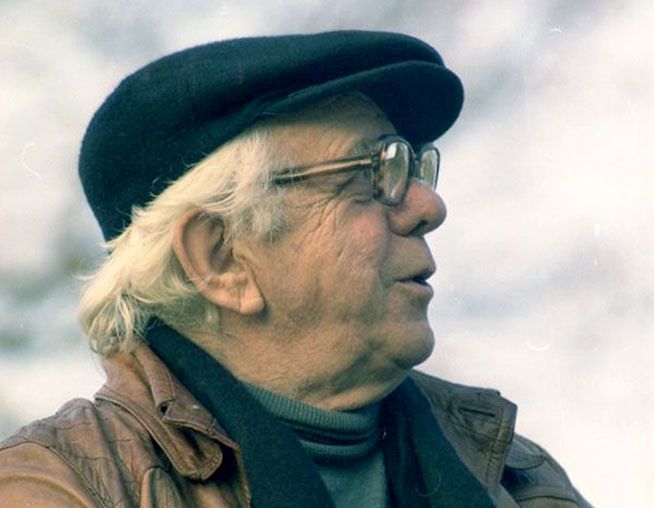

Dr. Alicia Magos, a Filipino anthropologist proved the Ati’s indigeneity in the island. In spite of Boracay Island’s large scale commercial tourism and massive influx of migrants, traditional Ati life remained in the form of Pangranso, a non-sedentary way of life where they moved from one place to another.

Issues Confronting The Atis

By the 1970s, the Atis’ life had changed dramatically when more settlers got the opportunity to establish beach resorts and other businesses on the island.

Commercialization and tourism gradually displaced the Atis to a small property located at the island’s back beach which was owned by a rich family. From a tribe who used to freely roam the island, they were forced to live as informal settlers in what used to be their home.

With the help of nuns from the Daughters of Charity, the Roman Catholic Church, and various support groups, they called for the recognition of their right to land and ancestral domain.

After almost a decade of relentless lobbying for the recognition of their rights, the Atis finally received their Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title for the 2.1 hectare-portion of the 1,032-hectare island on January 21, 2011. This is by far the smallest ancestral domain in the Philippines with other domains covering thousands of hectares of land.

Despite the legal recognition, the Atis were not able to possess the ancestral land right away and experienced different forms of harassments. Cases have been filed to deny members of the Ati community on their land rights claim including the cancellation of CADT filed at the Regional Trial Court (RTC).

Property claimants from rich and influential families have also erected houses and fences around the disputed land and even posted a billboard prohibiting entry to the area. On November 19, 2009, some residents of Boracay filed a protest on the proposed establishment of an Ati Community in Boracay Island. They considered the presence of the Ati ‘damaging’ to the tourism industry of the island.

Community Initiatives

Racing against time, these issues have prompted the Ati to take the risk of installing themselves at their new home. On 17 April 2012, some 200 members of Boracay Ati Tribal Organization (BATO) took the risk of installing themselves inside the vacant portion of the 2.1 hectare ancestral domain awarded to them.

In 2013, a five-year Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development and Protection Plan (ADSDPP) was drafted and published by the community in partnership with the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples and Assisi Development Foundation.

It detailed the Ati’s struggle to self-determination, the condition of the ancestral domain, their sustainable development plans and programs, implementing mechanisms and policies, and pledges/commitments from various organizations and agencies to help protect and promote the rights of the Ati.

Five years later, the community has implemented most of the plans indicated in their ADSDPP. Both tangible and intangible projects and programs were realized in collaboration with various support groups and individuals within and outside the ancestral domain.They built houses, a chapel, a livelihood center, a school, the Ati living heritage center, and recreation areas in their new community.

Continuing Struggles

As soon as the members of the tribe were able to occupy a portion of what has been awarded to them, cases were filed before the court by claimants, Banico & Sanson to cancel the title issued to the community.

On February 22, 2013, on his way home from a meeting in their old settlement, Ati leader and spokesperson, Dexter Condez was shot dead. The main suspect was a security guard of one of the claimants. His death was a major loss for his people, yet, it also strengthened the community’s resolve to fight for what was originally theirs from the beginning.

Workers of one of the claimants destroyed part of the perimeter fence of the community on December 6, 2017. The destroyers presented a ruling from the Court of Appeals citing that NCIP has no jurisdiction over cases involving indigenous peoples and non-indigenous peoples

What’s Next?

The Ati people’s struggle is just one of the many struggles that indigenous peoples face across the globe. It speaks a clear message – social justice remains elusive for most indigenous communities. The 2.1 hectare property is so small compared to lands sold or used for purposes of making the rich richer and the poor poorer.

The current six-month closure of the island is also another source of uncertainty and insecurity for the community. On one hand, they are hopeful that the closure would return Boracay to the pristine island it used to be. On the other hand, they are worried because there is no concrete assurance yet that the court will honor and uphold the CADT awarded to them in 2011.

And if the court does not uphold the tribe’s rightful ownership of the land, where would the Ati people go?