The world’s largest democracy still tolerates manual labor in cleaning its filth. Instead of constructing effective and sustainable sewage system, the Indian government itself patronizes undignified manual labor that claims the lives of the country’s poorest citizens.

In a country of 1.3 billion people, it is difficult to identify who among them work as manual scavengers, one of the menial tasks delegated to the Dalits or the “Untouchables” under India’s caste system. Dalit women clean dry latrines – toilets bereft of the modern water flush system – with bare hands and carry buckets of human wastes atop their heads to dispose of at remote locations. What adds insult to injury is the measly compensation they get from doing such an undignified work. A toilet cleaner gets only 50 U.S. cents a month for upkeeping one dry latrine daily. In order to earn U.S.$5 every month, a woman needs to clean at least 10 toilets every day.

Dalit men are worst off for they are usually contracted to clean sewer lines or septic tanks. They submerge themselves in manholes without wearing any protection or using any equipment and step on waist-deep filth consisting of feces, dead rodents and garbage. More fortunate in earnings than their female counterparts, Dalit men get paid between US$4.50 and US$7.50 for a day’s work – that’s if they manage to come out of the cesspit alive. Just recently, three manhole-cleaning sanitary workers choked to death in Madhapur, Hyderabad, after inhaling poisonous methane gas while working on the sewers. A cab driver who tried to rescue the scavengers likewise failed to come out of the manhole alive.

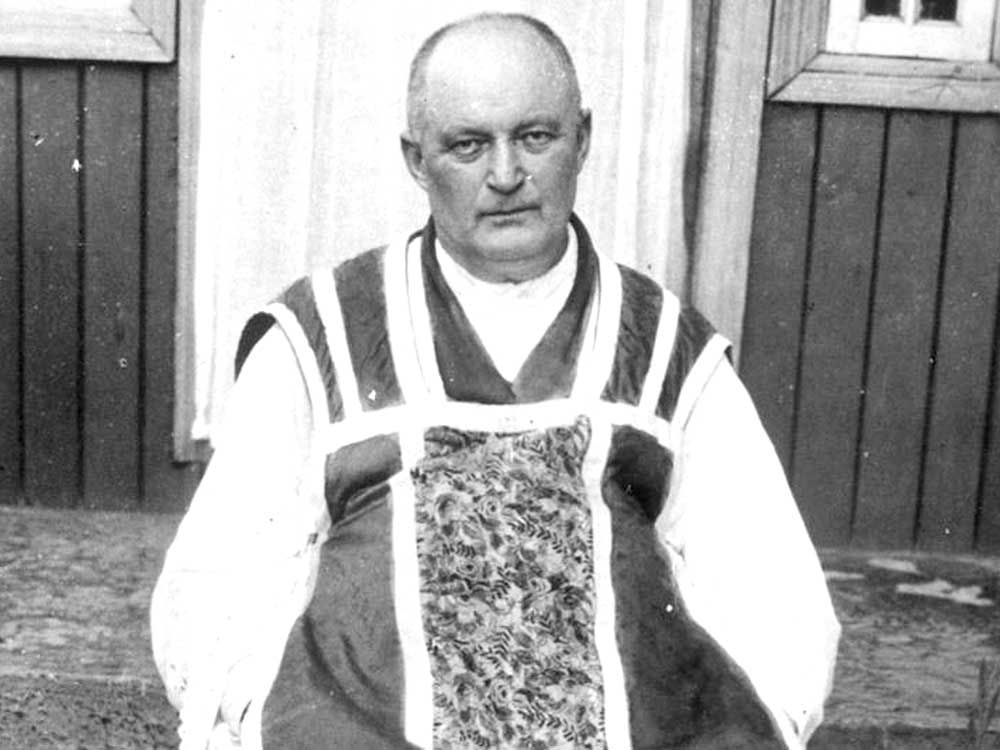

The recent deaths due to manual scavenging were reported only weeks after a Dalit was conferred Asia’s version of the prestigious Nobel Peace prize. For advocating the eradication of the abominable practice and helping manual scavengers pursue other forms of livelihood, Bezwada Wilson is one of the six recipients of this year’s Ramon Magsaysay Award.

Trapped in the caste

Wilson was born to a Dalit family on February 16, 1966. His parents worked as manual scavengers to earn a living and, like his siblings, Wilson was subject to discrimination for being part of a scavenging family. While he refuses to do the menial job as means of livelihood, Wilson said he grew up getting offers to work as such simply because of caste-imposed prejudice against Dalits.

“Circumstances under the caste system makes it difficult for Dalits to survive,” Wilson said. “Everybody looks down on us and treats us as subhumans. So under those circumstances, we have to struggle and fight for every step we take. But when we do, the upper caste reminds us that we are ‘untouchables.”

Living in a Dalit community in Kolar Gold Fields township in Karnataka state, Wilson grew up with poor people who work either as manual scavengers or street sweepers to survive. In fact, it was due to manual scavenging that Wilson’s parents were able to afford to send him to school to pursue education. His degree in Political Science from the Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Open University in Hyderabad is a fruit of his parents’ undignified work. But Wilson knew it doesn’t have to require the same arduous path for other Dalits to lead better lives. He believed the status quo should not persist and that manual scavenging should cease to exist.

“No human being deserves to be carrying human excreta and disposing it by hand. I cannot tolerate seeing it. I could not digest it. No humane society can bear this indignity,” he said.

Degrading work

Wilson said manual scavengers are the most marginalized of the Dalits. Aside from being underpaid for doing an undignified work, they are prone to health hazards for doing menial work without protection. The stench of the dry latrines or the sewers is so awful that sanitation workers need to consume alcohol to bear it. “They told me they needed to drink alcohol because if not, they cannot do this kind of work,” he recalled.

At one point, Wilson entertained the idea of committing suicide after being made aware of the plight of his fellow Dalits and yet unable to improve the situation. At 19 years of age, he felt trapped and useless, unable to tolerate the humiliation his family, relatives and neighbors face for working as manual scavengers. But as young as he was, Wilson aspired to challenge the status quo. Days of meditation led Wilson to seek heaven’s guidance: “Let me have some courage to tell the world that what is happening here is inhumane.”

Fueled by his anger and frustration, Wilson formalized his crusade in 1993 when he founded Safai Karmachi Andolan (SKA). The movement was set up when Wilson initiated the filing of a public interest litigation case before India’s Supreme Court where he named all states, union territories and government offices of railways, defense, judiciary and education as violators of the 1993 Prohibition Act banning usage of dry latrines and employment of manual scavengers.

Crusade throughout India

Due to the heightened clamor to stop the age-old industry of manual scavenging, the SKA movement expanded to various states and led a nationwide march in 2010 to push for the demolition of dry latrines.

In 2013, the SKA successfully lobbied for a new law that forced the government to provide rehabilitation support for scavengers, to grant scholarship to scavengers’ children and to give vocational training for scavengers’ daughters to help them become eligible to take on more decent jobs. In 2015, the SKA led a 125-day bus journey across 30 states to mobilize local Dalit communities against the inhumane trade. The small movement grew into what is now a national network of 7,000 members across 500 districts and over 25 states in India. Due to Wilson’s crusade, half of the estimated 600,000 scavengers in the country were liberated from their caste-imposed profession and made aware of their right to choose a dignified occupation.

If not for SKA’s continuous advocacy work, the government would not have initiated devising schemes that support scavengers to pursue other livelihood options. Wilson said the government now gives 40,000 Indian rupees (U.S.$595) to each individual who decides to stop working as a scavenger. After four to five months, the former scavenger can propose a livelihood project to the government and request a loan to support it. “The government provides loans worth one to 15 lakhs (1 lakh = 100,000 rupees = US$1,492). If someone wants to buy a buffalo, he will only get one lakh; the one who wants an auto rickshaw could get as much as four lakhs. The government will give according to what they choose provided the loan amount is not more than 15 lakhs,” Wilson explained.

But, unfortunately, not everybody is receiving government support. “There are too much corruption and bureaucratic hurdles, that is why the majority are not getting it,” Wilson pointed out. “Apparently, the eradication of manual scavenging is just not about making the law or designing a scheme. Our advocacy also requires us to force our government to function. We are not fighting just to reclaim our dignity and self-respect; we are fighting for democracy to survive, the government to function, the judiciary to get active, and the media to be involved.”

Getting media attention

After winning the Ramon Magsaysay Award this year, Wilson admitted that his anti-scavenging crusade is getting more media attention than ever before. But he lamented the excessive focus on his life instead of the underlying issue that propelled him to receive the prestigious citation. “Media is focusing on me too much. It should focus on the manual scavengers, their fight and struggle. They should have more coverage in media than me,” he said.

Nevertheless, Wilson recognizes the leverage he got from taking home the distinction. Before being given the citation, he used to wait before meeting government officials in line with his advocacy. But after the announcement of the Ramon Magsaysay Award winners on July 27, Wilson said the officials would come out to welcome and escort him to their offices. “A lot of people have neglected and ignored us many times before. Now, it is difficult for them to ignore us after I received the Ramon Magsaysay Award because it is a well-recognized citation in Indian society. The government cannot ignore us, and more people are listening to and taking us seriously,” he said.

Because of his recognition, Wilson said the SKA can push for its anti-scavenging advocacy more powerfully. He expressed confidence that their long march is going to end very soon, particularly in 2019, when the SKA expects to completely demolish all dry latrines across India. “By 2019, there should not be a single woman cleaning dry latrines anywhere in the country,” he confidently said. “After then, the next phase of SKA’s work is to save the men who risk their lives in cleaning septic tanks and sewer lines.”

Wilson said it is not enough that the government is providing financial aid of 10 lakhs for each death related to dangerous sanitation work. “We don’t want the government’s money. We need the government to protect our life. These deaths are political murders perpetuated by the state because the government has not taken any political action or setup proper sanitation practices to stop the loss of lives,” he stressed out.

A 50-year-old bachelor, Wilson dedicates his life to the crusade. “My fight is not just about the eradication of manual scavenging,” he clarified. “It is a fight for democracy, fraternity and restoration of dignity, self-respect, and equality. Democracy should reflect everybody’s aspirations, not just that of the dominant caste or the small portion of the population.” But if he dies, Wilson is confident that thousands of Dalits will carry the torch on his behalf. “There is no doubt that there are thousands of people thinking just like me in India. Anyone of them can take the crusade forward. They have understood my agony and witnessed my sacrifices. That is more than enough to inspire them to push forward and make the change.”