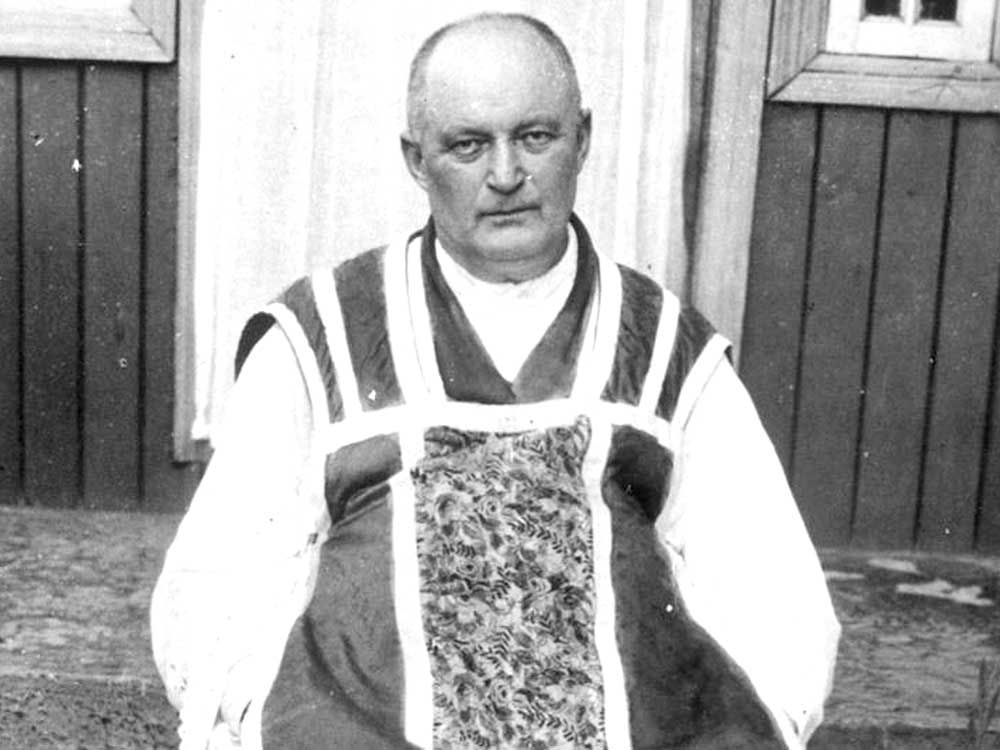

The servant of God was born on December 22, 1904 in Berdyczów, then in Polish territory, these days part of Ukraine. He received baptism, a few days later, on December 26. Two years after his mother’s death, his family fled from the Bolshevik invasion and settled in Western Poland, in the small village of Swiecica, between Lublin and Krakow.

In 1921, Wladyslaw attained his diploma of matriculation in Krakow and began studies at the Faculty of Law at the Jagellonian University, where he then graduated in jurisprudence. During these years of study, he took active part in the Neighbors Academic Circle founded to help poor students coming from the eastern parts of Poland.

It was during this time that the young Wladyslaw began to feel a call to the priesthood and, in 1926, he joined Krakow’s Major Seminary, studying theology at the Jagellonian University while, at the same time, undergoing solid spiritual formation. He was ordained priest in Krakow Cathedral in 1931 by the future Cardinal Adam Sapeiha who, in 1946, would also ordain Karol Woytyla.

He worked for five years as Parochial Vicar, first in Rabka, then in Sucha Beskidzka, devoting himself to intense works of charity, and to catechesis in the schools. In 1936, he volunteered to go to the eastern region of Poland, from where his family hailed. He taught catechism in several high schools, devoted himself to the Christian education of young people and taught sociology in the seminary in Luck. He worked for the Diocesan Catholic Action, and was appointed director of the Higher Institute for Religious Studies, working also for the magazine Catholic Life. In 1939, after incardination in the diocese of Luck, on the outbreak of World War II which followed the Soviet occupation of Poland, the Bishop appointed him parish priest of the cathedral in the city.

Thanks to his deep spirituality, his intelligence, his gifts of prudence and balance, and a good command of the Russian language, he worked hard to defend religious freedom and the Church’s right to continue its pastoral and charity work. In that terrible period, Fr. Bukowinski gave himself untiringly to visiting and giving material help to the sick and old, and bringing to them the sacraments. He secretly met and consoled the Polish people sentenced by the Soviets to deportation to Siberia and to Kazakhstan.

13 years of hard labor

In 1940, the servant of God was arrested by the Soviets and sentenced to eight years of hard labor. With the rapid advance of the Nazi Army, the fleeing Soviets began to execute their prisoners. Fr. Bukowinski is certain that, on June 23, 1941, he was the object of a miracle; he survived a mass killing by firing squad. The bullets failed to hit him and, lying amongst his dying companions, he managed to give them absolution.

After the return of the Red Army, at the beginning of 1945, he was arrested a second time and put in gaol in Kiev, along with the Bishop of Luck and some other priests. Accused of being a spy for the Vatican and of illegal religious activities, he was condemned without trial to 10 years of hard labor. In 1950, he was sent to work in the copper mines in the labor camp of Zezkazgan in Kazakhstan.

Even in these excruciating circumstances, Bukowinski lived his daily Eucharist in a special way, celebrating Mass before dawn, when everyone was asleep, kneeling before a camp-bed that served for an altar. He made use of every occasion for apostolate: visiting the sick in the camp’s infirmary, he brought them the sacraments and preached to them in several different languages.

“At times, Divine Providence works through atheists, who sent me there, where a priest was needed” (from his Memoirs). This servant of God witnesses to us that you can become a saint, that is to say, realize fully your own humanity, in any situation at all, even the hardest and most painful.

He never complained, not of those who had condemned him, nor of those who mistreated him. Only once, in his Memoirs, does he mention a brutal slap he was given on the face, as punishment for having gone to another hut to hear confession of a young prisoner; later he was to see this slap as an act of mercy on the part of the guards, who could even have put him in solitary confinement. Altogether, Fr. Bukowinski served 13 years, 5 months and 10 days of hard labor.

In August 1954, he was freed from the camp and deported to Karaganda, where he worked as a janitor on a building site, while secretly devoting himself to the apostolate. He was the first Catholic priest to reach there after World War II. He set himself to serve the Catholics of both Polish and German nationalities, as well as Eastern rite Catholics. When invited, he would give baptisms, prepare people for confession and first communion, and celebrate marriages.

Some people would travel 200 miles to confess to him and to attend Mass, which he celebrated in secret in private homes, with the curtains drawn. As a deportee, he was obliged to present himself every month at the Commissariat to give precise details about where he had been and what he had done. He always said he was a priest and as such had the duty to offer priestly service.

Crucial decision

A decisive moment for his vocation was in 1955; he refused the chance to return to Poland and decided to opt for Soviet citizenship in order to remain faithful, close to his flock until his death. He took this decision in full awareness of the grave consequences this choice would have had.

In June 1955, the welcome news arrived: “Today begins the registration for repatriation. I was told: ‘Citizen Bukowinski, we offer to repatriate you to the People’s Republic of Poland.’ I was glad to accept this decision… but, personally, I wanted to stay in the Soviet Union, so I became definitively a citizen of the Soviet Union.”

In 2004, John Paul II wrote to Cardinal Macharski, his successor as Archbishop of Krakow: “I am glad of the fact that the image of this heroic priest has not been forgotten. On the contrary, he goes on in the memories of many as a heroic witness to Christ and as a pastor of those who have suffered persecution for their faith and origin.”

Itinerant missionary

As a Soviet citizen, Fr. Bukowinski had permission to move throughout the Soviet Union. He gave up his job as night janitor, and from then on dedicated himself exclusively to the apostolate, with no need for permission from the authorities. On the outskirts of Karaganda, he bought a small house and transformed it into a chapel for the Polish community. Sadly, a year later the authorities closed it.

A little more than three years later, he was arrested, for the third time, because of his religious activity in Karaganda. He was accused of having built a church illegally, and of making propaganda to children and young people. He refused the help of a lawyer and defended himself in the trial, making an impression on his judges. As a result, he was given only three years of hard labor, instead of the usual ten. On release, he took up his pastoral work again. His solid faith and his unfailing trust in the Providence gave him the strength not to give in to persecution. He was sustained by the certainty that God had sent him to that place, and his presence was needed.

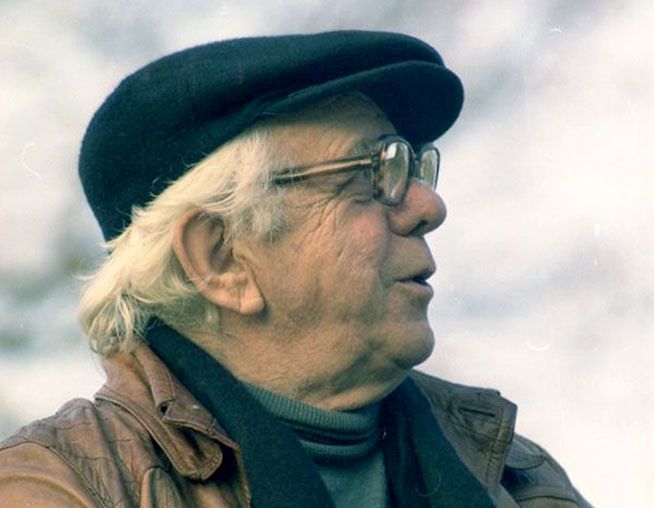

Fr. Wladyslaw made eight missionary journeys in places far from Kazakhstan; three times he went as far as Tajikistan. He returned to Poland three times, above all, for medical care; his health was weakened by the years in detention and the strenuous pastoral activity. There, he met Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, who took great interest in his apostolate in Kazakhstan.

He continued with his priestly mission in Karaganda until his strength was exhausted. On November 25, 1974, he celebrated Mass for the last time, received extreme unction and was taken to hospital: he died in Karaganda on December 3, 1974.

The news of his death spread quickly and there was widespread mourning. He was buried in the new cemetery on the outskirts of Karaganda in the presence of a huge crowd of mourners.

From that moment, Catholics visit his tomb regularly for prayer, realizing what Fr. Wladyslaw had predicted; that even his tomb would become an instrument of apostolate. In 1991, after the cemetery was flooded, his remains were transferred to St Joseph’s Church, and reburied near the external walls. In 2008, he was laid beneath an altar in the same church which, at the time, was the cathedral.

Admired by Pope John Paul

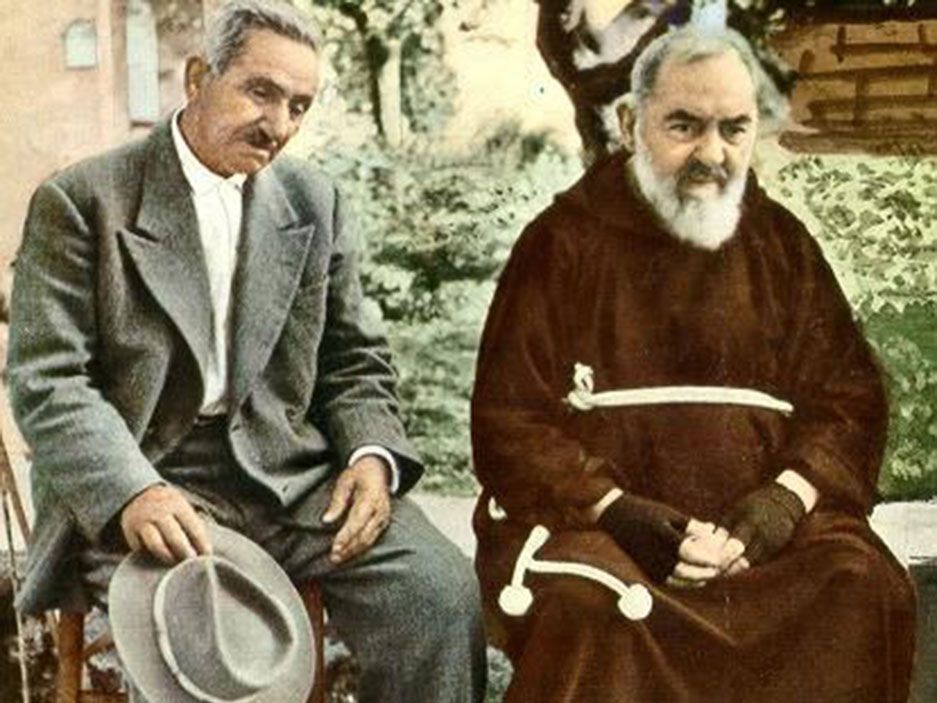

During his visit in 2001, John Paul II, expressing his affection for the many people in Kazakhstan who had suffered because of persecution, quoted Fr. Bukowinski three times during his visit to the presidential palace. “My first information about Kazakhstan came from Fr. Bukowinski who is well known here… It is a pity I cannot visit Karaganda and Fr Bukowinski’s tomb …”; at the Angelus: “I have always nourished a lively interest in your fate. The unforgettable Fr. Wladyslaw Bukowinski spoke a lot about you; I met him many times, and always admired him for his priestly fidelity and his zeal. He was very attached to Karaganda and he told me about all of you”; during the Mass with the clergy and religious, speaking of the seminary in Karaganda: “You want to dedicate it to the zealous priest, Fr. Wladyslaw Bukowinski who, during the hard years of communism, went on exercising his ministry in that city. He wrote in his Memoirs: “We were ordained not to spare ourselves but, if necessary, to give our lives for Christ’s sheep.” I myself had the fortune to know him and appreciate his deep faith, his words of wisdom, and his invincible trust in the power of God. To him and to all those who have spent their lives amidst hardships and persecutions, I wish to pay homage today in the name of the whole Church.”

His interior life was nourished daily with the Eucharist and by devotion to the Virgin Mary; this allowed him to perceive clearly and serenely the meaning of personal, social and ecclesial events. In the most difficult circumstances, his trustful abandonment to God’s will and unconditional fidelity to the Gospel were unyielding.

The diocesan process for canonization in Krakow lasted from 2006 to 2008, and the Congregation for the Causes of Saints recognised the juridical validity of this in 2009. In 2015, the same Congregation issued the decree recognising the priest’s heroic virtues. After accepting a miracle, obtained throught his intercession, Fr. Bukowinski was beatified on September 11. www.asianews.it