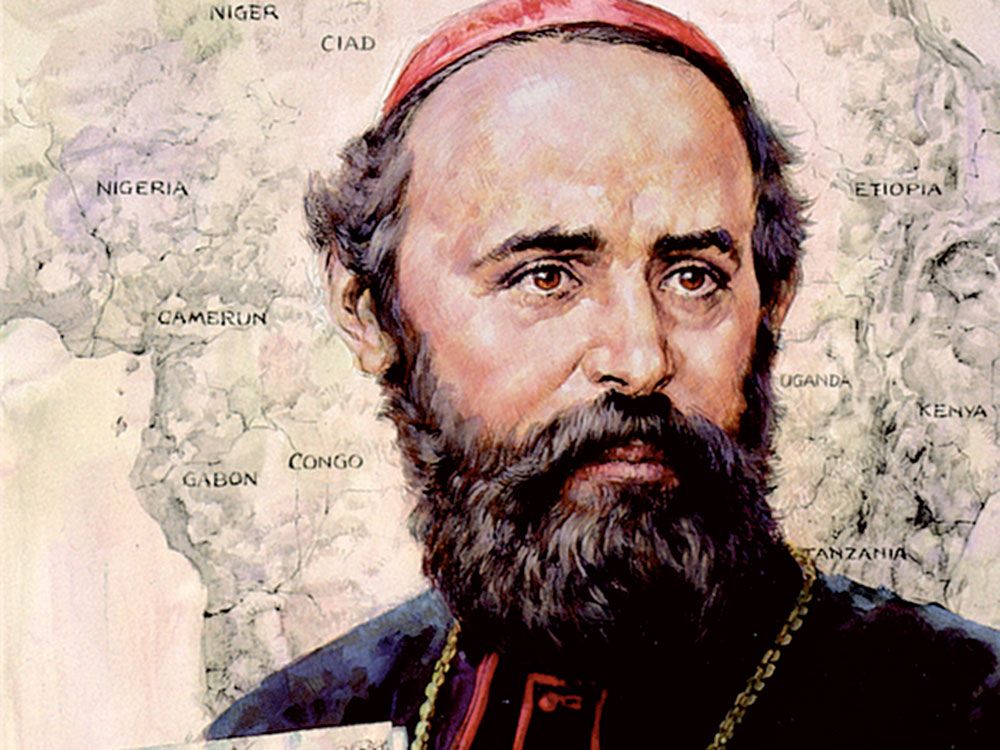

Argentina is the eighth largest country in the world and the largest Spanish-speaking one. The country has its roots in the Spanish colonization. The beginning of the 19th century saw the declaration of its independence. The country, thereafter, enjoyed relative peace and stability, with massive waves of European immigration aiming at occupying its immense pampas (prairies). This is the theatre of the adventures of Fr. José Gabriel del Rosario Brochero and his rough pastoral life.

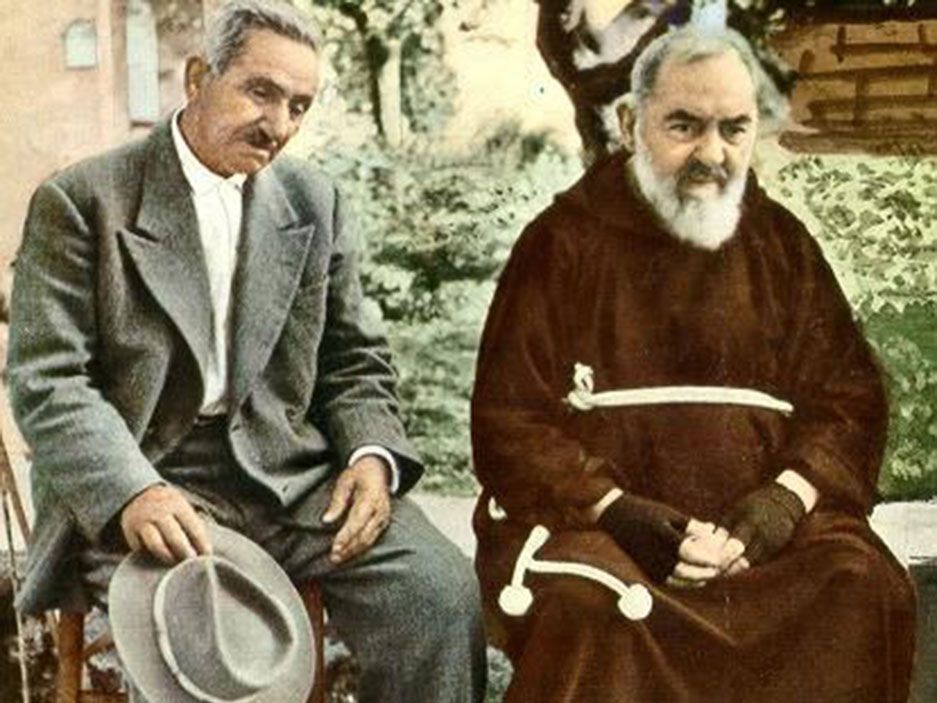

The consequent edginess of Fr. José Gabriel’s character became an obstacle during the process of beatification and slowed down the same process, but did not alienate the people’s love and empathy for him or make him less simpatico to his people. It is certain that Pope Francis had a great estimation for Fr. Josè Gabriel Brochero, El Cura (the priest) Brochero.

We can bet on it since at the 2013 Chrism Mass, the first in his new capacity as Bishop of Rome, Pope Francis asked priests to be pastors who have “the smell of the sheep about them.” He was certainly thinking of him as it became clear in the Beatification Mass, when he defined Fr. José Gabriel as a pastor who had about him the smell of the sheep, who made himself poor with the poor, who always fought to stay close to God and people, who did much good and kept doing much good as “God’s caress to our suffering people.”

An original pastoral approach

Jose Gabriel del Rosario Brochero was born on March 16, 1840 in Argentina as the fourth of ten children to Ignacio Brochero and Petrona Davila; he had two sisters and the others were brothers. The two sisters became nuns. He was baptized the following day along with the registration of his birth.

He commenced his studies to become a priest at the College Seminary of Our Lady of Loreto when he was sixteen. As a young man he had joined the Dominican Third Order. He was ordained to the priesthood in the Diocese of Córdoba on November 4, 1866 at the age of 26 and celebrated his first Mass the following December 10.

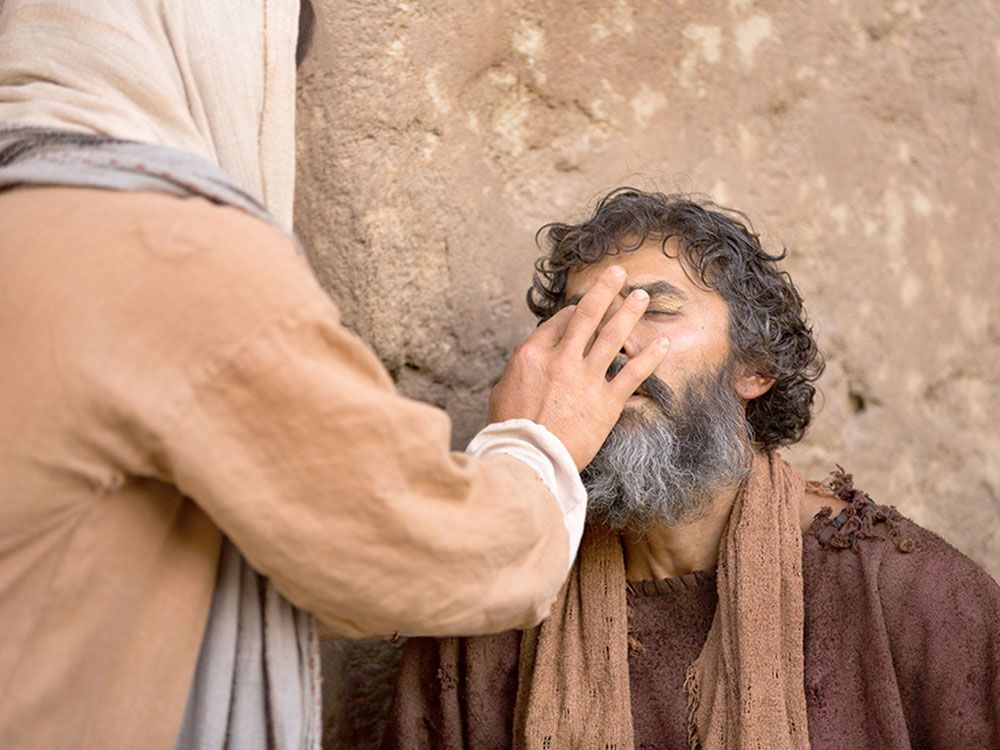

Just ordained as a priest, Fr. José Gabriel started his frontline ministry in the city of Cordoba which was infested by a cholera epidemic that claimed more than four thousand victims, the majority of whom saw our young priest defy the danger and kneel beside the sick people in order to administer the last sacraments to them.

Soon the emergency was over and the ordinariness of ministry came with his appointment to the parish of Saint Albert, a community of ten thousand people scattered in more than four thousand square kilometers, a parish that required three days journey from Cordoba on the back of a mule.

It is the same distance to and fro that he soon requested his parishioners to cover when, in groups of 50/70 every time, he accompanied them to the city to do the Spiritual Exercises according to the style of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, often under the threat of snowstorms.

It was an unusual and challenging pastoral proposal directed to people who were farmers, animal keepers, almost illiterate and yet they came back from it wholly renewed and with the resolution of changing their lives.

Fr. José Gabriel believed so much in this pastoral choice that, eventually, he decided to build a retreat house at Villa del Transito in order to eliminate the time required for the journey: a building which now bears his name and through which some forty thousand people may have passed during Fr. Brochero’s forty years of ministry in the area.

El Cura Gaucho (the “cowboy” priest)

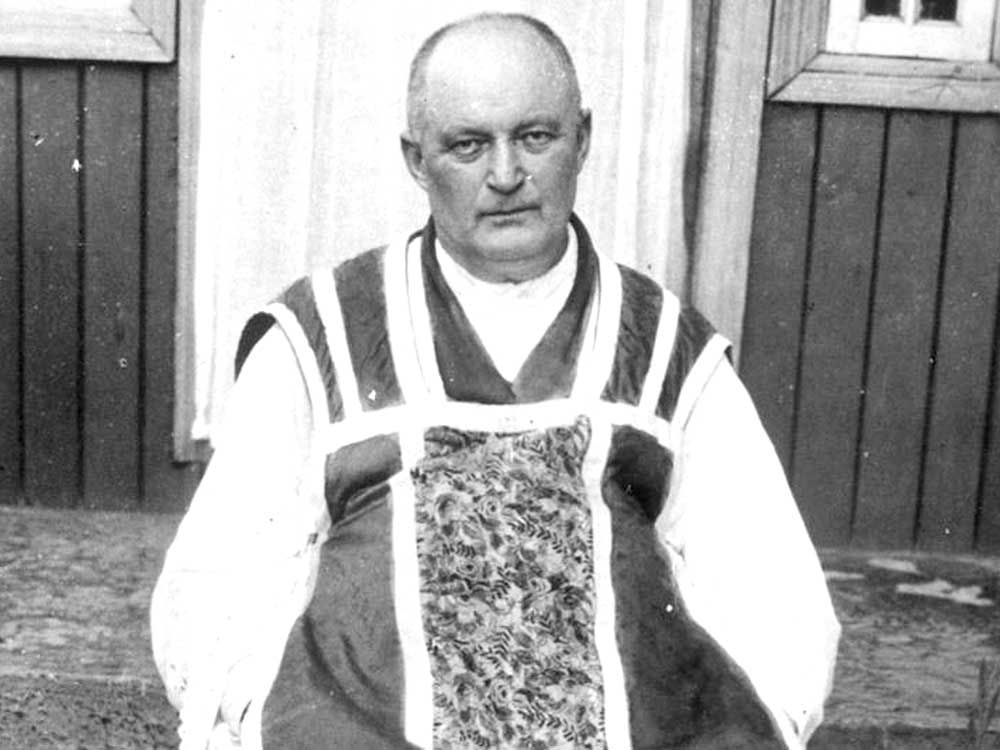

He was certainly not a parish priest likely to spend his life in the sacristy. Fr. José Gabriel chose to make his own the life of those to whom he was assigned to preach the Gospel, knowing that only in that way he could reach straight to the heart of those simple people.

Starting from his mount, a female mule (called Malacara, Sad Face) which in itself was not very remarkable, up to his attire which was very similar to that of the common people, the classic poncho (cloak) over his black sotana (robe) and a large sombrero, everything was commonly shared with his people. Add to that his prayer book and the missal, kept together by a red ribbon so that they may not come apart during the long journeys, and without forgetting the necessary Mass kit and a small statue of Our Lady.

Precursor of all the street priests, in perennial movement in order to visit all the “peripheries,” he used to reach the most hidden corners of his parish under sun or rain, especially when it was the case of a dying person because the “cowboy” priest used to say: “Otherwise, the devil will steal a soul from me.”

Without losing sight of the supernatural purpose for which he is working, Fr. Brochero yet came to the help of the needs of his parishioners who were “abandoned by everybody, but not by God” as he used to say. To this aim he built roads, where there weren’t any, he opened schools where the government didn’t reach, health centers where doctors never treaded, homes for abandoned girls, nurseries, chapels, shelters, irrigation canals, a cemetery, an aqueduct, a post office and even the extension of a railway.

His way of speaking was simple and straightforward, a pastoral conversation, in order to be understood by people with almost no education who did not know any other language but their dialect. In his sermons, he used examples from everyday life, episodes and anecdotes easy to understand, employing terms familiar to farmers and shepherds, like when he explained to them that God is like the lice because He clings to poor people not to the rich.

The strategy of “incarnation”

We could hardly imagine how many and what kind of doubts a talking and writing style of this kind may have provoked in censors and theologians during the process of canonization, to the point of considering it too low and even vulgar, forgetting that the holy priest in question had obtained the title of Master of Philosophy with flying colors, in Cordoba University. Actually, his modest ways were a strategy of “incarnation.”

At any rate, his humble style of relating to people was successful if we consider only the fame which surrounded the “cowboy” priest during his lifetime so much that in 1883, at Cordoba, they distributed his biography and, in 1906, his name found its way in school textbooks.

In 1898, he was forced to retire because of poor health since he could no longer bear the killing rhythm expected from being a parish priest. He was, therefore, named Canon at Cordoba Cathedral but he could not resign himself to that type of sedentary life. Four years later, in 1902, he was once more given parish responsibility at Villa del Transito. He started again with the same rhythm and style without caring for the caution his poor health required.

It looks as if he neglected even the most elementary precautions when he used to deal with caring for the sick to whom he had always showered his preference and attention. And thus, one fatidic day, he was affected by a contagious infection because he did not refuse to share the famous Argentine beverage, mate, with some lepers he was assisting.

Affected by leprosy

Suffering the devastating effects of leprosy, Fr. José Gabriel was forced to leave the parish for good in 1908 and retreat to his home place where his sister took care of him. Practically blind and deaf because of leprosy, he started his calvary with the disposition from God of, as he said, “preparing my end and praying for people of the past, present and future until the end of time.”

Even in this diminishing condition, the parishioners of Villa del Transito came to fetch him and take him to their place in 1912 and there he contributed to the completion of the only initiative he had left unfinished: the railway terminal.

He was now completely blind and still he celebrated Mass using the text he knew by heart, the Mass of Our Lady. On January 26, 1914, he was heard whispering: “Now I have all the tools that I need for the journey.” His heart then ceased beating and he peacefully fell asleep for the eternal rest.

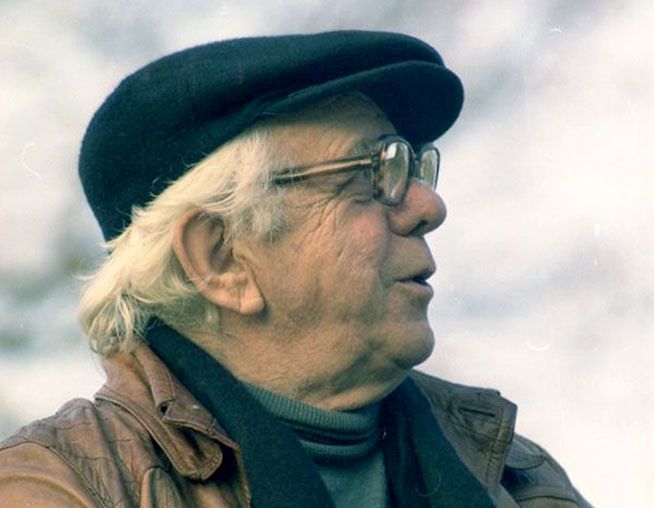

Immediately, his parishioners of the Argentine pampas and, with them, the whole country, paid him the highest honors and passed on his memory: his holiness was plain to them and didn’t need a process. The process of beatification, on the contrary, took more them fifty years because of the hesitations of the experts: the rough personality of the “cowboy” priest didn’t easily fit into the usual patterns of holiness.

But, eventually, the truth prevailed because of the convincing strength of the miracles that happened through Fr. José Gabriel’s intercession. On October 16, 2016, an Argentine pope, Francis, concluded the long but successful process with the solemn canonization: the “cowboy” priest is now a saint!