The beginning of the new year for us in South Korea – in 2010, the Year of the Tiger, according to the Chinese lunar calendar fell on February 14 – was celebrated, early in the morning, by every family, with a “ritual for the ancestors.” It is an observance which every first-born son must do – with care, respect and devotion – for deceased parents. Of what does it consist?

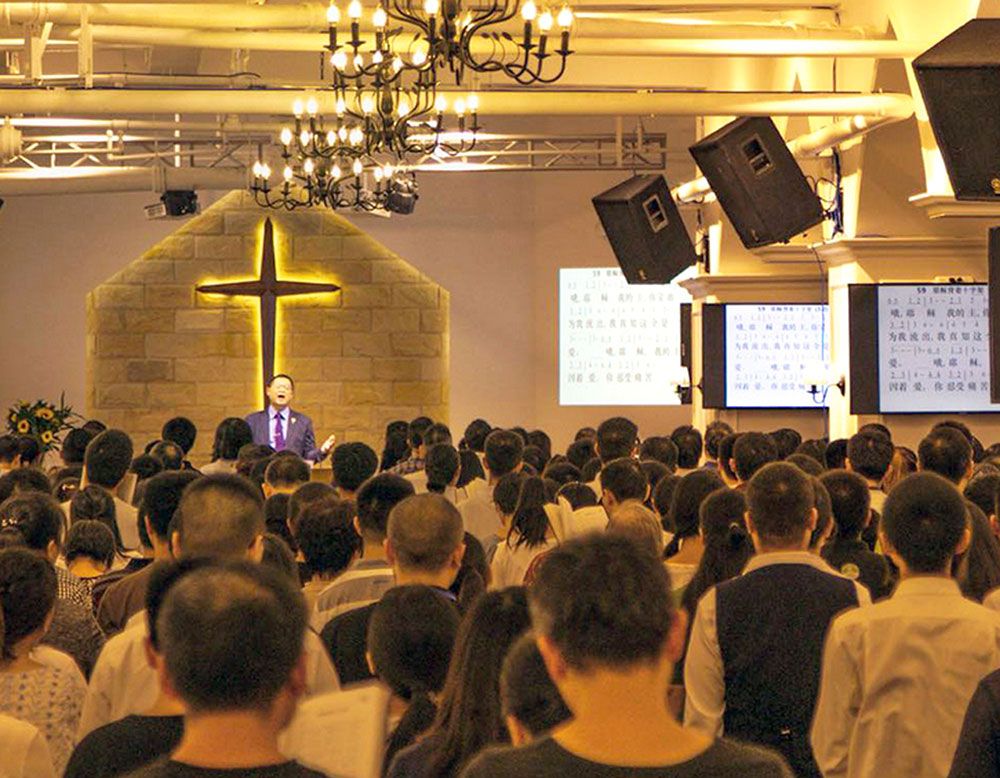

To explain it in a few words is not easy because it is a complex and important reality; to reduce it to a few lines would be to risk not understanding the deeper meaning. Maybe that explains why, in 1500, Fr. Matteo Ricci, the great Jesuit missionary in China, an astrologer, mathematician and a man of great culture, when he spoke of these traditions before the Roman Curia, was misunderstood and from that time on, Catholics were forbidden to celebrate these rituals because they were considered pagan. The question became totally complicated because from that time on, China has always seen the Catholic religion as an enemy of its own traditions and has blocked any rapport with the Church of Rome. Only in recent decades have they understood that the worship of ancestors is not a form of idolatry but rendering homage to family members who have preceded us in heaven and, for that reason, it is permitted that Catholics, too, may celebrate it.

That’s why, on the first day of the Year of the Tiger, I got ready at 7 in the morning to celebrate this important ritual of the Oriental culture, together with the boys of our family home. I had seen it done many times before but never done it myself. But that day, my expert worker took a day off so I had to do it myself. That is not easy, given the complexity of the action which requires much attention to gestures and form. A table with two candlesticks must be prepared, along with a small tablet, on which the names of the deceased persons are written, and a bowl for incense. Then, in a set order, one puts on the table a large quantity of cooked food to offer to the ancestors: steak, chicken, fish, apples, pears, persimmons, candies, chestnuts, wine, rice, took-cook (a special soup that is served only on this occasion), meat patties and pancakes. When everything is ready, one bows before this altar-table with great devotion, then in a kneeling position, twice touching the ground with the forehead; then there is a third bow but less profound. One prays in silence for a few moments, entrusting to these departed souls all of one’s desires and hopes for the new year that is about to begin. Together with the boys, I too bowed, remembering my loved ones in paradise and praying for them.

Then the boys bowed profoundly again before the oldest one there – in this case, me – as a sign of respect. Next, after some words of best wishes and advice for the new year, I gave them a nice “tip”… perhaps the most exciting moment for the boys. Afterwards, with great joy and excitment, everyone ate together the food that had been offered and joyfully we celebrated with traditional games. In this way, celebrating the worship of ancestors with my boys, I spent my Chinese New Year.

Someone could turn up his nose and say: “How could a Catholic priest act like that, without creating scandal and confusion in the faith of these young Christians?” The God in whom I believe and whom the Bible reveals to us is a Great Lord – infinite, omnipotent – who can only smile upon a ritual done out of love for one’s parents who have passed away. Jesus would certainly not be scandalized by these small gestures that are totally human, full of affection and devotion. For whoever might be puzzled at such a statement, I offer an important clarification in a strictly technical sense. Catholicism is not primarily a religion, that is, a group of rituals, prayers, signs, ethical-moral norms, acts of submission to the Divine Being whom one must follow to the letter with fearful devotion. In reality, it is the overwhelming experience of Jesus, risen and alive. It is a life that is lived following Him. It is an encounter with a Person who is alive and present among us.

In fact, the first followers of the Lord were never preoccupied with founding a new religion but only with giving witness to what they had seen and lived: that the Messiah whom they had loved, after His violent death on the cross, was risen and they had seen Him, they had touched Him and they had eaten with Him. They had had such a wonderful experience that they began teaching everyone, fearlessly, the new way (Acts 16:17; 18:26). In the first decades of Christianity, the followers of Jesus were known as those who followed the “new way” and no one ever mentioned a new religion (John 14:6).