In the morning of February 12, 2005, at the countryside of an isolated town called Anapu, in the immense Amazon area, Sr. Dorothy Stang, an American religious woman living and working in Brazil for almost forty years, woke up early to walk to a community meeting to speak about the rights of the Amazon. Ciero, a farmer she had invited to the meeting, was a couple of minutes behind the Sister so he could see her and was able to hide from the two armed men who followed her.

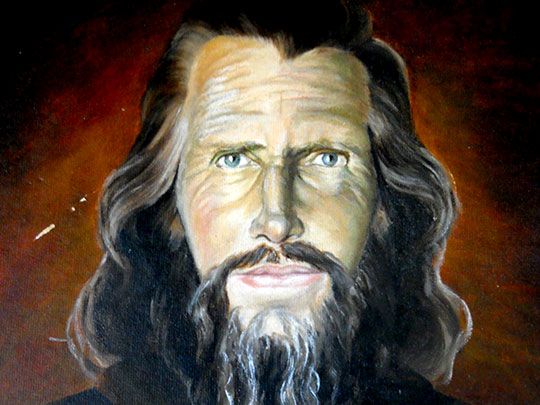

As she progressed on, she was blocked by two men, Clodoaldo and Raifran, who worked in a livestock company. They asked her if she had any weapons, and she claimed that her only weapon was her Bible. She then read a passage from the Beatitudes: “Blessed are the poor in spirit…”

She continued a couple of steps but was suddenly stopped when Ciero called her, “Sister,” as she was held at gunpoint by Raifran. Then Clodoaldo nodded and Raifran fired a round at Sr. Dorothy’s abdomen. She fell face down on the ground. Raifran fired another round into her back, then fired all four remaining rounds into her head.

Her body lay on the dirt road all day, nearby witnesses later said, because they were afraid they would be shot if they moved it. As it rained, her blood mixed with the soil, an extreme symbol of her love for that land which had become hers. She fell as a martyr: the conclusion of a heroic commitment.

Thousands of people, from peasants to politicians, converged on the remote Amazon town to bury the bullet-ridden body of the elderly American nun. After an all-night vigil, mourners filed slowly past the flag-draped coffin of Sr. Dorothy, in the small, single-roofed church of Anapu, the jungle town of seven thousand residents that Sr. Dorothy had adopted as her own. Some held up a handkerchief stained with her blood, her cloth shoulder bag or saplings to symbolize the jungle she had died defending.

A crowd followed her coffin down a dirt road to the graveyard, singing: “They killed one more Sister but she will rise again. The people will not forget.” “I feel like a river without water, a forest without trees. It is like losing a mother,” one of those present exclaimed.

Nearly one thousand five hundred kilometers in the southeast, in the capital Brasilia, cabinet ministers compared Sr. Dorothy Stang to Chico Mendez, the celebrated defender of the rain forest who was gunned down in 1988.

A dream come true

Sr. Dorothy Stang was born on July 7, 1931, one of nine children, to a devout Roman Catholic family in Dayton, Ohio, USA. As a young girl, Dorothy had always had her heart set on becoming a missionary. It was a dream of hers to educate poor children and spread the message of Christ to those who have not heard of Him.

Driven by this passion, the young Dorothy joined the Sisters of Notre Dame of Namur in Cincinnati, shortly after completing high school, in 1948. In 1956, she took her religious vows. From 1951 to 1966, she taught elementary classes.

It was the time when the progressive practices of liberation theology were sweeping through the Catholic Church in Latin America. Priests and nuns exchanged their habits for jeans and T-shirts, left the cloisters to work in shantytowns and poor rural communities, alongside the poor, and dispossessed. Sr. Dorothy was one of them.

Her missionary dream finally came true in 1966 when she was assigned to a post in Coroatá, Brazil. There, she immersed herself among the poor peasants and farmers who dwelled in the Amazon Basin. It soon came to her attention that many of the villagers were not aware of their land rights and the wealthy landowners and ranchers were taking advantage of them. Sr. Dorothy began to study the laws of Brazil and campaigned to prevent the villagers from being further exploited.

Insertion

Sr. Dorothy made frequent visits to the villages scattered throughout the Amazon Basin. She taught the women to sew and sell clothing to finance the building of a dam that provided electricity to the community. She was responsible to teach the men of the villages to be faith leaders. She set up dozens of Basic Christian Communities and taught them the Gospel. She launched 23 schools and created a structure for the poor to claim their land.

Feisty and energetic and loving, she remained faithful to the poor, to the ruined Amazon, and so, to the Gospel and the God of justice and compassion. Beautiful stories are told of her dedication: how she fed the hungry, built community, lived in destitution. How she confronted illegal loggers and corrupt ranchers, the class who stole land from the poor, kept them in misery, and bought off the police, the military and the government.

The CPT (Land Commission) had been created by the Brazilian bishops in 1975 in response to the mounting violence in the Amazon region, as landowners used gunmen to clear peasant farmers from disputed land and Sr. Dorothy became an active member of it. Like all CPT workers in the Amazon, she knew that her life was threatened, although she believed that being a nun would protect her.

Actually, death threats rained down on Dorothy for years, along with insults and hate mail. Ranchers took aim at the community center for women that she had founded and riddled it with bullets. On one occasion, the police arrested her for passing out a “subversive” material. It was the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

A dangerous fight

Over the years, the work became progressively more dangerous for the Sisters in Brazil and for the farmers and their families. As the world discovered the vast possibilities offered by the rich natural resources of the Amazon rain forest, people with more limited and self-centered goals began to plan ways to capitalize upon them. Gradually, loggers, ranchers, land speculators, and agribusiness became the dominant forces in the region, victimizing the poorer farmers and destroying the rain forest.

The Amazon rain forest is one of the largest remaining virgin forests on earth. Its original trees and vegetation comprise 40% of all the tropical rain forests in the world. The forest hosts 50% of the world’s plant species and is home to 20 million people. In addition, 20% of the earth’s fresh water reserve runs through the Amazon River Basin.

Sr. Dorothy understood that the rain forest, also called the earth’s lungs, plays a critical role in the exchange of gases between the biosphere and the atmosphere. Her frustration grew as she witnessed the destruction of this natural resource so vital to her people’s and the planet’s future. She saw the forest and the people plundered for financial gain by illegal logging operations, land speculators, and cattle ranchers. She witnessed political leaders allowing the destruction to continue.

Hired killings of human rights advocates, environmentalists, and farmers account for one-third of the violent deaths in the region each year. The goal of these calculated murders is to eliminate opposition to the clear-cutting and burning of the forest so that fields of soybeans can be planted, trees can be logged, and cattle can graze. Another goal of the killings is to eliminate those who empower and educate the peasants; and finally the killings are meant to intimidate the farmers and keep them ensnared in an endless cycle of debts, akin to slavery. Sr. Dorothy became a prime target.

She was undeterred

In 2002, the death threats intensified. The mayor of the nearby town said: “We have to get rid of that woman if we are going to have peace.” A list of people with “bounties” on their heads circulated. Atop the list was her name: Stang ($20,000). But she was undeterred.

In 2004, although she knew she was putting her life even more at risk, she went to Brasilia to give evidence before a congressional committee of inquiry into deforestation. She named logging companies that were invading state areas. Environmental organizations reckon that 90% of the timber from Para state is being illegally logged. Loggers reacted by calling her a terrorist and accused her of supplying peasant farmers with guns. She and other local leaders began to suffer direct death threats but she refused to be intimidated and continued her work with the farmers.

Visiting her family and community in Ohio a few months before she was killed, she told one sister: “I just want to sink myself into God.” “I look at Jesus carrying the cross,” she said a few days before her death, when asked by a novice about her prayer, “and I ask for the strength to carry the suffering of the people.” A day before she died, she said: “If something is going to happen, I hope it happens to me because the others have families to care for.” Then, in that fatal morning, the gunmen came.

Recognitions

Before her murder, Sr. Dorothy was named “Woman of the Year” by the state of Para for her work in the Amazon region. She also received the Humanitarian of the Year Award from the Brazilian Bar Association for her work of helping the local rural workers. Since her death, Sr. Dorothy has been widely honored for her life and work by the United States Congress and by a number of colleges and universities across the Unites States. She was posthumously awarded the 2008 United Nations Prize in the field of Human Rights.

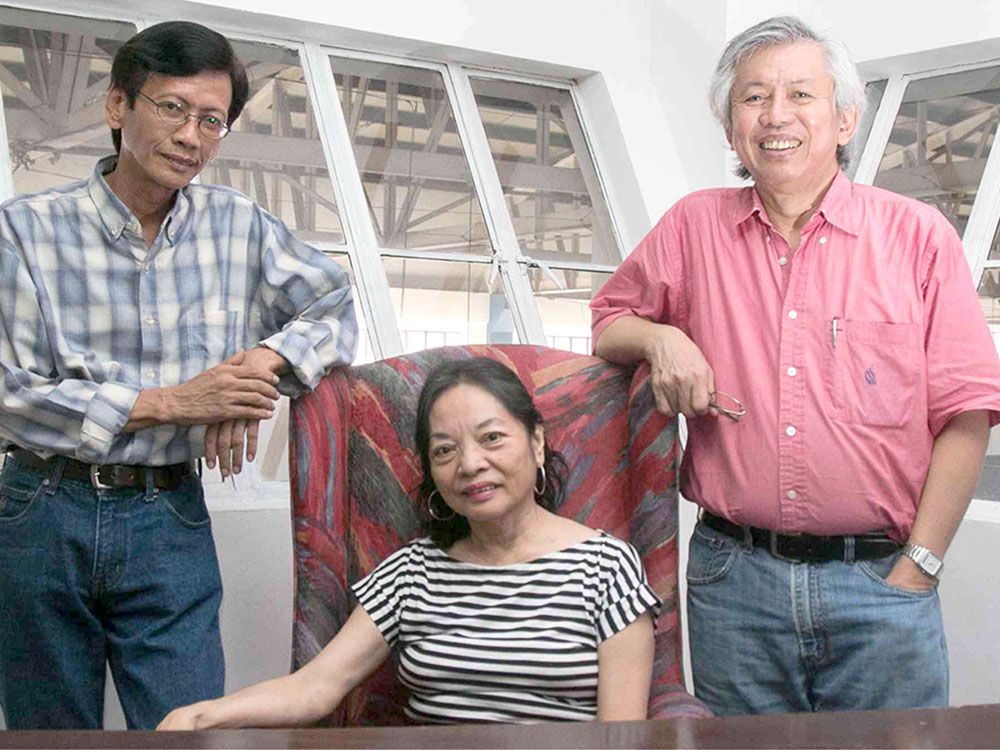

Her story is narrated in countless articles in newspapers and magazines and described in books. The most remarkable is the powerful biography, Martyr of the Amazon: The Life of Sister Dorothy Stang by Roseanne Murphy. In 2008, the American filmmaker, Daniel Junge, released a documentary titled They Killed Sister Dorothy, narrated by Martin Sheen in the English version. In 2009, Evan Mack composed an opera based on the life of Sr. Dorothy Stang. Angel of the Amazon depicts her life’s work, her devotion to her mission with Brazilian peasant farmers, and the events that sent her on the path of martyrdom.

This is what Fr. John Dear, SJ, champion of pacifism, wrote: “I suspected early on that Sr. Dorothy had attained great moral heights. Anyone who leaves their homeland, spends four decades serving the poorest of the poor in Amazon, and defends the forest – long before anyone ever thought of an environmental movement – must possess enormous commitment, faith and vision.”

Her cause for canonization as a martyr and model of sanctity is underway in Rome, within the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.