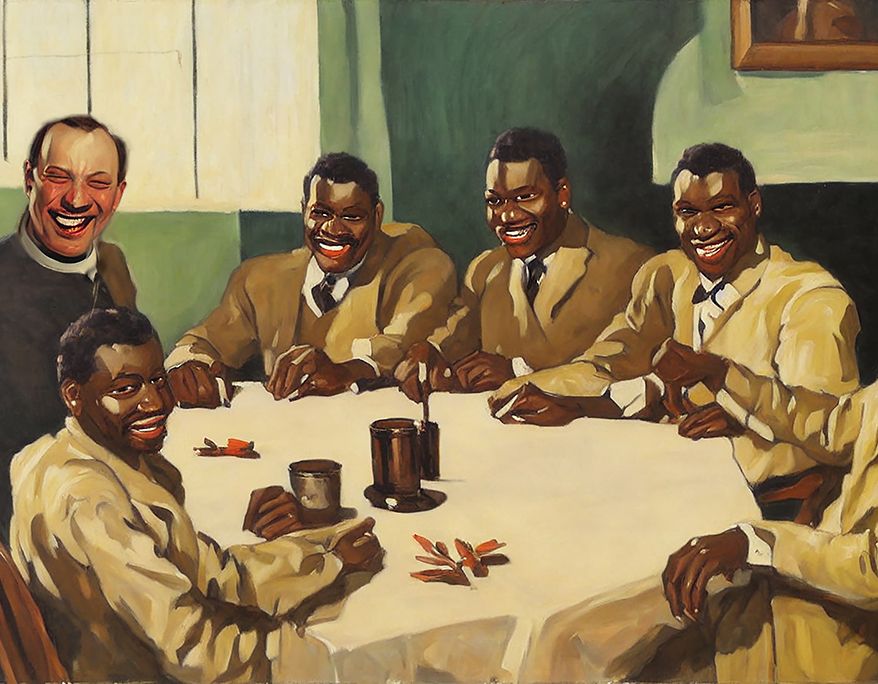

As a society, we hate unfair rules and practices. We cry foul when we sense the referee turning a blind eye to an infraction during a sports competition. We complain to authorities when a favor is given to someone that we know does not deserve special treatment. We get angry when a shabbily clothed woman who wants to deposit her meager savings in a commercial bank is ignored, while a bejeweled matron is given a nice drink as she applies for a loan from the bank.

A more current example is the ongoing protest against the proposed Maharlika fund. GSIS and SSS pensioners feel that the government should protect their hard-earned contributions. Their cry–it’s unfair! It’s foul!

We cry over such brazen acts of unfairness. Yet every day, there are so many demonstrations of partialities right under our noses. Like tiny paper cuts, we feel the pain, but most often, we don’t do anything about it. We seem to be happy people, always smiling and finding ways to lighten up our heavy loads.

Inflation Hurts The Poor

Our balikbayan OFWs with their dollars will boost the local economy. Though they will also be affected by the rising prices of goods, they will still be able to afford the usual “noche buena,” albeit in more modest proportions. This is in contrast to their local counterparts who may not even be able to afford what they used to have before the pandemic. Inflation really hurts the poor more.

Citing government projections, the latest analytical work of the World Bank, “Overcoming Poverty and Inequality in the Philippines,” said that poverty estimates rose from 16.7 percent in 2018 to 18.1 percent in 2021. And even though the economy would grow through 2024, and poverty would gradually decline, the figures would still be higher than pre-pandemic numbers.

The same report said that the COVID-19 pandemic heightened inequality. After declining by 5.4 points from 2000 through 2018, the income Gini coefficient (editor: the Gini coefficient is a measure of statistical dispersion intended to represent the income inequality or the wealth inequality within a nation or a social group) is estimated to worsen in 2020-2024. This means that our country’s wealth or income would be more unevenly distributed among our people. Those who have more will get a bigger share of the pie, while those who have less will have to settle with the crumbs.

With an income Gini coefficient of 42.3 percent in 2018, the Philippines had one of the highest income inequality rates in Southeast Asia. The wealthiest 1 percent of earners capture 17 percent of national income while those at the bottom 50 percent altogether receive only 14 percent.

We should all be crying for fairness, even justice, because the scale of opportunities has tilted in favor of those who already have more in life. We cannot afford to wait too long. And the goal should not just be to go back to pre-pandemic status because that would continue the vicious cycle of poverty and inequality. Why is there no public outcry against this vicious inequality when it begins even before a baby is born and goes on throughout one’s childhood and adult life?

The report cites a reason why we seem to be passive about the unfair distribution of wealth in the country. It recognizes the political or social inequalities that seem to trap the country in this vicious cycle of income inequality. We have a weak system of public accountability so we do not demand better governance that should be demonstrated in public services which truly serve and satisfy the people.

A Long Way To Go

This brief paragraph from the report nails it. We have a long way to go as we have a passive voting public: “Weak local government capacities lead to inefficiencies and thus poor service delivery. Many community services that would enhance equality in opportunities (e.g., health, social protection, nutrition) are provided by local governments, a number of which have minimal accountability mechanisms due to political concentration. At the national level, those who hold the keys to further economic and political reforms in the country … may face deep conflicts of interest as far as pushing reforms that may actually hurt their economic and political dominance in the country.”

The report discusses the past, present, and future prospects for overcoming poverty and inequality. It gives three sets of recommendations, in summary: Heal the pandemic’s scars and build resilience; Set the stage for a vibrant and inclusive recovery; Reduce inequality of opportunity. The details are clearly explained in the report, which is available to the public through the World Bank’s website.

Caring stakeholders in Philippine development, including policymakers and program implementors from national and local levels, should study the recommendations and adopt those within their influence or power. Inquirer.Net