In the period following World War II, an uprising of the farmers, led by the Communist Party, took place in the Philippines. The most important cause behind the communist-led peasant movement was the pattern of landownership where agricultural lands were concentrated in the hands of a relatively small number of big landlords and the majority of the peasants were their tenants. Emerging during the Spanish colonial period, this landownership pattern continued to intensify throughout the American (1898–1935), and the Commonwealth (1935–1946) periods.

Most tenant farmers were sharecroppers, and the predominant sharecropping arrangement was fifty-fifty. Unlike lease holders who paid a fixed rent, the sharecroppers had to hand over half of their harvest. This type of sharecropping was helpful when the harvest was poor but was a disincentive to efforts to increase production.

Nonetheless, even under these conditions, the traditional landlord-tenant relationship, characterized by paternalistic patron-client ties, maintained the social order in farming villages, and large-scale peasant unrest did not spread. During the American colonial period, however, this traditional landlord-tenant relationship was gradually undermined, mainly in the rice-producing plain of Central Luzon, due to the commercialization and mechanization of agriculture, the growing absenteeism of the landlords, and a rise in population. It is around this time that disputes between landlords and peasants in Central Luzon intensified.

The communist-led peasant movement organized the People’s Army of Liberation in 1942 (known as Huks—Filipino acronym) and staged an armed rebellion. The Huks not only fought bravely against Japanese troops but also virtually carried out their land reforms in Central Luzon after the landlords took refuge in the cities during the war. After Japan’s defeat, the Philippine government dominated by the landed elites, came back to restore the old order. The Huks stood by the peasants and opposed this move, escalating their confrontation with the government and landlords.

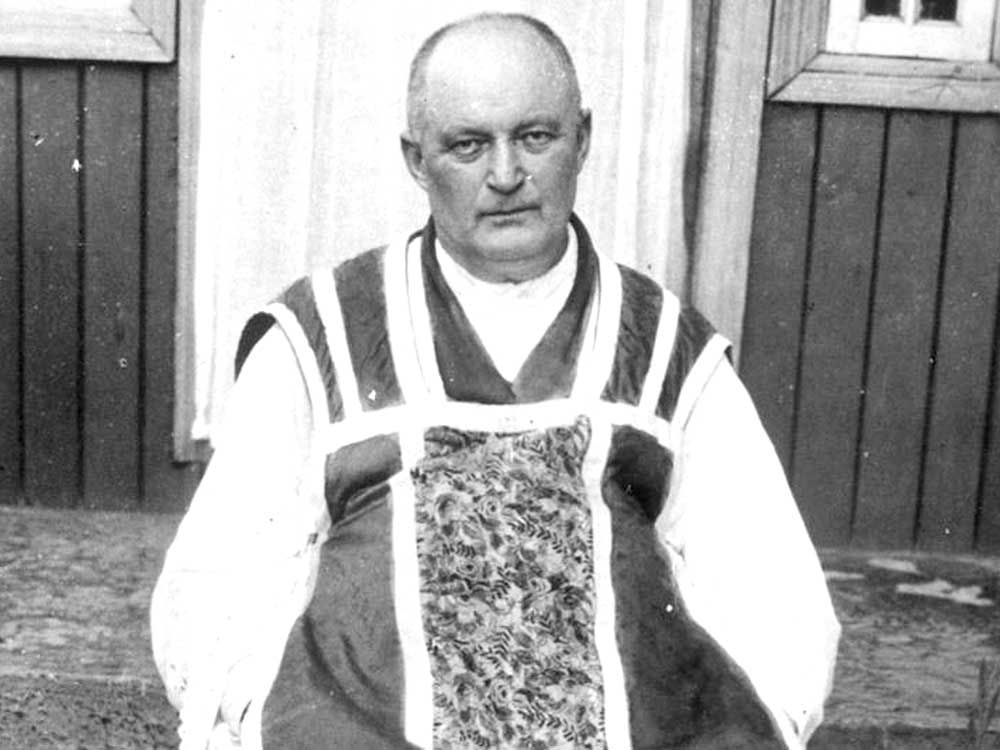

The government outlawed the Huks and, with military and economic assistance from the United States, successfully put down the Huk rebellion by means of large-scale military operations combined with a policy of attraction. In 1952, Luis Taruc, the supreme commander of the rebellion, surrendered and this practically ended the civil war. It was under these circumstances that the Federation of Free Farmers was formed. It was Dean Jerry’s brainchild which was officially inaugurated in San Fernando, Pampanga, on the Feast of Christ the King, in 1953.

Contact with the farmers

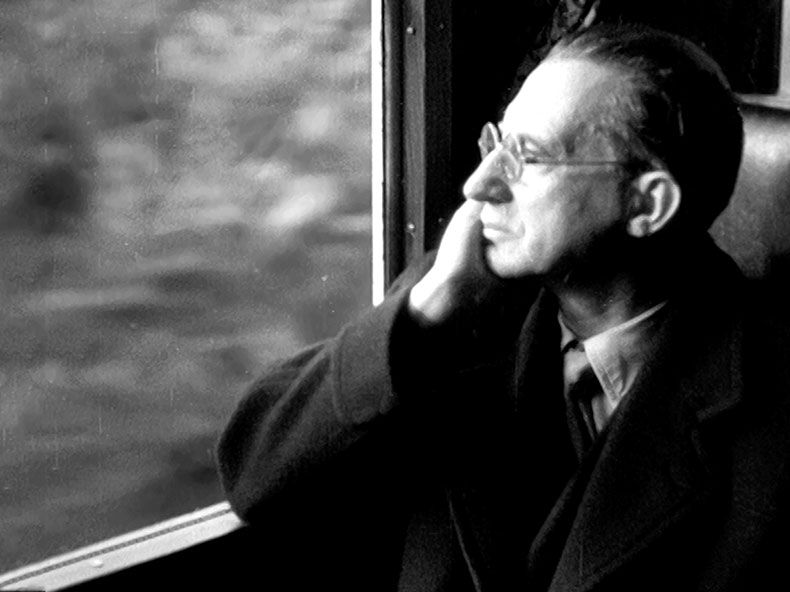

Jeremias U. Montemayor was born in 1923 into a wealthy landowning family in Alaminos, Pangasinan. When he was 13 years old, his mother enrolled him at the Minor Seminary run by the Society of the Divine Word (SDV). Two years later, he transferred to the Jesuit-run San Jose Seminary in Caloocan.

After three years of training at these two seminaries, however, he left the seminary and entered a high school. Jeremias, subsequently, enrolled in the College of Liberal Arts, Ateneo de Manila. Dean Jerry later wrote that he considered the training he had received in the two seminaries as the best, most basic and most solid part and foundation of his entire education.

Then the Second World War came and with it the Japanese invasion (1941). His family evacuated to a nearby barrio which the Japanese did not reach. They had the basic necessities and were surrounded by tenants who obeyed and respected them. It was during this period that young Jeremias got a clear picture of the lowly, simple and unexciting life of the farmers.

After the war, he went back to school and finished Bachelor of Arts at the Ateneo de Manila. Then he applied for a teaching job at the same school. While teaching, he enrolled at the Ateneo Law School and graduated magna cum laude.

On New Years’ Day, 1949, he married Nieves “Bing” Quimson, the finest pianist in town and the regular organist in the church. Then the children came, one by one. The desire to help the small farmers took some of his time away from his family but his wife was very supportive of his project. Shortly afterwards, he gave up his post as dean of the Ateneo Law School in favor of his work for the farmers.

The FFF

The Federation of Free Farmers (FFF) developed quickly but it did not gain acceptance in some sectors of society. Since it was working for the grassroots, a few church leaders suspected it to be subversive. Nevertheless, Dean Montemayor had friends and patrons who, like himself, gave their time and energy for the good cause. Even the late President Ramon Magsaysay lauded the FFF.

Dean Jerry argued that the root of the country’s social, economic and political problems lay in the poverty of the peasants which, in turn, was a result of the fact that they had been merely tenants and had to look up to a landlord as their master. The peasants were at a disadvantage in almost everything except numbers. And herein lay their hope.

If they were properly organized, nothing could withstand their strength to improve their lot or to protect their rights. Then, Montemayor enumerated what a peasants organization could do: it could be a weapon of common defense and serve as a bridge between government and people, as an instrument for agrarian peace, as a means for economic advancement of the peasants; and as a voice to protect their interests in government action.

Dean Jerry envisioned the family-size farm as the paramount objective of the FFF. By giving every peasant a family-size farm of the area that would provide him and his family a decent livelihood, the problems of the peasantry would be solved from the roots. To him, the nationalization of farm land, as was the case in the communist countries, meant simply that all farmers became tenants tied to a single giant landlord, the state.

He thought that this objective could be achieved in either or both of two ways: by the settlement of public agricultural lands; by the expropriation and subdivision of landed estates. Despite all the obstacles, Dean Jerry believed that peasants, once united and organized, could wield overwhelming political power to plan and apply such reforms to promote the well-being and the interests of the majority. He called this a democratic, peaceful revolution.

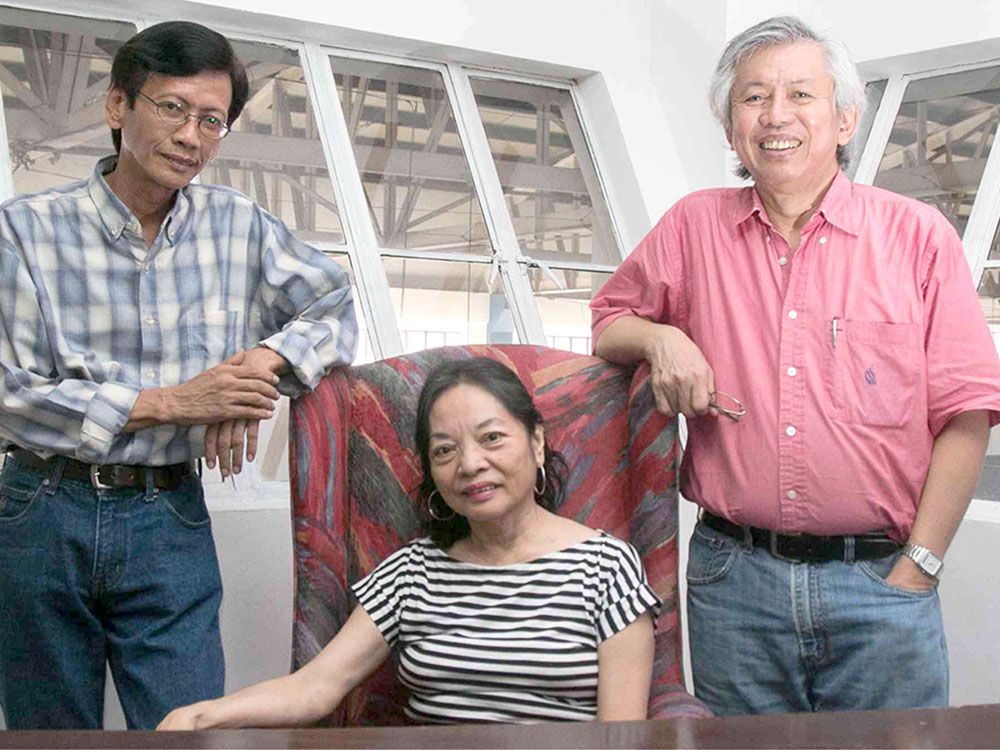

Together with other peasant organizations, the FFF has been instrumental in the enactment of practically all the relevant laws and regulations on agrarian reform since the time of President Magsaysay. The very existence of the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) and the Landbank of the Philippines (LBP) was a direct result of their efforts. The FFF was also a pioneer in cooperatives.

The FFF is currently one of the largest and most effective non-governmental organizations of rural workers in the Philippines with branches and footholds in some 50 provinces. Memberships, consisting of agricultural tenants, owner-cultivators, agricultural laborers, fishermen and settlers, total around 200,000. But the Agrarian Reform with the expropriation and division of the landed estates, as was Dean Jerry’s dream, remains still largely unfulfilled as the following story, unfortunately, exemplifies.

Hacienda Luisita

Hacienda Luisita (HL) is 6,453 hectares of agricultural land in the province of Tarlac, Philippines, an estate as large as the land area of the cities of Makati and Manila combined. It was once part of the holdings of Compañía General de Tabacos de Filipinas, better known as Tabacalera, which was founded in 1881 by a Spaniard, Antonio López y López.

The HL was acquired after the war by the Cojuangco-Aquino family with the condition that it had to be partitioned among the tenants after ten years. To date, despite various promises including a Supreme Court decision in April 2012, overlooking the spirit of the Land Reform, the Cojuangco-Aquino have continued to deny the farmers’ rights by deception and violence, like the Mendiola massacre in 1987 and the Hacienda Luisita massacre in 2004.

The Mendiola massacre was an incident that took place in Mendiola Street, San Miguel, Manila on January 22, 1987, in which state security forces violently dispersed a farmers’ march to Malacañang Palace. Thirteen of the farmers were killed and many wounded when government anti-riot forces opened fire on them. The farmers were demanding fulfillment of the promises regarding land reform made during the presidential campaign of Cory Aquino.

On November 16, 2004, twelve picketing farmers and two children were killed and hundreds were injured at Hacienda Luisita itself when police and soldiers stormed a blockade by plantation workers. The protesters were pushing for fairer wages, increased benefits and, more broadly, a greater commitment for national land reform.

It is the story of one powerful family that has produced two presidents of the country, Cory and Benigno III, blind to its obligation to poor citizens and the decades-long struggle of ten thousand of farm workers and their families for land and justice. The Cojuangcos have often garnered criticism for their unyielding ownership of the estate. The Filipino people see it as a symbol of the country’s paralyzing oligarchy, with some of the country’s most powerful figures all having stakes in the property.

Up to the last day

Dean Jerry was aware of this difficulty and decided to give the example. Belonging to a clan of landowners, he suggested to his mother to award to the tenants their share of land according to the laws of Land Reform but his mother and siblings kept quiet about it. Yet he was decided to follow his inspiration. In an unprecedented gesture, he waived his rights to whatever land would be his inheritance. He became landless but God gave him what his family needed for the education of his children. Years later, he said: “I began to realize that I had started then not only to learn but to teach by word and example, the Word of God, as I understood it.” But even now, none of his relatives ever understood what he did.

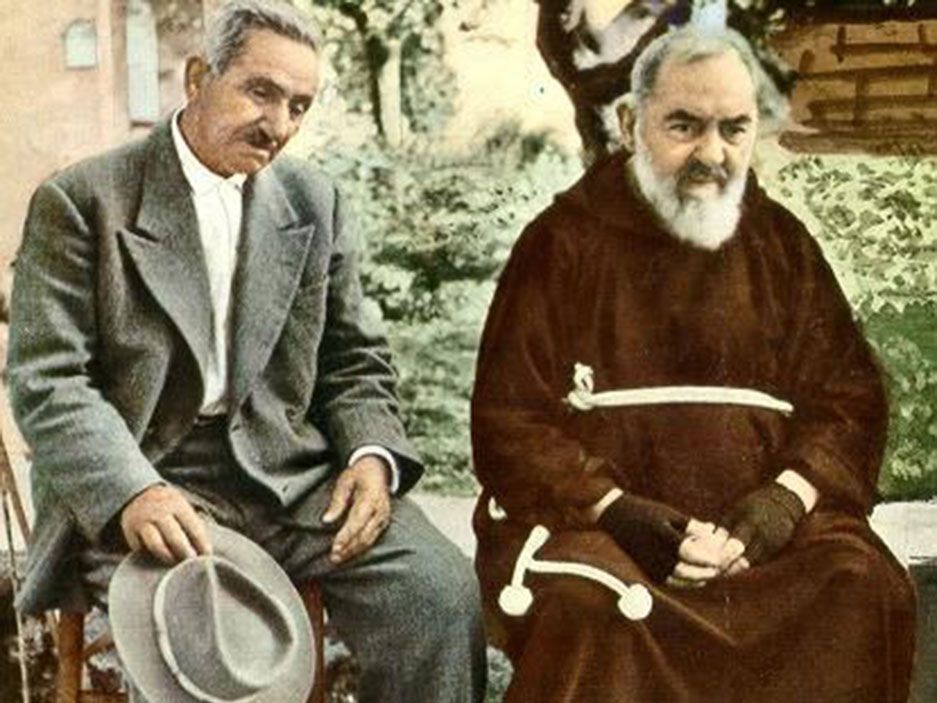

For half a century, Dean Jerry incessantly proclaimed the basic dignity of the small Filipino farmer and the peasant’s importance as backbone of the nation. His books, particularly, “Ours to Share” and “Philippine Socio-Economic Problems” became the “bible” of many social activists. The significance of his efforts to promote Catholic social teachings was recognized by the Vatican which named him to the Council of the Laity in 1968. It was there that he also became friend with Cardinal Karol Wojtyla who later became Pope John Paul II.

Yet, despite his great stature and intellect, Dean Jerry, in times of adversity, always tried to draw out the hidden strength of the farmers by depending on them. When big decisions needed to be made, he summoned all his powers of observation and intuition to determine their real aspirations and inclinations. In times of victory, he was quick to point out the strength, the generosity, and the virtues of the farmers and attracted everyone by focusing attention away from himself.

Stories of the multitudes of farmers he met are filled with anecdotes of how he slept on the bare wooden floors of their nipa huts or under the trees, how he ate what they ate, how he sometimes rode tricycles to their meetings, and how he never turned away anyone who wanted to talk to him in the barrios.

Despite being born to a landlord family, Dean Jerry was, at heart, a small farmer. And he was happiest when he was among them. It was, therefore, truly symbolic that he died peacefully of heart failure as he took a nap in a farmer’s nipa hut while resting after yet another one of his never-ending farmer-seminars, and only few kilometers away from where he had founded the FFF 50 years earlier. He was 79 years of age.