María’s nightmare started with gang members demanding that her husband pay a “war tax”–a euphemism for extortion–on a cargo truck he owned. He always paid the 6,000 lempiras ($250), but gangsters killed him anyway, bursting into their San Pedro Sula home four years ago and dragging him away. He was found dead shortly after, with signs of torture and six gunshot wounds to the head.

María, 29, fled with her three children, all under the age of 10, to another part of Honduras. Then, just months later, her brother–who had been deported from the United States 18 months earlier–was also killed by gang members. Figuring she was next, María fled the country with another brother.

“We left the next day with 2,000 lempiras [$84] … practically nothing,” she said during an interview at the offices of the International Committee of the Red Cross in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras.

She left her children with their grandmother, fearing they would suffer too much on the journey, and headed to the US. María made it as far as Tabasco state in southern Mexico. There, she was detained and deported by Mexican migration officials, though her brother “ran faster than me,” she said, escaped and made it to the US.

María, a pseudonym to protect her identity, is among the thousands of Central Americans attempting to escape violence and poverty but are ultimately deported back to the country and conditions they fled from. The northern triangle countries of Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras rank among the deadliest in the world, with the homicide rate at times topping 80 people per 100,000.

Reasons For Migration

Even with tougher US immigration policies and a route through Mexico full of risks such as kidnapping, robbery and rape, incentives to leave are strong, observers in Central America say. They cite three main reasons for the outward migration: violence, poverty and plans for family reunification, though each of the three countries has different dynamics.

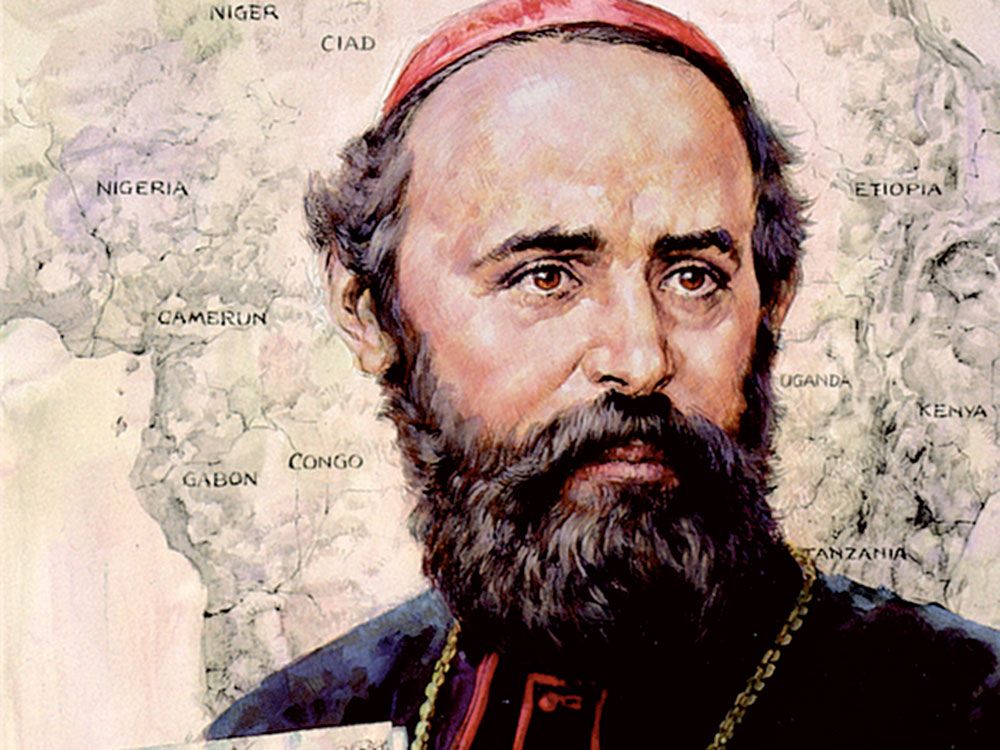

The violence forces many to flee, said Scalabrinian Sr. Lidia Mara Silva da Souza, director of the Honduran bishops’ Human Mobility Ministry, which attends to migrants transiting the country and those returning, involuntarily or otherwise.

“The biggest problem is extortion. We all pay it,” she said. Such is the practice in the neighborhood where the Scalabrinian sisters live, Silva said. “In the payments we make to private security companies, extortion is included, and they have to pay the gangs, so we all pay.”

Women have fled Honduras in larger numbers in recent years, Silva said, often to protect their children, who are preyed upon by gangs or forcibly recruited as teenagers. Boys become foot soldiers while girls are required to become gangsters’ girlfriends against their will.

“It’s to save their children from gangs,” she said. “The issue is violence because these women not only work to feed their families, but they also have to pay extortion–and their children are at risk.”

Family Separation

Those seeking refuge face numerous obstacles. Families are being turned away before they can reach the border to ask for asylum. Those who manage to cross the US border found their children at risk when a “zero tolerance” policy, announced by the Trump administration in April last year, separated more than 2,300 children from parents.

The policy provoked outrage and has since been rescinded; a federal judge ordered that children be reunited with parents. Now under tougher US policies, domestic and gang violence will no longer typically qualify for asylum claims.

Into this climate of violence, deportees are arriving back in Honduras in massive numbers. The Observatorio Consular y Migratorio de Honduras has counted 39,585 returned migrants arriving between Jan. 1 and July 15, 2018 (almost all from the United States and Mexico)–44.7 percent more than during the same period in 2017, according to Honduran newspaper El Heraldo.

The three Scalabrinian sisters from Brazil run two Returned Migrant Attention Centers at the airports in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula. The centers receive planeloads of migrants several times a week and help returnees with having IDs reissued, finding transportation or offering medical and psychological help.

Mostly, though, the sisters try to offer a warm welcome, serving the migrants coffee and baleadas– Honduran specialties of flour tortillas and red beans–and a dose of dignity for people arriving with their dreams dashed and “devastated,” Silva said.

“Something I believe is pastorally fundamental when we speak of migrants and refugees and displaced persons is looking them in the eyes so they feel that they are important, that they have dignity, that they feel they matter,” Silva said.

Those who have been deported often can’t return to their former neighborhoods because the threats they fled from remain. Moving to a new area is risky because the gangs look suspiciously at newcomers; those previously living in zones dominated by rivals are assumed to be enemies.

Return

Since returning to Honduras, María occasionally works processing coffee. She tried to start a small retail business with seed money from a nongovernmental group, but a new set of extortionists forced her to abandon those plans before she even opened.

María still receives telephone threats, she said, connected with her late husband’s business. “The gangs always have someone deep inside the police,” she said. That’s why her family never reported her husband’s killing, even though he was a physician. It’s also why many Hondurans distrust the authorities.

“These criminal groups can find anyone,” said Jaime Flores, coordinator with the Observatory for the Rights of Children and Youth of Honduras with Casa Alianza (Covenant House in Latin America.) “They have a network that can find you wherever you are.”

Ingrid Álvarado worries about that. She fled northern Honduras in February after the Mara Salvatrucha MS-13–which disputes the control of neighborhoods with the rival Calle 18 gang–demanded that her 14-year-old nephew join its ranks. “They said that if my nephew [who lived in her home] didn’t join, I would pay with my life and my children’s lives, too.”

She and her nephew made it through Mexico, where she says she escaped being raped twice, by riding small buses to the US border at El Paso, Texas, where they requested asylum.

Álvarado, 26, says her nephew’s asylum claim is still being processed. She abandoned her claim after three months in detention, saying, “I couldn’t take it any longer,” along with worries about her two children, ages four and seven, whom she left with her grandparents.

She returned to Honduras in May to a new neighborhood, controlled by Calle 18. The mere fact she had lived in an area dominated by MS-13 makes her suspicious to them, she said.

Warnings by US officials, most recently by Vice President Mike Pence, attempt to dissuade migration. Honduras’ First Lady Ana García recently tweeted photos of her talking to separated families in Texas, along with the admonishment, “Don’t take the risk of the migrant route.”

Honduran officials encourage investing the money in starting a small business, even though extortion is commonplace and police protection nonexistent.

Central Americans know the risks. The Scalabrinian sisters minister to families of migrants killed in Mexico by drug cartels and those who lose limbs falling under the Bestia freight trains as they steal rides atop in Mexico.“ What happens on the way to the US border would be less grave than what they live here,” Flores said of the migrants’ thinking.

Most Unequal Country

A wave of political unrest and repression followed a coup in 2009 that ousted then President Manuel Zelaya. President Juan Orlando Hernández won the election in 2013 amid allegations that money embezzled from the state social security system funded his campaign. Another spate of violence erupted after his disputed re-election late last year. The unrest prompted an estimated 30 percent increase in outward migration in early 2018, Silva said.

Social and economic factors also push people to leave. Mining concessions and other megaprojects are displacing populations in parts of Honduras. Inequality has increased: Honduras ranks as the most unequal country in Latin America and sixth most unequal country in the world, according to the World Bank.

Elites in Honduras enjoy tax breaks, such as profits on fast-food restaurants, at the expense of people in lower economic classes, said Ismael Zepeda, an economist with Foro Social de Deuda Externa y Desarrollo de Honduras (FOSDEH), a nonprofit public policy organization. Electric bills have increased, while the sales tax rose to 15 percent from 12 percent.

Remittances from migrants provide much of the “macroeconomic stability” in the country, and many Hondurans work in the informal economy, where “studies show most people earn less than the minimum wage,” Zepeda said.

“The poor are the ones that fund the poor,” he said. “The extra 3 percentage points [of sales tax] fund the main anti-poverty program.”No northern triangle country does especially well in attending to people who live in poverty or returned migrants, said Elizabeth Kennedy, a social science researcher in Tegucigalpa. But in Honduras, “this is close to a corporate state. They don’t provide services for their citizens and they even talk about farming out the services — and do so with great pride.”

Kennedy’s previous research of children fleeing neighboring El Salvador published in 2014 showed violence was a factor in the majority of migration cases. “Violence in these three [Central American] countries is targeted. It’s not generalized,” she said. “70 to 80 percent of homicides are someone being shot on their way to work, in their car, in their home, sleeping in their very bed … it’s clear then that person was targeted.”

Gangs control entire neighborhoods and enforce their own rules on the population, she said. “Gangs prefer that one person from each of the [neighborhood] households is in some way associated with them … that lessens the likelihood they will be reported,” Kennedy said. “The gang believes that it is benevolently providing protection for its family, so of course you would pay them a small amount in return [extortion] for that.”

Additionally, “what’s in the neighborhood belongs to the gang,” she said. “They feel that the girls and women in their neighborhood are their property and they have a right to use them. ‘You belong to us. You live here. You’re supposed to be part of us’ … that’s why [boys] can be forcibly recruited.”

Sugar Cane And Coffee

Outward migration is felt in rural areas, too. In the hills of Honduras’ western Copán department, many in the local population grow sugar cane and coffee on small plots but find prices unattractive and the costs constantly climbing. In the hamlet of Zapote, 20 people have left in 2018 from a population of just 200 families, local coffee farmers said.

“If the price of coffee goes up, these people in the United States will return,” said Moises García, a coffee farmer who previously picked carrots in Canada under a temporary work program and was able to expand his landholdings in Honduras with the earnings.

Drug cartel activities are common in the region, which lies on the transit route from South America to Mexico. While those leaving insist they’re doing so for economic reasons (many are loath to cite drug cartels as the reason), locals speak quietly of people fleeing because of threats.

Fr. Germán Navarro, a parish priest in Copán, said the number of intentions at Mass for people en route to the US has increased. Some stop by to ask for a blessing, but many just leave, sending him messages from Mexico, asking for prayers as they encounter tough situations.

Roberto, 24, was among those heading north. He lost much of his land after a relative died and left debts for which his family was the guarantor. He could earn the money in the United States needed to get the land back. Earlier this year, he paid a “coyote” $7,000 to take him to Houston; a cousin and six friends also paid the same smuggler.

They rode the length of Mexico in a trailer, and upon reaching the US-Mexico border, waited in a safe house for two weeks. Roberto, who kept his name private for safety, suspects the human smugglers were part of a drug cartel. They were waiting for an illegal shipment, he said, and “used us as a decoy” as they moved the drugs across the Rio Grande River into the United States.

Roberto was caught and deported back to Honduras, facing even deeper debts from his attempt to leave. But one person in his group made it, which Roberto attributed to “luck.” Now with no way to escape given his small land holdings and the poor prices for sugar cane, he ponders his fate.

“I was destroyed,” he said of his return. “Knowing how things went, knowing all the money that I owe, you think ‘how?’” he said, his voice trailing off.

As for María, her children are, for now, keeping her in Honduras, she said. But she confesses a temptation to leave again –“when I get desperate.” Published in the “Seeking Refuge” feature series in Global Sisters Report, a project of Catholic National Reporter.