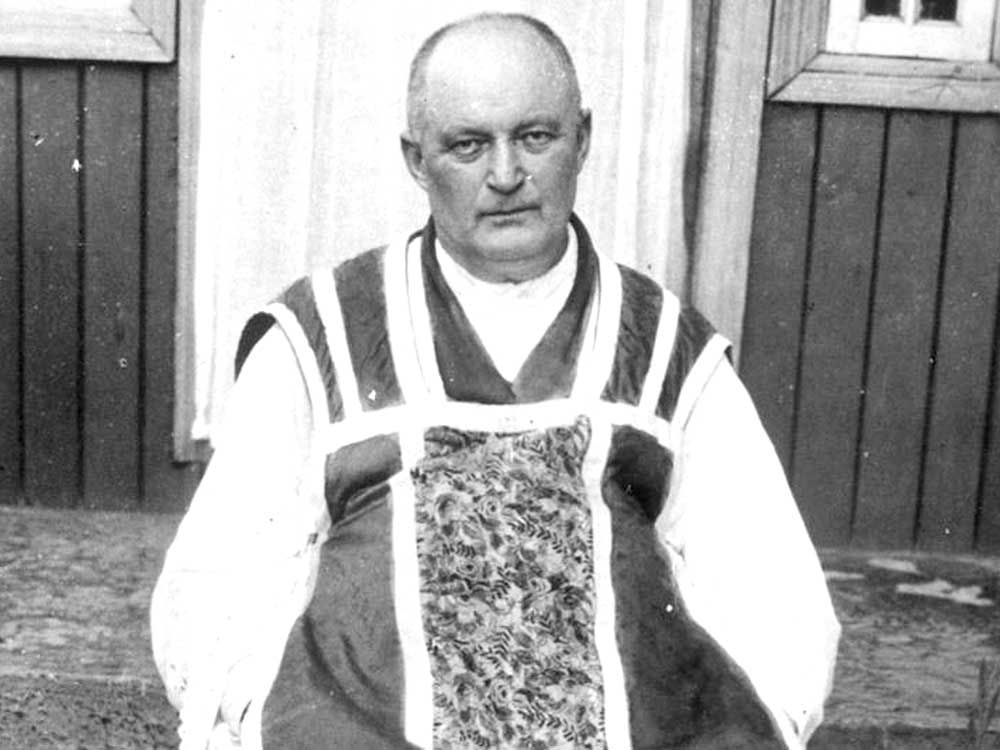

Deep in the heart of rural Bangladesh, home to some of the most impoverished people on earth, lies the Kailakuri Health Center, an initiative of Dr. Edric Baker, a New Zealander who devoted 35 years of his life to creating a unique formula of providing health care for the impoverished of that populous country. His impetus can be summarized as “health care to the poor by the poor.”

Fairly recently, however, the Christian presence in the health care of Bangladesh suffered a great loss: Dr. Edric Baker died on September 1, 2015 at the age of 74. He passed away rather suddenly, almost two years after being diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary hypertension, an incurable illness. He had neglected his health because of his daily commitment to his institution: the Kailakuri Health Care Project, of which he was the founder and remained the Project Director and Medical Coordinator until shortly before his death.

What troubled him in the end was also the fact that he didn’t see his hope to have a doctor as a successor and carry on his life’s work come to fruition. He was surrounded by people he loved and who loved him. Over the last few days of his life, he had a rough time breathing but nobody expected his passing on so soon.

Right up until the last hour, he was giving orders and making phone calls. That was just like him. The word “retire” was not in his vocabulary. Within half an hour of his passing away, his room became full of caring people whom he had helped over the years.

After the news of his death broke out, hundreds of villagers, many in tears, went to the center to pay their last respect. It was a country in mourning. It is hard to describe how much he was loved and respected. Up to the moment of his death, he was never once left alone. Later, during the wake, a local Mandi woman sang songs, people read from the Koran, others wept, and others stood silently keeping a vigil. During his burial, he was still surrounded by those he loved and who loved him.

People came from all over Bangladesh, some arriving in the night. Most refused beds offered to them for rest and preferred to tell stories of their time with Dr. Edric late into the night. Even in death, he managed to bring different communities and cultures together: Christian, Muslim, Hindu, rich, poor, Bangladeshi and Badashees (foreigners); all worked side-by-side to fulfill his final wishes. By the evening, he was laid out on a table in the waiting room. Hundreds of people came to say their goodbyes and show their appreciation.

By morning, many visitors and staff had not slept but no one minded. Intense activity began early. By ten o’clock, the whole compound was full of people. He was laid in his coffin and carried to the church, which doubles as a school, beside the hospital. As the Mass was progressing, hundreds waited outside and then followed his casket back to his house. He had made it clear to the staff that he wanted to be buried at the back of his house, underneath his veranda.

As he was being laid to rest, two lines of people formed surrounding his house and extending all the way out to the road. Slowly, everybody gave their final farewells and each person sprinkled earth over his grave. At the end of the day, the staff was happy that they were able to fulfill two, out of three, of his final wishes. His first wish was to take his last breath at Kailakuri. His second wish was that he be buried at the vicinity of the Kailakuri Health Care Center. His third wish was that the hospital continues to stay open and operational long into the future. For this, it is essential that a doctor would volunteer as Dr. Edric did. At the time of his death, this had not yet happened.

A universal chorus of praise

Speaking to Asia News, Most Rev. Ponen Paul Kubi, Bishop of Mymensingh, remembered him as “a simple man, who had a major role in our country and diocese. We shall remember him for many years. For all of us, he was an example of how we can sincerely take to heart caring for people.”

In 2014, Dr. Edric was awarded Bangladeshi citizenship in recognition of his outstanding contribution to the nation. Local and international media often reported on his work. He was popular and highly respected among Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists and, of course, Christians.

Many of those at the funeral recall how he won the hearts and minds of people through his love. People were struck by his kindness and saw that his goodness was due to his Christian faith. He spread the Gospel through his service. “Dr Edric Baker’s death is a great loss,” said Rajia Sultana Shully, a Muslim woman. “Doctors from Bangladesh should learn from him how to treat patients in a conscientious way.”

“He gave meaning to life in serving the poor. May his soul rest in peace,” said Hanif Sanket, a director and anchorman at the state-owned Bangladesh Television (BTV). Sanket produced a documentary, in 2011, on Dr. Baker’s work which raised his profile and led the Bangladeshi government to grant him Bangladeshi citizenship. The Catholic physician “loved our country more than we did even though he was a foreigner,” said Masum Billah, one of his patients. Hasima, another patient, shares that sentiment. “I have only heartfelt love and respect for him,” she said.

Dr. Baker was a “saintly figure” and a great missionary, according to American Holy Cross Father Eugene Homrich, parish priest of the local St. Paul’s Catholic Church. “To help and understand the poor people, he lived like the poor. He used to eat little, sleep on the floor and wore simple clothes. Truly, he was a holy man, both in his personal and professional life,” said Father Homrich.

A progressive engagement

Dr. Edric Baker was born in New Zealand in 1941. He was from a rich, noble family of practicing Catholics. As a young man, he went to medical school and obtained his MBBS degree from Otego Medical College at Dunedin, New Zealand, in 1965. At that time, the Vietnam War was building up. In 1968, Dr. Edric volunteered to work with the New Zealand surgical team in Qhi Nhon, the provincial capital of Binh Dinh Province in what was then South Vietnam. The surgical team worked at the provincial hospital and attended to civilian casualties.

It was there that Dr. Edric said he learned his first lesson. “After several hours of traumatic war surgery on a patient who made full recovery, I saw him come back three months later to die of dysentery. That was the first step in my awakening,” he recounted. That was to say that what the poor needed most was elementary health care.

From the New Zealand surgical team, Dr. Edric transferred to a highlands mission hospital established in Kontum by Dr. Pat Smith. This served the ethnic minority hill tribes, known as the Montagnards. Kontum, near the Ho Chi Minh trail, was a volatile part of the country where, at times, the expatriate hospital staff were evacuated. On returning after one of these occasions, Edric was struck by how the local, totally untrained staff, had managed to keep the hospital running. This awoke in him a vision of health services for the poor by the poor.

Here, he was challenged to think about provision of health services for the poor and the marginalized. He became very much aware that, for the poor in most countries, health services do not exist. These experiences are the foundations of Dr. Edric’s original approach to the health care of the poor who do not have the means to pay for their health care or live in far-flung, isolated regions which are plagued by lack of qualified medical personnel.

In the meantime, the situation deteriorated in the Vietnam highlands and Dr. Edric ended in a communist prison for four months. He may well have spent the rest of his life in Vietnam had he not been deported by the communists after his imprisonment. Back in New Zealand, he set about equipping himself for a lifetime of service to the poor. Over the next few years, he obtained Diplomas in Tropical Medicine, Tropical Child Health and Obstetrics. He obtained experience by working in hospitals in Papua New Guinea and Zambia.

Services for the poor by the poor

By the early 1980s, he was ready to embark on what turned out to be his life’s work: developing health services for the poor by the poor. In 1979, he went to Bangladesh, one of the most desperately poor nations on earth. Under the auspices of the Church of Bangladesh, he proceeded to Thanabaird in the remote north of the country. Starting from scratch, he taught literacy and numeracy before training local people to become “barefoot medics” for the church’s clinic.

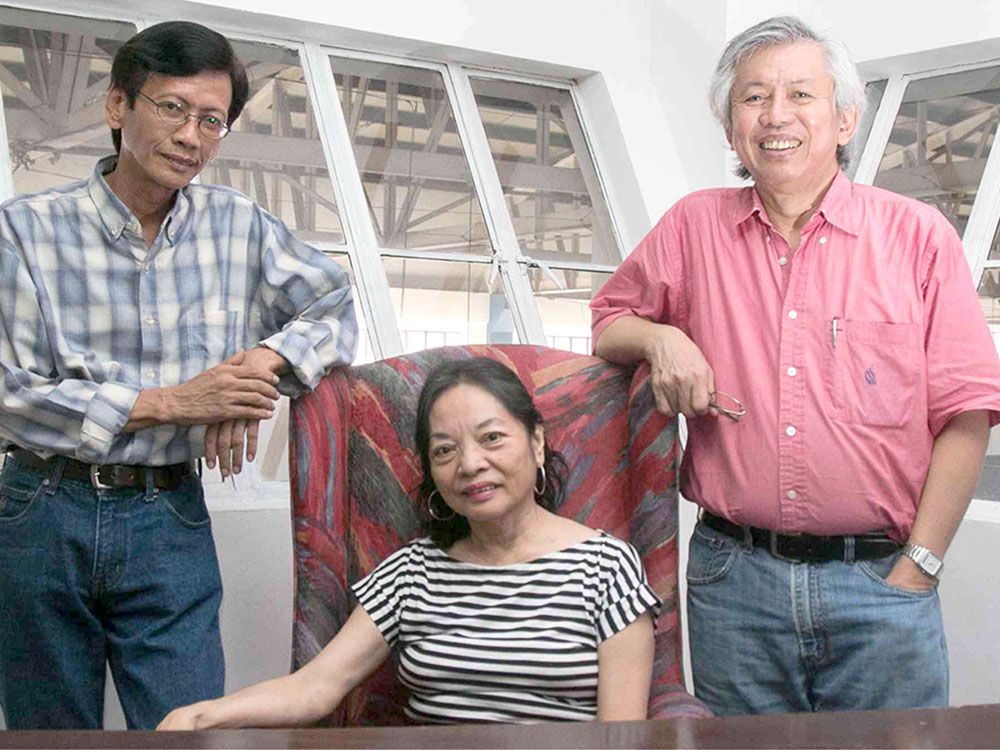

Through a mix of formal training and learning by doing, the Thanabaird clinic was built with a staff of 55, by the year 2000. Of these, only two had been to high school. The program was dealing with 16,000 outpatients and some 700 inpatients a year. With assistance from volunteer pediatric nurse Libby Laing, village health workers also provided ante-natal care, preventative health, nutrition and family planning services.

A satellite health center was established at Kailakuri, some five kilometers away, specializing in services for diabetics and TB. There, Dr. Edric was able to put into practice what he had been working towards for many decades. The diabetes program was managed and run entirely by diabetics. The TB eradication program was managed and run entirely by persons who either were being cured, or had formerly been afflicted by TB.

Dr. Edric’s enthusiasm and energy brought together people of different ethnicities and faith – Bengali Muslim, Mandi Christian, Borman Hindu. They all worked harmoniously together for the good of their community, providing health services for the poor by the poor. He soon realized that he needed to learn Bangla if he really wanted to understand his patients, many of them indigenous people. In a year, he learned to communicate in Bangla and, over the years, became fluent.

In an interview with The Daily Star in September 2011, he said he chose Bangladesh to realize his dream because the people there were “really good” and they did not get health care due to poverty. “I’ve chosen this country in order to give them a little health support,” he said.

The greatest humanist

What Dr. Edric has achieved is truly phenomenal and the essence of his “care for the poor by the poor” has been establishing a methodology attuned to the health needs of an otherwise ignored patient group, a service that can be maintained and implemented at large by this target patient group itself, requiring very little in the way of outside intervention.

This man, who lived a simple but busy life with next to no personal possessions of his own, had a quality most of us are in awe of. The sheer volume of annual health care his operation got through each year – 33,000 outpatients, 1,000 inpatients, and 21,000 receiving health education – for an annual total budget equating to the salaries of just two developed countries’ middle operators, is something so unusual and yet so simple that it bears the quality of real genius.

Expressing an honest, personal, sensitive, caring attitude in every patient-physician encounter, despite objective difficulties such as time constraints, is an essential part of medical care and healing. This, Dr. Edric taught to young boys and girls who served as health assistants and paramedics and used to visit the neighboring villages to give treatment to sick people, especially pregnant mothers and newborns.

He collected money from private donors, including his friends and well-wishers in New Zealand, the U.S. and the U.K., and spent the same for the treatment and welfare of his patients. He lived in a hut, used to wear ordinary lungis which poor people usually do in the villages and used an ordinary bicycle to visit the patients’ houses to render his kind-hearted treatment to them. For more than 35 years, “Doctor Bhai” has been a beacon of shining humanism to the people and the patients there. Throughout his life, he has consistently and boldly stood up for the dignity and respect for all.

Sitting in his mud-built one-room home, he told one correspondent of a reputed daily paper that he was then waiting for a successor. “Many students get MBBS degree in my country and here every year. I’m waiting for one of them to come and take the responsibility to provide treatment to the poor in the area.” But he lamented that no one turned up!