From my African perspective, the first thing the encyclical has done is to change the way we perceive ourselves. Pope Francis named something for us that we have often felt, but had not the approved Catholic language to express: a natural spirituality.

We are inextricably part of nature, and nature is part of us. This permits us not only to foster a deep fellow-creature solidarity with our natural and human environment, but also encourages us to have a deep love for the non-human part of God’s creation.

In the final chapter of the encyclical, Pope Francis writes about an ecological spirituality, encouraging us to pray for the earth, and in union with all of creation: God has placed a covenant between humans and the world, so we can find joy and peace in our surroundings.

Because the Earth is sacred in this sense, we need a sincere conversion to a new lifestyle in tune with our Earth, and yet keeping our eyes on the world that endures forever. Finally, Our Lady exercises Queenship over the whole of creation, and not just over human beings.

Pope Francis is endorsing the ancient traditions which include Biblical images and parables, and most famously the spirituality of Saint Francis of Assisi in which everything that lives and breathes gives praise to God.

So, has the encyclical actually made a difference in the world? We need to remember that an encyclical is like a charter. It sets an agenda, or opens a process, a bit like the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations.

A Step In A Process

Laudato Si’ is one step in a process where all of humanity is re-evaluating its relationship with our common home, both natural and man-made. Within the Catholic Church, this re-evaluation goes back some 40 years, when Pope John Paul II wrote in Laborem Exercens about “the growing realization that the heritage of nature is limited and that it is being intolerably polluted.”

Francis says that we have to match our language with our actions. That is why in the momentous year of 2015, in which he published Laudato Si’, and the Paris Climate Change Convention was signed, he went to the United Nations twice, to make sure that the whole world knew the Church’s stance on the ecological crisis. He was at the General Assembly in New York in September, and in November he spoke at the UN offices in Nairobi.

For the past seven years, I’ve been reflecting on environmental ethics with students from all around Africa and some parts of Asia. Over time, I have noticed a growing awareness among the students of ecological problems in their countries. They are identifying the problems more readily and coming up with suggestions of what the church might do about deforestation, municipal waste, water pollution, overfishing, agricultural fertilisers, desertification, etc. The students (mostly seminarians) are seeing that this is a legitimate sphere of activity of the church, and I attribute this consciousness to Laudato Si’.

Importantly, in the last five years, the Catholic Church has also become more visible in the overall picture of environmental concern. In the spirit of service of the Second Vatican Council’s Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the World Today (Gaudium et Spes 89) “the Church [is] clearly present in the midst of the community of nations both through her official channels and through the full and sincere collaboration of all Christians.”

It is not just the hierarchy negotiating at high-level discussion. But ordinary Catholics are involved in clean-up operations in the town, at our rivers, and on the beaches. Members of the Churches can be found demonstrating with their fellow citizens, and demanding that our governments take serious and practical measures to reduce global climate change. Christian students are boycotting classes in the Friday climate strikes, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with Muslims, Hindus and people of no faith at all.

Ecological Conversion

Certainly this visibility is an indication of our ecological conversion. Individually, we are taking our environment seriously. But obviously larger social structures are not changing at the same pace.

People are still suffering from the terrible effects of pollution, hazardous working conditions, depletion of natural resources, and for generations, we will be dealing with the effects of global climate change. This is not something that can be repaired overnight. Have Catholic business people changed their practices? Have our governments actually enforced regulations, rather than just paying lip-service to their concern for the environment at the international level. When was an important industrialist last punished for environmentally destructive practices?

Pope Francis strongly criticizes the “throwaway culture” which is almost imposed on us by global industrial production. In order to survive, international industries have to be constantly selling “newer, bigger, better, faster, brighter” products, and convincing us that we need them. We know it’s propaganda. We know it’s not true. But when have we deliberately chosen not to “upgrade” our phone, or tablet, laptop, motor bike, or car or clothes, even if we could afford it? Have we consciously taken note of what has happened to our previous model? Where has it ended up?

The ecological conversion the pope is suggesting involves education–not just for our children, but more specifically for ourselves as adults. We need to make informed choices regarding our lifestyle.

Education doesn’t have to come from reading heavy books. I get a lot of my information from credible films like A Plastic Ocean and An Inconvenient Truth. These fill me with horror, fear, disgust, or pity. Emotions like these can be the starting point for my ecological conversion, my decision to tread more lightly on the earth. The example that I give to children of living within the means of the planet will be repeated as they copy my behaviour. Indeed, I have to embody the title of the famous Club of Rome book of the 1970’s: There are Limits to Growth.

We can’t expect any encyclical to say everything. As any document is written within its particular time and space and set of historical circumstances, so the response is also a fruit of its historical contingency. Laudato Si’ incorporated a lot of the scientific and economic understanding of its time and applied it to the wellbeing of the planet and the people living on it. But these change. For example in the age of Covid-19 with the shutdown that is being imposed all over the world, we are developing a new understanding of economics, and the vulnerabilities of the people most marginal to the mainstream economy, food and medical supplies. People will be writing about this economic collapse for decades to come.

Similarly, science moves on. The concerns of 2015 are not the same concerns as 2020. Or at least, they are experienced and expressed differently, in both the scientific and popular spheres. In 2015, the encyclical focussed on six of the nine so-called “planetary boundaries” which were cutting-edge science at the time.

Heightened Awareness

Over the intervening years we have seen a heightening popular awareness of plastic pollution–both on land and in the oceans. Terms like “microplastics” and “persistent organic pollutants” have become mainstream. The damage done by drinking straws, cast-off fishing tackle, fast-food containers and cutlery has been brought to the attention of Joe-in-the-street. In some countries like Kenya, where I live, single-use plastic bags have been banned, as a small but significant contribution to the reduction of plastics in the environment.

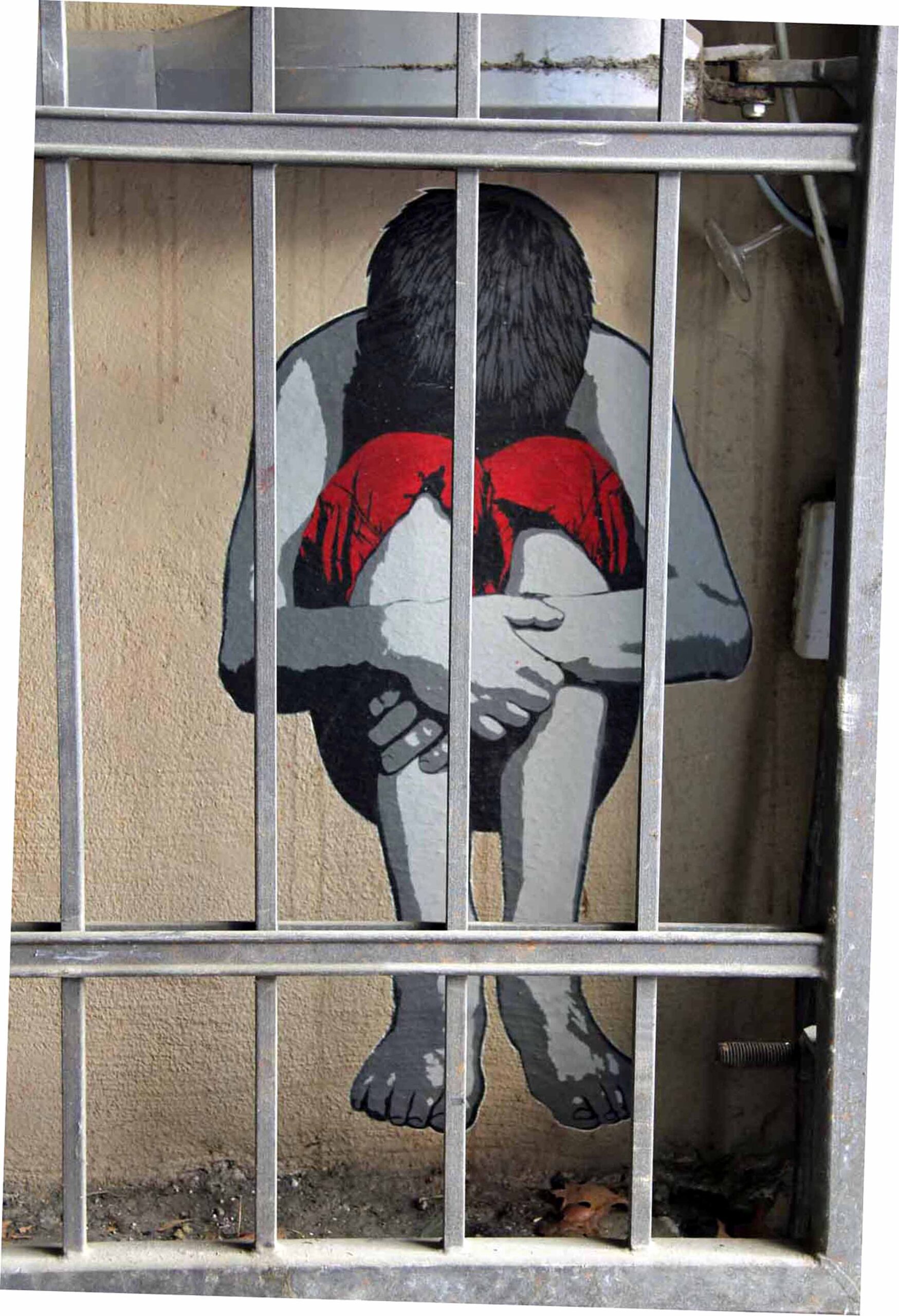

Europe has seen the largest waves of migration since the end of the Second World War, and the Mediterranean Sea has become a veritable cemetery of people escaping wars in Syria, Yemen, Libya and other parts of Africa. The phenomenon of climate migrants has continued to grow. Social movements have grown. For example, schoolchildren, fed up with the inaction and complacency of their parents’ generation towards global climate change, have begun weekly “climate strikes,” and rallied behind Greta Thunberg. “Extinction Rebellion” is a more in-your-face protest group that did not exist when the encyclical was written.

Scientists have been warning about the proliferation of “nanoparticles” which are being produced with very little control, and which have the potential to alter life in unforeseen ways. These are used in cosmetics, medicines, detergents, agriculture, etc., and their producers have no idea what damage they are capable of, and where they will end up. A lot of this is cutting-edge science. But it hasn’t been thought through to the very end.

Finally, in laboratories around the world, scientists are experimenting with life forms, “playing God” as they do genetic manipulations. I guess we’ll never know whether the coronavirus responsible for Covid-19 was man made or occurs naturally. But what cannot be disputed is that it has reminded us that we are inextricably tied to other living and non-living elements of our planet. Everything is interrelated. And humans cannot dominate forces that are so much greater than we are.

We should be humble in the face of even the tiniest microbe that can cause havoc in our lives. Genesis 1 tells us that God created all things good, and humans “very good.” Laudato Si’ is reminding us to live up to our divine vocation.