In February, the world watched in horror as large parts of southern Turkey and northern Syria were levelled by a devastating earthquake that killed upward of 40,000 people (as of mid-February).

Just one month later, Syrians, still recovering from the shock, marked the fact that their country has been involved in a civil war for 12 years. That is an entire generation of children who are reaching adolescence with no memory or experience of anything other than conflict.

For this reason, in Syria at least, the terrible earthquake was described as a tragedy within a tragedy, and Syria’s tragedy has been going on for too long.

Syria used to be known as a haven for Christians in the Middle East, where Islamic extremism was not tolerated and Christians and Muslims of different denominations lived in peace side-by-side. Freedom was heavily restricted by an authoritarian regime, but this was a price many were willing to pay for safety and stability.

One of the reasons the regime had no tolerance for Islamic extremism is that the ruling elite is itself from a minority, the Alawites, an off-shoot of Shiite Islam which makes up about 10% of the Syrian population.

The war began in 2011. The “Arab Spring” toppled regimes in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya. In Syria, however, the pro-democracy movement was soon hijacked by Islamist groups that thrived on the resentment in the majority Sunni community over being ruled by the Alawites.

At the time of the war, Christians also made up around 10% of the population in Syria. With no wish to be governed by the Sunni majority, most Christians tended to support the regime, even as they recognised its lack of respect for basic freedoms and human rights. In exchange, they got to live and worship in peace.

CIVIL WAR

The civil war changed all that. Many Sunni rebels identified Christians as being pro-regime and were therefore enemies. Things only got worse as the years wore on and rebels became increasingly Islamist in nature. The Islamic State began to expand, spreading terror in its wake, and at one point occupied a third of Syria and a third of Iraq, proclaiming a Caliphate and governing it with its own laws, police force, and even currency.

Hundreds of thousands of Christians suffered at the hands of the Islamic State. Those who could escape to the West, bringing the Christian population down to a fraction of what it once was in the country.

Over time, and with crucial support from Russia, the Syrian regime managed to defeat the rebels and drove them back to a pocket of territory around the city of Idlib, near the border with Turkey. The Turkish government intervened to protect the rebels there and fighting eventually ceased, although formal peace was never achieved.

HOPELESS SITUATION

If the COVID pandemic affected the whole world, in countries like Syria, where hundreds of thousands of people were already living in camps or in poverty, the situation was almost hopeless.

What is more, Western sanctions against the Damascus regime made financial and material aid more difficult to organize. Most Syrians were essentially left to fend for themselves while the economy took a dive, unable to resist the general downward trend of the rest of the world.

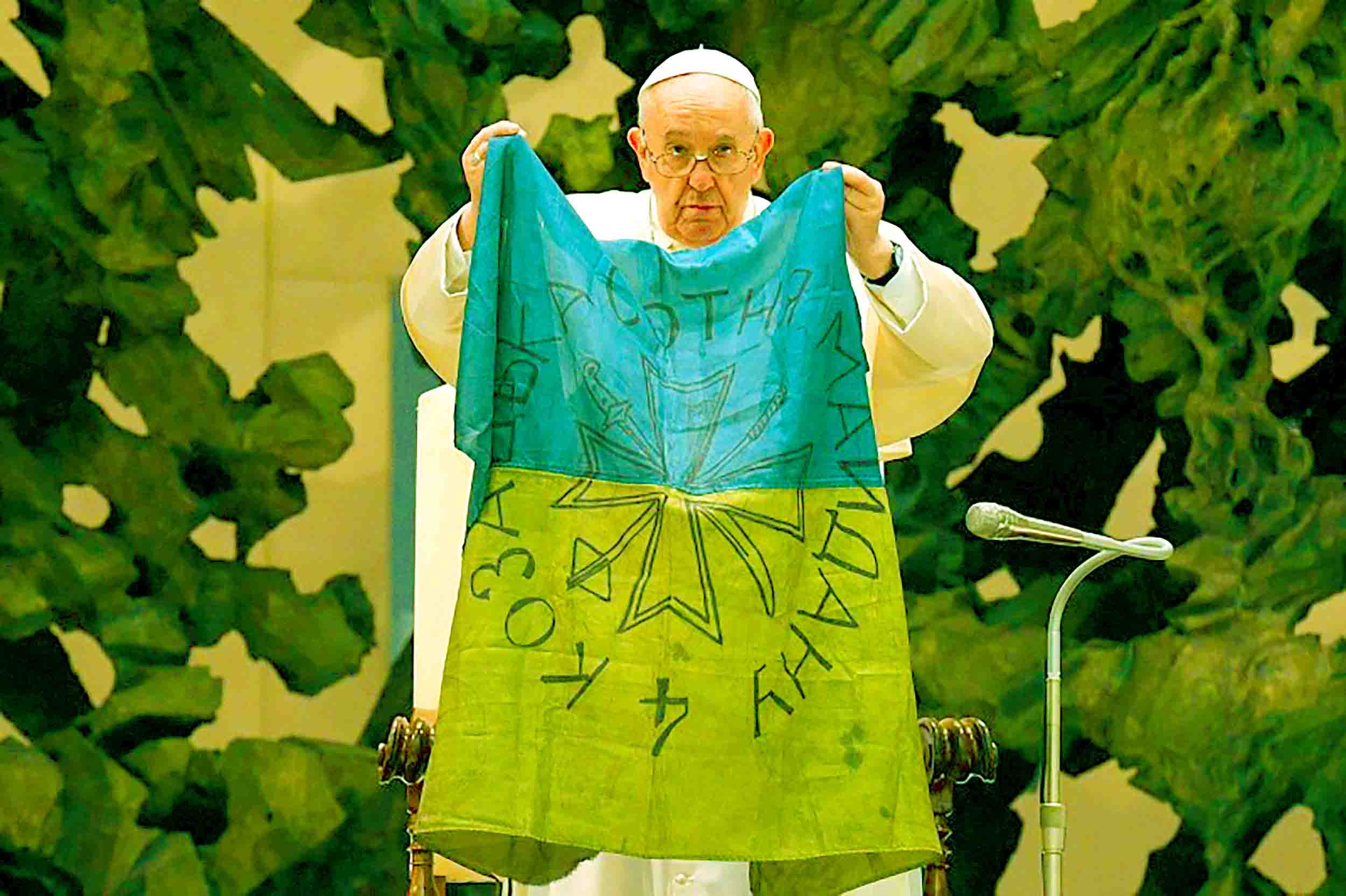

As the rest of the world began to return to life as normal, Syria once again found itself in a difficult position. The collapse of the Lebanese financial system directly affected Syria, leading to a very serious economic crisis, and Damascus’ main ally, Russia, decided to invade Ukraine.

What the Kremlin seemed to think would be a three-day special military operation to topple the Government in Kyiv turned into a drawn-out war in which Moscow suffered several serious setbacks. The assault on Kyiv failed dramatically and by the end of 2022, a successful Ukrainian counterattack had pushed Russia back out of several regions in Eastern Ukraine that it had managed to occupy.

Now it was not only Damascus that had to deal with sanctions, but also Moscow, meaning that support from Russia for Syria became very unreliable at best, and the few Western organisations still interested in helping the long-suffering Syrian population found it difficult to do so for fear of being punished for violating the sanctions in place.

By this time, the only Christians left in Syria were those who were unable to emigrate or those who consciously wanted to stay behind and keep the ancient Christian community in that country alive. Many of them saw their homes and possessions vanish on February 6, as the earthquake destroyed large parts of cities such as Beirut, Lattakia, Homs, and Hama.

Unsurprisingly, the few international aid workers found them in a state of utter depression, with some saying that they felt as though they were being punished for having remained in their country.

Nonetheless, there were faint signs of hope. One representative of the pontifical charity Aid to the Church in Need said she was witnessing demonstrations of unity and solidarity that she had not seen since the war began. Local clergy spoke of the courage and energy of the Christian youth who came together to clear rubble and help care for the thousands of people who–afraid to return to their homes–sought shelter in the Church buildings. Ecumenical prayer services were organized. In Aleppo, for example, Catholic and Orthodox bishops joined together to form an emergency response team of engineers to survey the houses of all the Christians in their communities to see if they were safe to return to or not.

DEMOCRATIC EXPERIMENTS

In most of Syria, unless they were drafted into the army, Christians did their best to remain apart from conflict and not publicly take sides in the civil war. There was one exception, however. Many Christians living in northeast Syria decided to form armed militias to defend themselves from growing threats.

This region has a large population of Kurds, and the Christians, Kurds, and representatives of other ethnic and religious groups created the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and a local governing structure, the Autonomous Administration of North East Syria (AANES).

This structure, a sort of state within a state, represents one of the most interesting democratic experiments in the Middle East over the past years. All the major ethnic groups are represented in the different political posts, and women and men are present in equal numbers. The SDF even has exclusively female contingents, such as the Kurdish Women’s Protection Units (YPJ), and the Christian Bethnahrain Women’s Protection Forces.

The AANES began by being opposed to the Damascus regime, but quickly realized that it had a more immediate and dangerous enemy in the Islamic State. Through great sacrifice and courage, the SDF fighters managed to keep the IS at bay and then, slowly but surely, and with vital Western intelligence and air support, drive the group back until they finally dealt a death blow to its territorial ambitions in March 2019.

However, the Kurdish influence in the AANES is unacceptable to Turkey, which considers the group to be equivalent to the PKK, a Kurdish militant organization operating in Southern Turkey that has been labelled as terrorist.

Turkish leader Erdogan vowed not to let the Kurds and their allies set up an autonomous state next to Turkey’s borders and ordered his troops to northeast Syria, occupying towns and villages and killing or driving out civilian populations, including many Christians.

At the moment, it is not clear if Bashar al-Assad will allow the democratic experiment in the AANES to continue, but since his main allies, Russia and Iran, are otherwise engaged at the moment, and especially after the devastation caused by the February earthquake, he may prefer to continue the live-and-let-live policy that has been in place for several years.

Meanwhile, Syria stands as a witness to the worst that the Arab Spring brought to the Middle East. While Tunisia managed to shake off its dictatorship and has settled into a relatively stable democracy, in Egypt, the army deposed an Islamist President who had been democratically elected but provoked much unrest in the nation, with attacks against Coptic Christians multiplying as the audacity of fundamentalists grew. It is little consolation that Yemen and Libya are perhaps as bad or worse off than Syria, 12 years later.

One thing is certain. Western sanctions are doing nothing to change the regime, and there is no guarantee–in fact quite the opposite–that regime-change at this time would improve the lives of the Syrian people. Syria already needed help before the earthquake. It needs help even more now.