One of the booklets I often re-read is titled “Who Moved my Cheese?” by Spencer Johnson. It is a parable about change: reactions, emotions, fears, hope vis-a-vis transformation and evolution in life. It was written in 1998-99, the threshold of the new millennium.

The history of humanity shows a pattern in the transition between one millennium and another. That period is characterized by infinite hopes and untold fears, loaded with apocalyptic nightmares. Johnson personifies in two mice and two humans the beauty of openness to change and transformation and the ugliness of resistance to them; a resistance that plunges the person into pessimism, fear, grumbling and aggressiveness. The two mice and the two humans are accustomed to the “cheese” in the usual corner of a maze, symbolizing the labyrinth of life. At a certain moment, the “cheese” disappears. Instead of seeing it as normal, one mouse tries to find a scapegoat, a mysterious robber, a nameless somebody responsible for the disappearance of the “cheese.” The second mouse has a different response. For him, the disappearing cheese is normal: that is expected when one consumes it without replenishing it. Hence, the mouse takes the inconvenience as a challenge for a fresh start, an invitation to be ready for a new adventure. He takes it as an opportunity to change habits and routines.

For the pessimist, it is a dark and deplorable end, while for the optimist, it is an unexpected and positive opportunity towards a new world.

LIQUID SOCIETY AND FUNDAMENTALISM

The sociologist Zygmunt Bauman has accustomed us to the very meaningful expression ‘liquid society,’ which underlines the consequences of rapid changes. ‘Liquid’ means nothing is stable and, if one doesn’t move, he/she is going to sink and be drawn into. In waters, the faster you move, the more solid you become. ‘Liquid society,’ therefore, underlines mobility – as the waters move, who and what are in them should move as well. Second, moving is a necessity. No other options are available!

TEILHARD DE CHARDIN

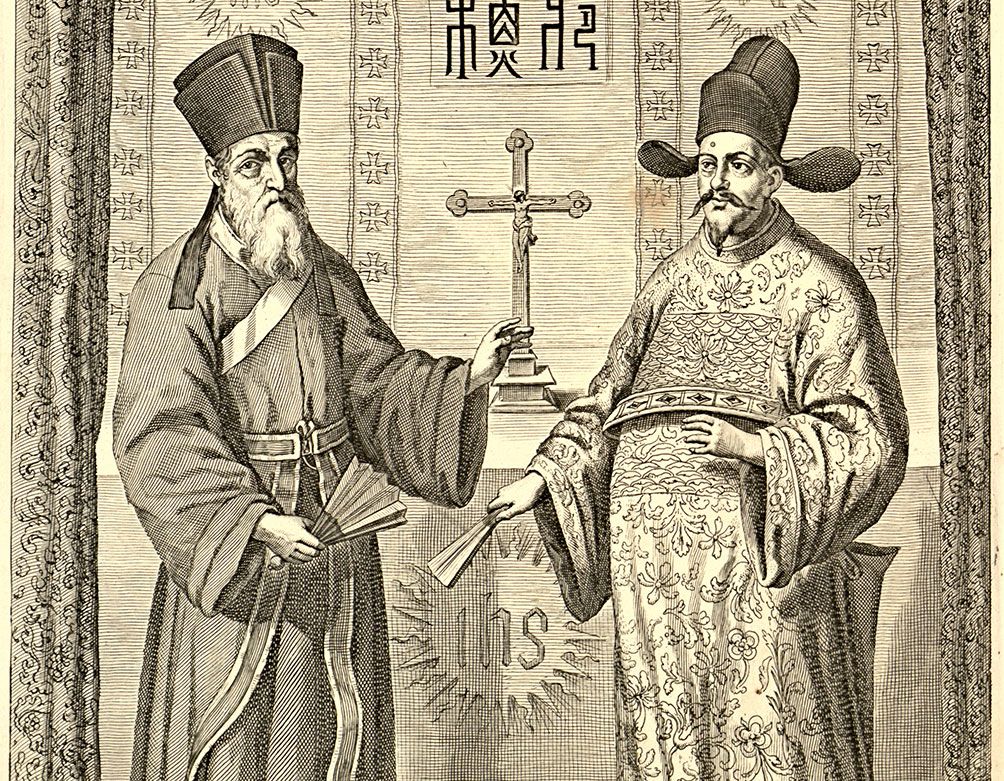

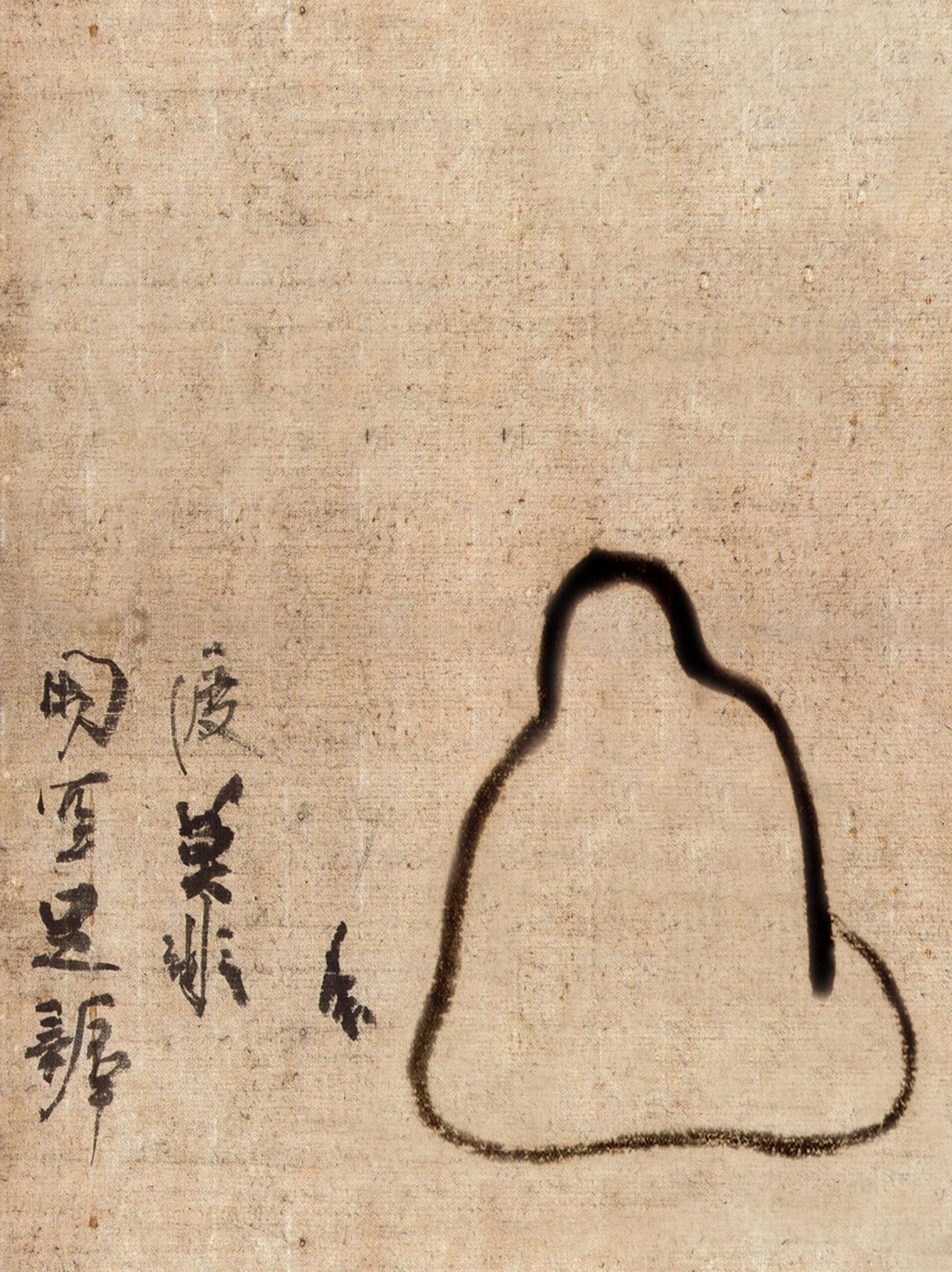

This year, we celebrate the 60th death anniversary of Teilhard de Chardin, a great Jesuit scientist and paleontologist who, through his excavations the world over, ultimately gave an identity to and found evidence about the evolution of humanity. He became familiar with how the different species had adapted to new conditions of life imposed by the transforming environment and climate. He had an evolutionary vision of all Creation.

While all religions, the Catholic Church included, during the first 50 years of 1900, still believed in a God who had created the world in six days as literally interpreted in the first eleven chapters of Genesis, Teilhard offered a new perspective. He gradually elaborated a new synthesis between science and faith. Since science had deeply evolved, he thought that theology had to reshape itself as well. In synergy, faith and science can adequately equip human beings vis-à-vis the challenges of a changing historical and evolutionary season.

He also developed a broader vision of Jesus, the Cosmic Jesus, as nowadays we call it. In line with the Letters to the Ephesians and to the Colossians, where Jesus’ goal and impact go beyond embracing an ever-expanding cosmos, redesigned through the contribution of the scientific theory of the Big Bang, Teilhard saw in the Risen Cosmic Jesus and in God’s love, a mysterious drive behind evolution and transformation. This transformation becomes a visible expression of an inward and hidden energy which prompts the universe towards higher levels of life and communion, which have in the Trinity and in the Risen Cosmic Jesus, its origin and its ultimate goal.

SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL

This year 2015 is also the 50th anniversary of the conclusion of Vatican II, the 21st Ecumenical Council in the history of the Catholic Church. The phenomenon of change and transformation figured prominently in the Council. It would be a pity to celebrate the Golden Jubilee without revisiting, with high interest, the attention Vatican II gave to it – a first in the history of the Church.

Pope St. John XXIII was urged to convoke the Council by attitudes and words such as aggiornamento (updating), “new Pentecost,” and “open the windows of the Church to let in fresh air.” He positively looked at the new world which, since the end of the Second World War, was taking shape. John XXIII was a historian. Therefore, he was equipped to analyze the ups and downs of history. But besides having the know-how, he had a penetrating eye of faith, which helped him to interpret history, by seeing the presence of God in it. It is this faith which helped him to appreciate and support a positive outlook towards modernity. Nothing was more distant from the heart of John XXIII than fundamentalism which is, ultimately, utter rejection of evolution and progress. On October 11, 1962, in his speech on the occasion of the inauguration of the Council, he distanced himself, very clearly and strongly, from the prophets of doom, that is the fundamentalists who, in modern times, see only ugliness and evil.

Attention to history and its dynamics of transformation and evolution became the core of the most famous document of Vatican II, Gaudium et Spes, on the relationship between the Church and the world. The first 11 paragraphs are clearly and positively focused on the changes the world was undergoing. For the first time, an Ecumenical Council used the tools of Social Sciences to scrutinize the time the changes took place, as well as the novelties. Much of the material had been elaborated by almost 100 years of Catholic Social Teaching, which started with the social encyclical Rerum Novarum in 1891, followed by several others. In the previous 20 Ecumenical Councils, the points focus was on heresies against the faith, with no attention given to the historical eras those Councils were in.

In Gaudium et Spes, we find the new methodology of writing documents, that is an inductive one, by starting with a scientific analysis of the conditions of human life and the environment they are framed in. Vatican II, therefore, had several points of discontinuity, a radical novelty, vis-à-vis the traditional Magisterium of the Church. The most revolutionary novelty is the attention it gave to transformation and change, passing from a static and repetitious vision of history to a more dynamic and ever-transforming perception of it. This gave rise to the possibility of human beings intervening as co-creators, with their own increasing responsibility. In this new vision, humans become subjects rather than passive objects of evolution.

One significant quotation is: “The accelerated pace of history is such that one can’t carelessly keep a best of it. The destiny of the human race is viewed as a complete whole, no longer as it were in the particular histories of various peoples. Now, it emerges into a complete whole. And so, human kind substitutes a dynamic and more evolutionary concept of nature for a static one and the result is an immense series of new problems calling for a new endeavor of analyzes and synthesis.” (GS #5)

The Vatican II documents provided clear analyses of the changes in the social, moral, and religious order. The overall mood was positive and hopeful. A quotation that gives a sense of this positivity is: “The People of God believes that it is led by the Spirit of the Lord, Who fills the whole earth. Motivated by this faith, it labors to discern, in the events, the needs and the longings which He shares with other men and women of our time. For faith throws a new light on all things and makes known the full idea which God set for human beings, thus guiding the minds towards solutions that are truly human.”(GS #11)

As a matter of fact, according to the Council, it is the immediate duty of the Church to accompany mankind in the different processes of change which, at times, might be bewildering, amazing, and threatening. And yet, God is not absent from them. “At all times, the Church carries the responsibility of reading the signs of the times and of interpreting them in the light of the Gospel, if the Church is to carry out its thrust.” (GS #4)

PETER DRUCKER

In 1969, four years after Vatican II, Peter Drucker, the founder of the Science of Management, published a book entitled “The Age of Discontinuity: Guidelines to our Changing Society,” a rather prophetic analysis and reflection. He identifies four new traits which were not present before: (1) the explosion of new technologies that would result in major new industries; (2) a change from an ‘international economy’ to a ‘world economy,’ an economy still, in those days, without policy, theory and institutions; (3) a new socio-political reality of pluralistic institutions which would pose political, philosophical, and spiritual challenges; and (4) the new universe of knowledge based on mass education and its implications in world life, leisure, and leadership.

These prophetic insights can be integrated with the ones of de Chardin and Vatican II. They provided a powerful viaticum as we crossed the threshold of the Third Millennium. We are still there, even if we are already 15 years into the Third. They provide a positive vision for welcoming the challenging future.

The wisdom of faith

Right now, all types of sciences provide us with immense resources to detect the changes, to describe them and to accompany them. But it does not provide us with the wisdom we need to understand those processes and their implications to our own person. Technology has boosted transformation and changes tremendously but, often, at the expense of human beings and the environment.

The world, besides science, needs a deep vision and motivation which are provided to us by the Paschal Mystery of Jesus. Teilhard de Chardin, the Vatican II and scientists, such as Peter Drucker, provide us with tools, both for scientific understanding and the wisdom we need, to configure ourselves with this transformation and to be active in these processes, so that we might detect what is positive and negative. In the light of science and the Resurrection, in the light of the experience of Jesus, we can, in a sense, master those immense processes. Let us then be confident, let us …from our own hearts and minds…eradicate the cancer of fundamentalism. And may the divine attitude of hope, so present in the Heart of Jesus, provide us with the energies necessary to face the mystery of change. May our faith provide us with the strong belief that, at the end of the journey, as Teilhard says, the full light of the Sun, who is Christ, will burst unto us.