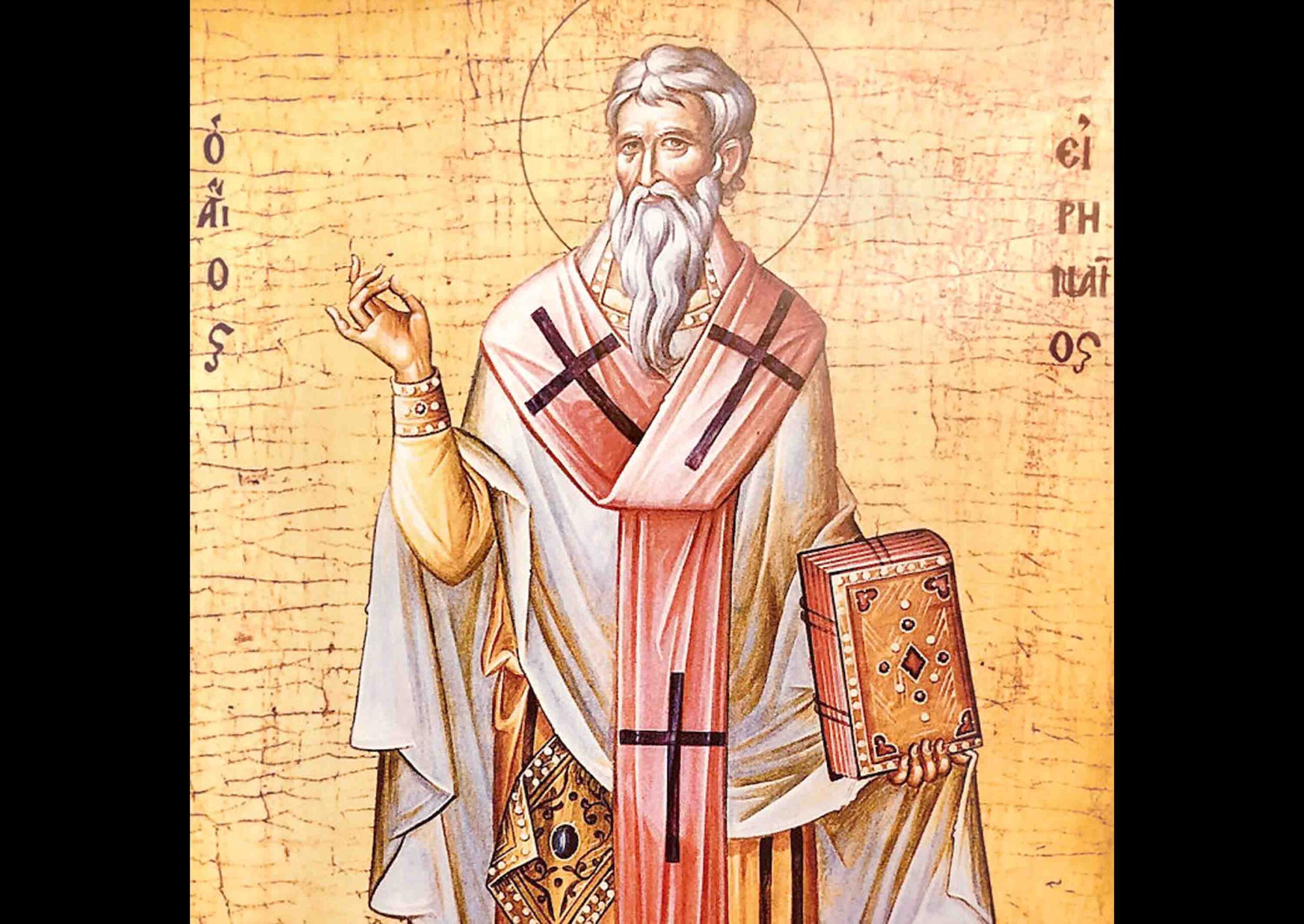

Jerome was, next to Origen, the greatest biblical scholar of the early Church. He was born in 346 AD at Stridon, on the borders of Dalmatia and Pannonia. His parents were Christians, so the young Jerome grew up with both a general knowledge of the Bible and some appreciation of its place in the Church’s life.

They were also comparatively well-to-do, which meant that he was free to indulge his natural intellectual interests and his ‘great ardour for learning’ without the necessity for earning a living. He wrote: “Almost from the cradle, I have spent my time among grammarians, rhetoricians and philosophers.”

As a young man, he went to Rome to sit at the feet of the celebrated grammarian Donatus. Here he made his formal profession as a Christian and was baptized. He also embarked on the study of the Greek language and Greek literature. To this period must also be assigned the beginnings of his very considerable library, to which he was continually adding, and which he carried about with him wherever he went.

The most decisive influence on Jerome’s later life was his return to Rome (382–385 AD) as secretary to Pope Damasus I. There he pursued his scholarly work on the Bible and propagated the ascetic life. The summer of 386 AD found him settled in Bethlehem. Here Jerome lived, except for brief journeys, until his death.

FOR MORE THAN A MILLENNIUM

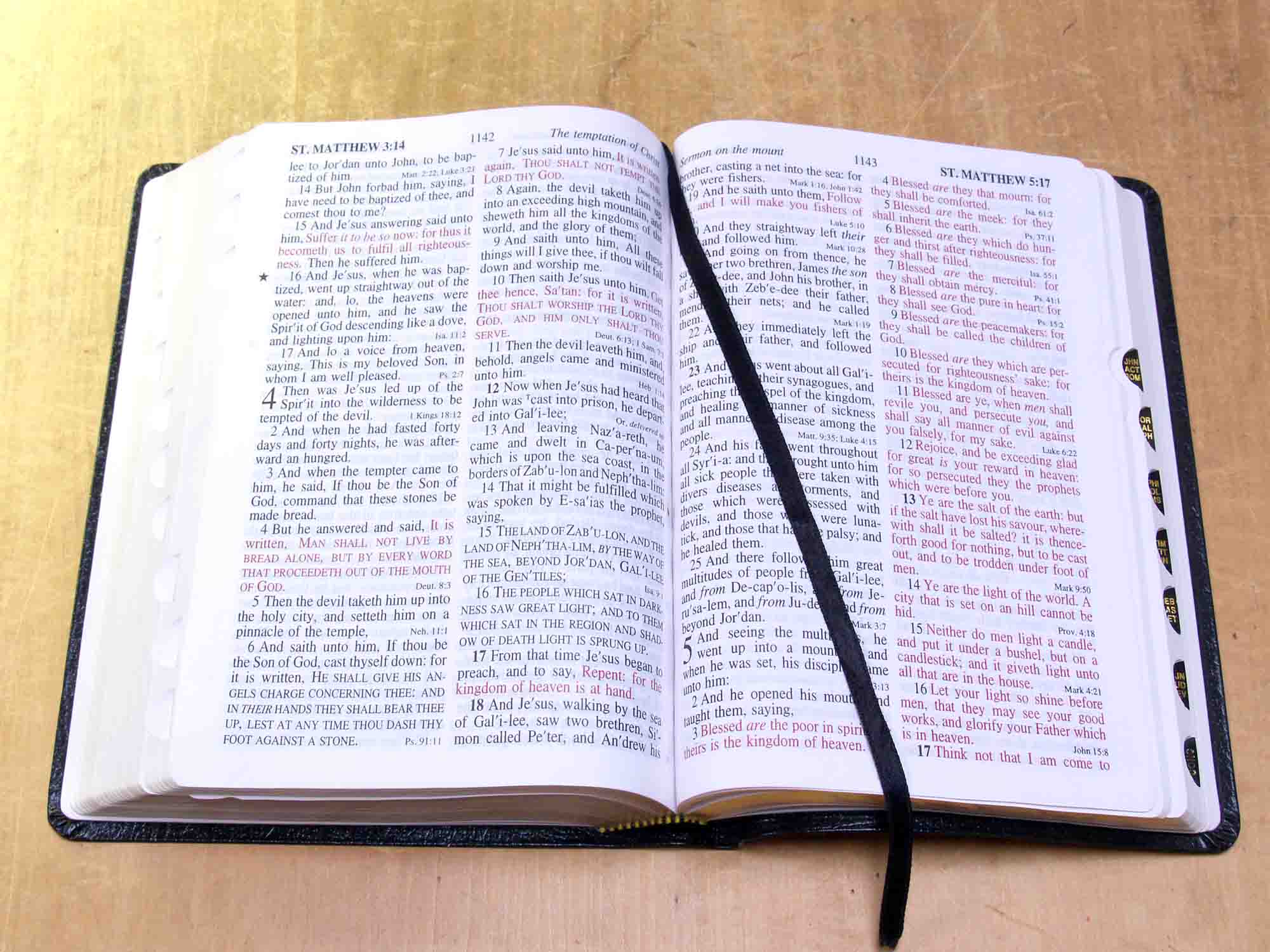

Perhaps the greatest figure in the history of Bible translation, he spent three decades creating a Latin version that would be the standard for more than a millennium. This is how he writes to a friend about the importance and the beauty of studying the Holy Scriptures: “I entreat you, dearest brother: does not dwelling among these things, meditating on them, knowing and seeking nothing else seem to you to be the dwelling place of the heavenly kingdom on earth? I do not wish that you be offended in the Sacred Scriptures by the simplicity and almost banality of the words. They have been set down in this manner either through the fault or the skill of the translators so that they might more effectively instruct the uneducated multitude.

Thus, in one and the same sentence, the learned person might hear one thing and the unlearned another. I am not so impudent and dumb as to state that I know these things and that I gather on earth the fruits of those things whose roots are in heaven. But I have the desire and show that I am making an effort. Although I refuse to be a teacher, I offer myself as a companion. The one who asks receives, the one who knocks is admitted and the one who seeks finds. Let us learn on earth the knowledge of things which will remain with us in heaven.”

IGNORANCE OF SCRIPTURES IS IGNORANCE OF CHRIST

Again he writes: “I therefore am paying back what I owe to you, Eustochium, and to him, Pammachius: please, obey the commands of Christ who says: “Search the Scriptures” (John 5:39), and, “Seek, and you will find” (Matthew 7:7), so that I may not hear along with the Jews: “You go astray, since you know neither the Scriptures nor the power of God” (Matthew 22:29). If, according to the Apostle Paul, Christ is the power of God and the wisdom of God, then whoever is ignorant of the Scriptures is ignorant of God’s power and wisdom. To be ignorant of the Scriptures is to be ignorant of Christ” (Commentary on Isaiah, prologue).

This last sentence is how Jerome is mainly remembered. It is remarkable not only because of the power of his concise statement but also because it helps us understand that knowledge of the Scriptures is a vital way of uniting ourselves to Christ, who is the “Word made flesh.”

Jerome is remembered for his extensive erudition, especially his understanding of the classics, the Bible, and Christian tradition. He was a learned scholar, a deep thinker, a sound traditionalist and not a speculative theologian, more competent as editor than as exegete. His career was a turbulent combination of scholarship and asceticism, and his correspondence is an exciting source for the historian, Scripture student, and theologian.

His influence has been far-reaching and profound, particularly in the early Middle Ages, primarily through the Vulgate, the Latin version he translated. The name Vulgate means “popular.” His importance also extends through his work as an exegete and humanist and because he transmitted much of Greek thought to the West.