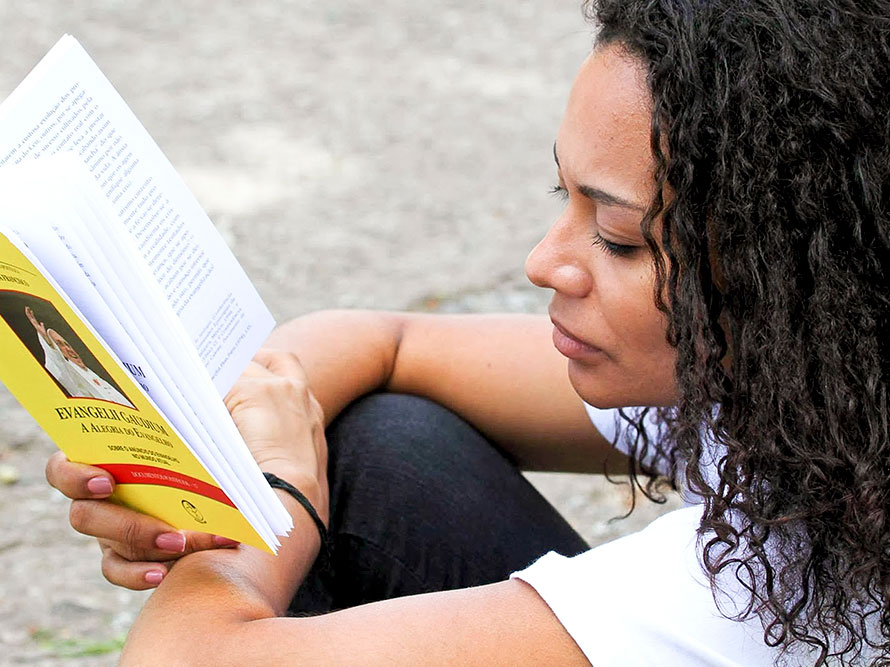

Consider the Parable of the Good Samaritan: “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell into the hands of robbers, who stripped him, beat him and went away, leaving him half dead… [A] Samaritan while travelling came near him; and when he saw him, he was moved with pity” (Luke 10: 30, 33).

Pope Francis uses this parable as the lens through which he evaluates fraternity and social friendship in his encyclical, Fratelli Tutti (FT). In the Christians’ economic dealings, abuse of others cannot occur; we cannot behave like the brigands in the Parable of the Good Samaritan, who beat, who steal (FT n. 75). These robbers represent the worst of humanity.

The Acts of the Apostles describes the lives of the first Christians after Jesus’ Ascension, as they began birthing the dynamics of the Early Church. The manner in which they undertook their economic activity stands as the ideal Christian model: “The whole group of believers was united, heart and soul; no one claimed for his own use anything that he had, as everything they owned was help in common… None of their members was ever in want, as all those who owned land or houses would sell them, and bring the money from them, to present it to the apostles; it was then distributed to any members who might be in need” (Acts 4: 32, 34–35).

The Church Fathers elaborated upon and developed the Church’s social teaching from very early on in its existence. Perhaps there was no other way but to do this since the faith spread rapidly and Christians were to be found in so many parts of society. As the 2nd century African Church Father, Tertullian, noted: “We [Christians] are but of yesterday, and we have filled every place among you–cities, islands, fortresses, towns, market-places, the very camp, tribes, companies, palace, senate, forum–we have left nothing to you but the temples of your gods” (Apology 37).

Pope Francis points out that a number of the Church Fathers argued for the common ownership of material goods (FT n. 119). St. Basil radically argued that being born with no possessions, no person is entitled to own any possessions–viewing private ownership as akin to robbery. In a similar vein of thought, St. John Chrysostom argued: “Not to share our wealth with the poor is to rob them and take away their livelihood. The riches we possess are not our own, but theirs as well” (FT n.119).

St. Ambrose echoes this idea, for all that we have belongs to God; and St. Gregory the Great, in his Pastoral Rule (n. 21), said that in giving the needy what is needed, we simply return to them what properly does not belong to us.

For the Church Fathers, the theme of need comes across as important. St. Basil, for example, argued that if all people utilized only what they needed then there would be enough for all people. Moderation is key. If we truly have care for our brothers and sisters, we will need only what we require to suffice, as excessiveness results in others lacking given that there is always only a limited supply of goods.

This leads me to contemplate why some of the Fathers were so against the private ownership of goods, holding literally to the example described in Acts. Perhaps the radicality of their critique was not so much against the holding of goods, but the manner in which the goods were utilized to the exclusion of others.

Capital And Labor

In 1891, Pope Leo XIII issued a revolutionary encyclical letter that became foundational to Catholic Social Teaching. Rerum Novarum (On capital and labor) gave Pope Leo the opportunity to speak “… on the condition of the working classes” (n. 2), who the Pope saw as enduring both “misery and wretchedness” in their daily lives as a consequence of economic exploitation (n. 2).

Pope Leo considered the rights and obligations of the employer and the employee. While the workers have the responsibility of working hard and faithfully, the employers should not enslave employees for they are persons of dignity, not to be exploited for personal gain or to be burdened unjustly with too much labor, and they must earn a just wage (n. 20).

The position that employees should earn justly leads us directly back into the issue of ownership of property because a just wage implies the usage of wages for the sake of living. Pope Leo endorses that all are entitled to possess private property (n. 6). It is in the usage of property that Pope Leo hearkens back to the earlier teachings of the first Fathers of the Church and of St. Thomas Aquinas in the Summa Theologica: “… [W]hen what necessity demands has been supplied… it becomes a duty to give to the indigent out of what remains over.”

The obligation to care for those who do not have from the excess that one does have points to the basic moral principle of the ‘common good,’ that is, the shared conditions within a society that enable all people to live in accordance with their potential fulfillment (Rerum Novarum n. 34; Catechism of the Catholic Church 1995 n.1906).

Catholic moral teaching must always uphold the foundational premise that all human life is sacred (Catechism of the Catholic Church n. 2258). The gauge that indicates the morality of any economic activity is whether or not an action enhances the fundamental sacredness of human life through the actualization of the common good. Oftentimes, when the economy is distorted, human beings are consciously maligned (FT n.18, 20), as a few financial oligarchs greedily increase their bank accounts, or fund their lavish, ostentatious lifestyles.

Economics Of Solidarity

Pope Francis’ diagnosis of the ever-widening gap between rich and poor rests in what he considers to be the conscious distance between the self and the common good: “[T]he gap between concern for one’s personal wellbeing and the prosperity of the larger human family seems to be stretching to the point of complete division between individuals and the human community…” (FT n. 1906).

We–all who engage in capitalist-like economic actions–seem to forget the Christian law, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Mt 22: 39). Rather, the love of ourselves and our families has displaced the love of others.

To share the excess that we do not need rather than piling it up in our bank accounts is the challenge. We need to be reminded of the command to love our neighbors. We need to be reminded of the virtue of solidarity.

To be in solidarity with another person or group of people means loving, acting, and serving for the sake of the good of that person or those people. In a world where we are constantly told by financial planners that we should store up as much as possible, solidarity will not be easily accepted. Yet, it is a deeply human way of being.

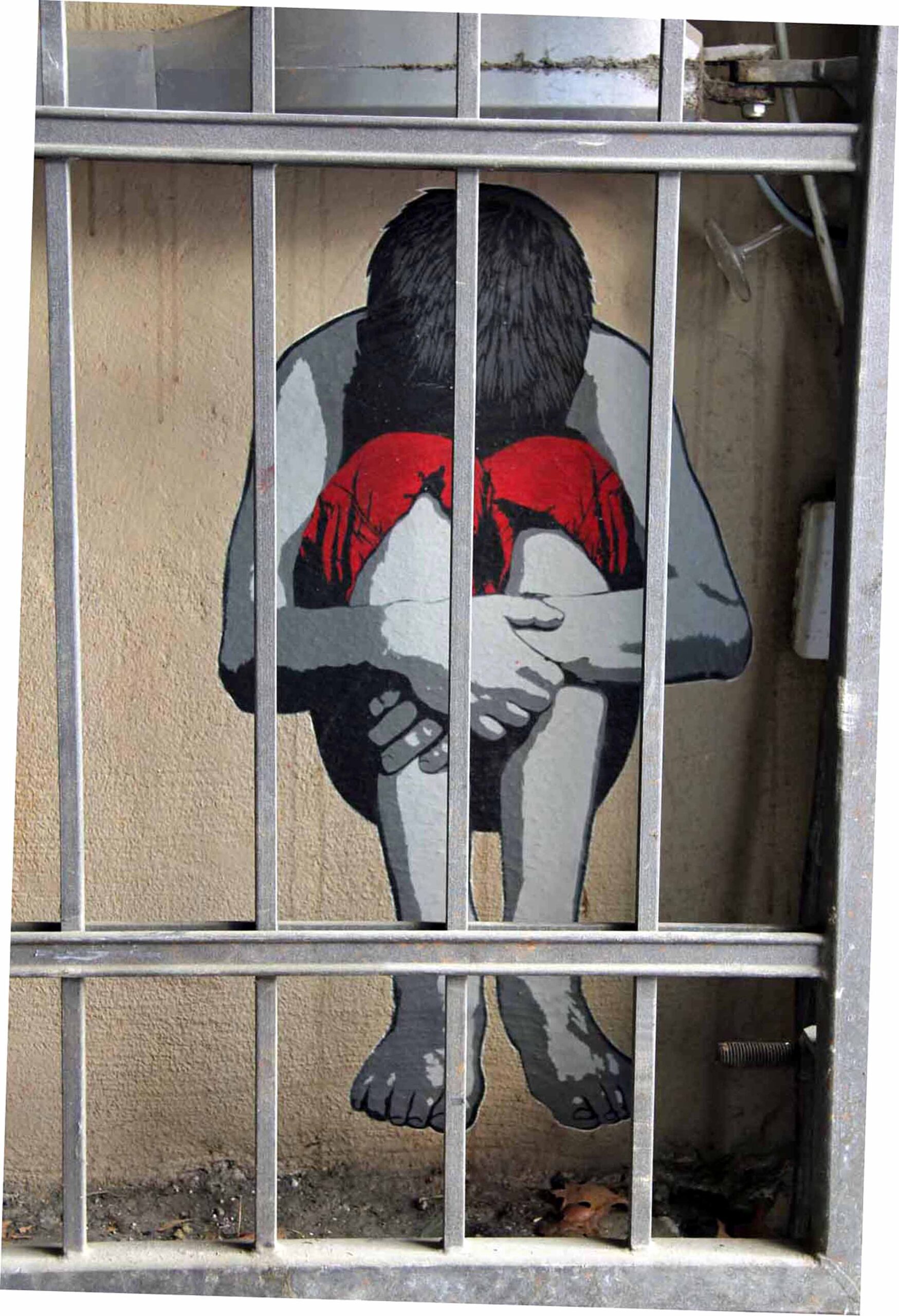

“… [Solidarity] means thinking and acting in terms of community. It means that the lives of all are prior to the appropriation of goods by a few. It also means combatting the structural causes of poverty, inequality, the lack of work, land, and housing, and the denial of social and labor rights. It means confronting the destructive effects of the empire of money…” (FT n. 1906).

The invitation to consciously embrace and live out an “economics of solidarity,” implies that economic activity is placed second, whereas the good of others is given primacy because of all people’s innate dignity (FT n. 168). In this sense, “[t]he economy should work for people,” people should not work for the economy.

Perhaps, however, the challenge that rests before the invitation to an “economics of solidarity” can be taken up, is the surrendering of our own “consumerist individualism” (FT n. 222), which is thoroughly incompatible with Jesus’ command to love others as we love ourselves.

Pope Francis bids the Christian faithful to embrace a truly Christian way of economics: “In the name of the poor, the destitute, the marginalized and those most in need, whom God has commanded us to help as a duty required of all persons, especially the wealthy and those of means…” (FT n. 285).