In Pre-Spanish society the mujer indigena enjoyed a singular status with equal rights in the family as well as in society. They actively participated in the economic, political and cultural life of the community and participated in all decision-making processes in all these areas. Moreover, in the religious field, she had the unique role of being the intermediary between the spirit world and the community in her role as the babaylan or priestess, an office reserved exclusively for women.

With the advent of Christianity and Western civilization into the islands, a strongly patriarchal system was imposed which had decidedly negative consequences on the role of women in society. Patriarchal society succeeded in alienating them from public life, public decisions, and public significance.

During the Spanish times convents and monasteries were not allowed to accept native vocations because the royal foundations were specifically created for “pious Spanish women and daughters of the conquistadores who cannot marry properly” without mention of native women. The mujer indigena could only enter the Third Order of the Religious Congregations as beatas. It was only in 1632 that a native beata of the Third Order of St. Francis from Pampanga was given an exception to join the monastery.

When the Spanish rule ended in the Philippines, the Church felt threatened by the coming of the Protestant missionaries, the rise of the indigenous Aglipayan Church and the prevalence of Masonry; and so the Church officials appealed to Europe and America to send religious missionaries to counteract these perceived threats.

Education

The Congregations that came in the early period of the American rule were all conscious that they were supposed to inculcate Christian Catholic values and so they all opened schools. The daughters of prominent families were educated by them and prepared them not only for being good wives and mothers but also for leadership in society.

For example, Corazon Aquino, the first woman President of the Philippines, studied in St. Scholastica’s College. The second woman president, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, graduated from the Assumption Convent. It is safe to say that many women leaders in all areas of endeavor studied in convent schools run by religious women.

The congregations of religious women lost no time in also addressing the health problems of the country. They established hospitals all over the country. Religious women established the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines, initiated the community-based health programs and held responsible positions in it.

Without religious women, parishes would be very limited in their services. Usually, one or two communities of Sisters take charge of activities in the parish such as parochial schools, organizing and training catechists and fielding them in different parts of the parish, and the building of basic ecclesial communities. They also arrange the liturgical services and some even take care of the housekeeping of the priest’s house and also of the seminary where there is one. They also take care of orphanages attached to the parish or diocese.

There are many social issues that have become the focus of the commitment of religious women especially that of women, i.e. discrimination of women in all areas of life, violence against women both domestic and societal, and the trafficking of women both local and international.

Many congregations have acquired farms to propagate organic farming and sustainable agriculture. Their schools have included environmental protection in the curriculum in all levels and encourage environmentally friendly practices with regard to waste management, anti-pollution, energy conservation, and reforestation.

Cloistered nuns bring the needs and sorrows of the world to God in their life of prayer. In spite of being cloistered, many contemplative communities have shown interest and concern for the burning issues of society.

During the martial law years 1972-1986, many religious women became aware of the injustices and oppression of the people and became actively involved in the struggle of the basic masses: peasants, workers, urban poor, and indigenous peoples.

Rise Of The Laity

The Second Vatican Council, convened in 1965, introduced radical changes in the life of the Church. Among the most significant is the change in the perspective of the Church as a Church in the world. This is the context of the rise of the laity in the Church.

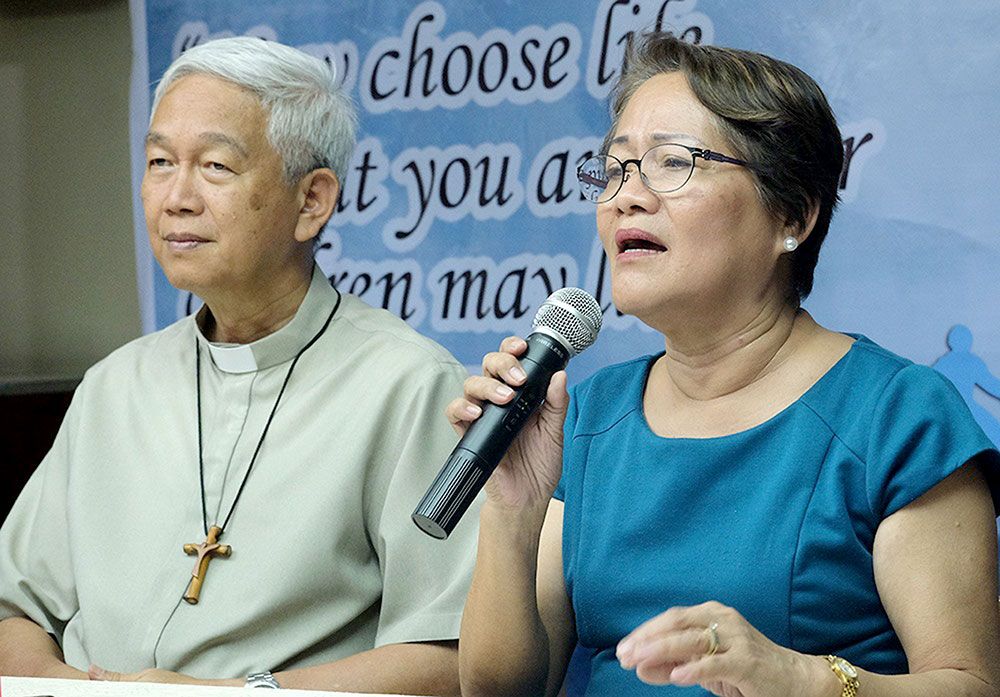

In the Philippines, the event that actually gave impetus to the rise of the laity was the Second Plenary Council of the Philippines (PCP II). In his address to the assembly of SAC directors in 2006, Cardinal Orlando Quevedo emphasized the role of the laity and especially women in the Church. He said: “Lay people must take the lead in social transformation. In particular, we shall consult a wide range of women’s experiences in different life situations and explore new possible roles of women in Church and society.”

With Vatican II, women could read the first and second readings, distribute Holy Communion and act as commentator during the Mass. Girls could be sacristans and Mass servers.

After PCPII, women started to join Church organizations which gave them opportunities for leadership and decision-making. They are not only active in Church-mandated women organizations like the Catholic Women’s League and the Mother Butler’s Guild but also in mixed organizations like Couples for Christ, Christian Family Movement, Christian Life Community, etc. However, leadership in these mixed organizations is still mainly in the hands of men.

Main Issues

I would like to end this piece highlighting what I consider to be the main issues women have to face in the Church:

1. Reproductive Health Law

The “Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012” which guarantees universal access to methods of contraception, fertility control, sexual education, and maternal care, will be a continuing bone of contention between women and the hierarchy in the Philippines.

2. Sexual Abuse by the Clergy

A serious problem in the Church which affects women, girls and, in some instances, young boys is the sexual harassment and abuse by the clergy. Since the priests cannot or will not assume any responsibility for the children they bring into the world, the responsibility and burden falls on the shoulders of the victims–the unwed, single mothers. In the Philippines, no priest has ever been imprisoned for his crime and is often just simply transferred to another parish where often the offenses are repeated.

3. Continuing Gender Inequality in the Church

There has been great progress in gender consciousness in the Philippines due to the strong women’s movement. In fact, many women-friendly laws have been passed, including a Magna Carta for Women. However, practice in the Church has not kept up with the progress of women’s empowerment in the wider society.

The Catholic Church still holds a conservative view of women. Church teachings on family life still emphasize the “obey your husband” dictum. Battered women are advised to stay in such a marriage so as not to have a “broken family.”

Moral theology still focuses on the “sins of the flesh” with a certain bias against women as “Eve the temptress.” The cult of virginity that prevails makes women who lose their virginity not through their fault feel like garbage.

In the liturgy, there is still a sexist tone addressing the assembly as “brethren,” praying for the salvation of “mankind,” and exhorting to love one’s “fellowmen.” The women are given minor roles in the liturgy, but they shoulder the more burdensome preparations behind the scenes and the “making order” after each celebration.

Although women are the most active in Church service functions and activities, they are deprived of participation in the major decision-making processes and are denied full ministry in the Church. Celibate priests continue, in fact, to make the rules and prescriptions governing marriage and family life. The structure is hierarchical and clerical, and women have no part in both.

4. Feminist Theology of Liberation

The women in the Philippines, both lay and religious, conscious of the continuing gender inequality in the Church, participated in the development of a Feminist Theology of Liberation from the perspective of Asian women within the Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians (EATWOT). Their avowed task is to deconstruct what is oppressive in religion and to reconstruct what is liberating. They have participated in national, regional and international conferences on feminist theology, delineated its methodology, defined its hermeneutics, and embarked on concrete projects like a Feminist Theology Journal. They are determined to see to it that the liberating factors in religion (Christianity) will somehow neutralize its oppressive aspects.