The missionary journeys of Blessed Junipero Serra have caught the imagination of historians since they sometimes envisioned him to be a miraculous character. Father Junipero, with a single companion, once arrived at his convent on foot, without provisions, having crossed a vast desert area. The Brothers welcomed the two in astonishment, believing it impossible that men could have crossed such a great stretch of desert in this naked fashion.

The Superior asked them where they came from, and said the mission should not have allowed them to set off without a guide and without food. He marveled at how they could have gotten through alive. But Fr. Junipero replied that they had been most agreeably entertained by a poor Mexican family on the way.

At this, a muleteer, who was bringing in food for the Brothers, began to laugh, and said there was no house for twelve leagues, nor anyone at all living in the sandy waste through which they had come. The Brothers confirmed him on this. Fr. Junipero and his companion, Fr. Andreas, together with some of the Brothers and the scoffing muleteer, went back into the wilderness to prove the matter. There, they found three tall trees and the dead trunk to which the ass had been tied.

But the ass was not there, nor any house. Then the two priests sunk down upon their knees on that blessed spot and kissed the earth, for they perceived that it was the Holy Family that entertained them. Fr. Junipero remembered that, after prayers, when he bade his hosts goodnight, he had stooped over the little boy in blessing, and the child had lifted his hand, and with his tiny finger made the cross upon Fr. Junipero’s forehead.

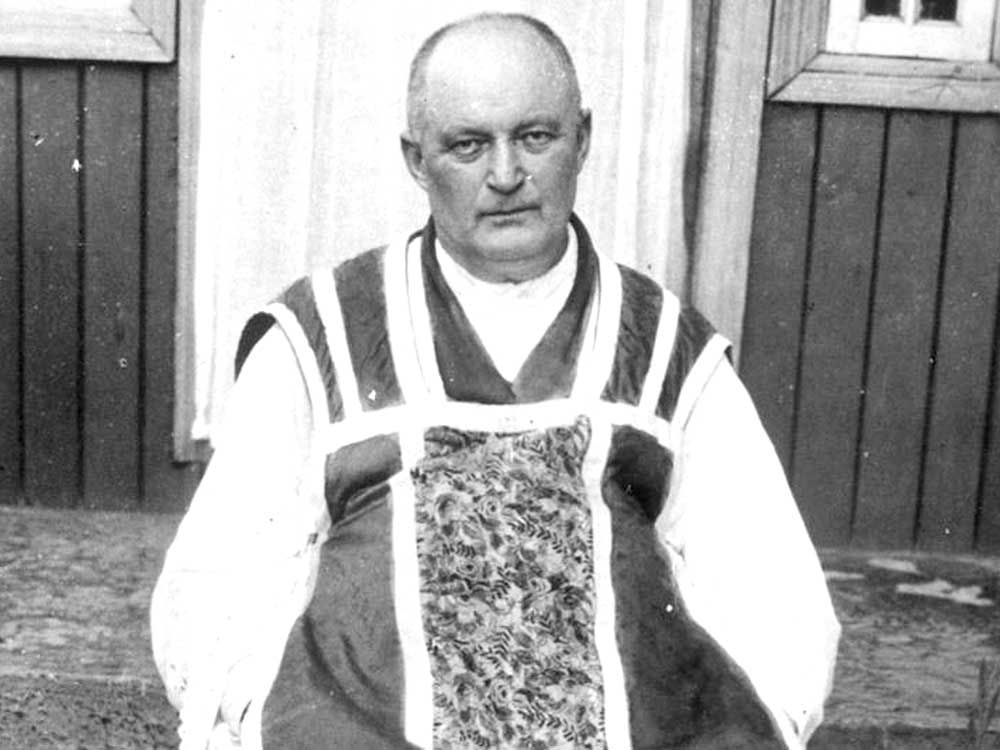

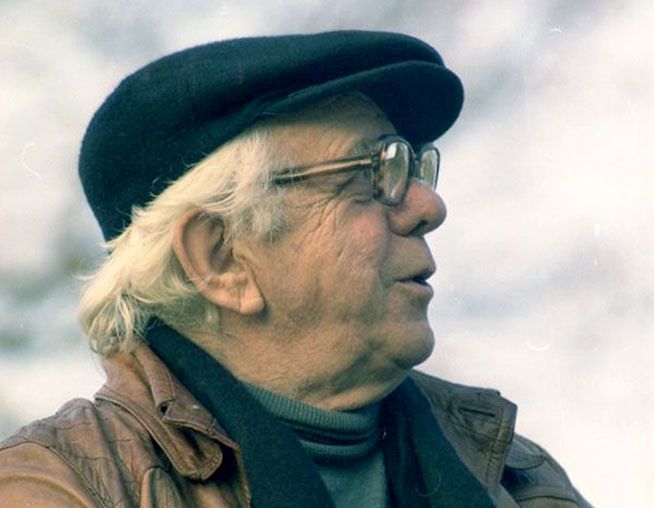

A REAL MISSIONARY

Blessed Junipero was so popular because he was spontaneously taken as a missionary. On the one hand, he really enjoyed being with native peoples who were not baptized, the reason he had come to the New World. For instance, one of the most emotional days of his life was in a place in Baja California where a group of natives came out of the woods and presented themselves to the priest. This was the first time in his life that he had personally encountered a large group of unbaptized Indians.

He was overwhelmed. In his diary of the journey from Loreto in Baja California to San Diego in 1769, he wrote: “I kissed the ground and thanked God for giving me what I have longed for so many years.” It was really a tremendously emotional experience for him. After 19 years in America, he was finally going to get to do what he came to do: preach to the unbaptized.

On the other hand, the native peoples he met perceived that he really wanted to be there with them: he really enjoyed being with native peoples because he felt that his identity as a missionary, which was the most important thing for him, was in such way fulfilled. The Indians really did like Fr. Junipero and they were very fond of him. They kept calling him “Padre Viejo” or old father. He kind of liked that. He was considerably older than most of the other Spaniards or Mexicans the natives were encountering. He was also shorter and more frail than most of them.

In December 1776, he was traveling through the Santa Barbara area, and there was a huge rainstorm. So the small party that he was with had to leave the beach where they were traveling and go up to the foothills because the waves were coming in. They got bogged down in the mud. Suddenly, and out of nowhere, a group of Chumash Indians appeared. They picked Fr. Serra up and carried him through the mud so that he could continue his journey. They stayed with him for a couple of days, and he enjoyed trying to teach them to sing some songs. That was the kind of thing that he just loved.

A SUCCESSFUL SCHOLAR

Serra was born as Miguel José Serra y Ferrer to a family of humble means, in Petra, Majorca, Spain. On November 14, 1730, he entered the Order of the Franciscans and took the name “Junipero” in honor of Saint Juniper (Ginepro), who had also been a Franciscan and a companion of Saint Francis.

For his proficiency in studies, he was appointed lector of Philosophy before his ordination to the Catholic priesthood. Fr. Serra was considered intellectually brilliant by his peers. Prior to his departure for the Americas at age 27, he was assigned by his superiors to teach philosophy in professorial status to students at the Convento de San Francisco. He received a Doctorate in Theology from the Lullian University in Palma de Mallorca, where he also occupied the Duns Scotus chair of Philosophy.

In 1749, Fr. Serra applied for the missions of the New World, but once he arrived there, he was still assigned to teach. While traveling on foot from Vera Cruz to the capital, he injured his leg in such a way that he suffered from it throughout his life, though he continued to make his journeys on foot whenever possible. At last, at his own request, he was assigned to the Indian Missions of Sierra Gorda, some thirty leagues north of Querétaro. He served there for nine years, part of the time as superior, learned the language of the Pame Indians, and translated the catechism into their language.

Recalled to Mexico, he became famous as a most fervent and effective preacher of missions. His zeal frequently led him to employ extraordinary means in order to move the people to penance. He would pound his breast with a stone while in the pulpit, scourge himself, or apply a lighted torch to his bare chest.

In 1768, Fr. Serra was appointed superior of a band of 15 Franciscans for the Indian Missions of Baja California. The Franciscans took over the administration of the missions on the Baja California Peninsula from the Jesuits after King Carlos III ordered the latter forcibly expelled from New Spain on February 3, 1768. Fr. Serra became the “Father Presidente.” On March 12, 1768, he embarked from the Pacific port of San Blas on his way to California.

The next year, the Spanish governor decided to explore and found missions in Alta (Upper) California. This was intended both to Christianize the extensive Indian populations and to make them citizens of the Spanish empire. Early in the year 1769, Fr. Junipero accompanied Governor Gaspar de Portolà on his expedition to Alta California.

As he had founded a mission in Baja California, he founded the first nine of 21 Spanish missions in Upper California from San Diego to San Francisco. He began in San Diego on July 16, 1769, and established his headquarters near Monterey, California, at Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo. He remained there also as “Father Presidente” of the Alta California missions.

THE FOUNDER OF SPANISH CALIFORNIA

The missions were primarily designed to convert the natives. Other aims were to integrate the neophytes into Spanish society, and to train them to take over ownership and management of the land. As head of the Order in California, Fr. Serra not only dealt with church officials, but also with Spanish officials in Mexico City and with the military officers who commanded the local garrisons.

Franciscans saw the Indians as children of God who deserved the opportunity for salvation, and would make good Christians. Converted Indians were segregated from Indians who had not yet embraced Christianity, lest there be a relapse. Discipline was strict, and the converts were not allowed to come and go at will.

Serra wielded this kind of influence because his missions served economic and political purposes as well as religious ends. The number of civilian colonists in Alta California never exceeded 3,200 and the missions with their Indian populations were critical to keeping the region within Spain’s political orbit. Economically, the missions produced all of the colony’s cattle and grain and, by the 1780s, were even producing surpluses sufficient to trade with Mexico for luxury goods.

During the American War of Independence (1775–83), Fr. Serra took up a collection from his mission parishes throughout California and the money was sent to General George Washington.

Fr. Serra received the title of Founder of Spanish California.

THE WAY TO SAINTHOOD

During the remaining three years of his life, Fr. Serra once more visited the missions from San Diego to San Francisco, traveling more than 600 miles in the process, in order to confirm all who had been baptized. He suffered intensely from his crippled leg and from his chest, yet he would use no remedies. He confirmed more than five thousand people who were Indian neophytes converted within 14 years, starting from 1770.

On August 28, 1784, at the age of 70, Fr. Junípero Serra died at Mission San Carlos Borromeo. He was buried there under the sanctuary floor. Pope John Paul II beatified him on September 25, 1988. On that occasion, the Pope said: “Blessed Junipero Serra sowed the seeds of the Christian faith amid the momentous changes wrought by the arrival of European settlers in the New World. It was a field of missionary endeavor that required patience, perseverance, and humility, as well as vision and courage.”

During Fr. Serra’s beatification, questions were raised about how Indians were treated while he was in charge. The question of Franciscan treatment of Indians first arose in 1783. The famous historian of missions, Herbert Eugene Bolton, gave evidence favorable to the case in 1948, and the testimony of five other historians was solicited in 1986. On January 15, 2015, Pope Francis announced that, in September, he hopes to canonize the 18th century Spanish Franciscan as a part of his first visit to the United States. (Fr. Junipero Serra will be canonized on 23 September 2015 in Washington D.C.)

A FRANCISCAN LIFESTYLE

Fr. Serra’s religious conviction found in him a congenial mental disposition. He was even-tempered, sober, obedient, zealous, kindly in speech, humble and quiet. His Franciscan habit covered neither greed, guile, hypocrisy, nor pride. He sought no quarrels and made no enemies. He wanted to be a friar, and he was one in sincerity. Probably few have approached nearer to the ideal perfection of a Franciscan lifestyle than he. Even those who think that he made great mistakes of judgment admire his earnest, honest and good character.

Iris Engstrand, chair of the Department of History at the University of San Diego, described Fr. Serra as much nicer to the Indians than even to the governors. He didn’t get along too well with some of the military people. His attitude towards them was: ‘Stay away from the Indians.’ “I think you really come up with a benevolent, hardworking person who was strict in a lot of his doctrinal positions, but not a person who was enslaving the Indians, or beating them, ever….He was a very caring person and forgiving. Even after the burning of the mission in San Diego, he did not want those Indians punished. He wanted to be sure that they were treated fairly.”

Besides extraordinary fortitude, his most conspicuous virtues were insatiable zeal, love of mortification, self-denial, and absolute confidence in God. His executive abilities have been especially noted by non-Catholic writers. The esteem in which his memory is held by all classes in California may be gathered from the fact that Mrs. Stanford, a non-Catholic, had a granite monument of him erected at Monterey. A bronze statue of heroic size represents him as the apostolic preacher in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. In 1884, the Legislature of California passed a resolution making 29 August of that year, the centennial of Fr. Serra’s burial, a legal holiday.

The setting of his extraordinary adventure as well as that of all the missionaries in the Southwest of the U.S.A. is the subject of the classic book of American literature, written by Willa Cather: Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927). She explains how she discovered it: “The longer I stayed in the Southwest, the more I felt that the story of the Catholic Church in that country was the most interesting of all its stories. The old mission churches, even those which were abandoned and in ruins, had a moving reality about them; the handcarved beams and joists, the utterly unconventional frescoes, the countless fanciful figures of saints, no two of them alike, seem a direct expression of some very real and lively human feeling.

They were all fresh, individual, firsthand. Almost every one of those many remote little adobe churches in the mountains or in the desert had something lovely that was its own. In lonely, somber villages in the mountains, the church decorations were somber, the martyrdom bloodier, the grief of the Virgin more agonized, the figure of Death more terrifying. In warm, gentle valleys everything about the churches was milder. I used to wish there were some written account of the old times when those churches were built, but I soon felt that no record of them could be as real as they are themselves. They are their own story.” Blessed Junipero Serra, in his person and in his story, represents all of this.