“Even Jesus of Nazareth could not offer any earthly solutions to the problem, except the promise of a celestial one. He said: ‘Blessed be the poor for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.’ Must the poor suffer death in order to come into salvation?” (From “A Fetish for the Poor” by Samito Jalbuen)

A few years back, 12-year-old Mariannet Amper from Davao City captured the attention of the country when she hanged herself with a nylon rope. She left a letter under her pillow describing her failed hopes and aspirations: “I wish for new shoes, a bag and jobs for my mother and my father. My dad does not have a job and my mom just gets laundry jobs.” She added: “I would like to finish my schooling and I would very much like to buy a new bike.”

“It is time we recognized poverty for what it is: a brutal denial of human rights,” declared James Gustave Speth in 1998, when he was still the administrator of the United Nations Development Program. “The poor are deprived of many things, including a long life.” With the absence of basic amenities such as safe drinking water and health care, most people living in developing countries – including the Philippines – have a life expectancy of just 40 years.

Most poor people are illiterate. In the Philippines, only 5% of the population is not able to read, write, and perform arithmetic. But the sad thing is: school dropouts are rising, according to the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD).

Research findings collected by the online news organization Rappler, and posted on its website last March, showed the Philippines as the 5th country in the world with the most number of school dropouts. A study done by the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) showed that, for every 100 children who enter Grade 1, only 71 complete elementary education and only 69 will enroll in high school. Of the remaining 69, only 51 are expected to graduate.

If this trend continues, there might be more illiterate Filipinos in the future. “Illiteracy imposes severe limits on the access of poor people to knowledge, informed opinions and political participation,” Speth pointed out.

A new study showed that poverty – along with neglect in childhood – may have a direct effect on a child’s brain development. The study, which was published in Jama Pediatrics, found children, living in poverty without adequate nurturing, had a smaller hippocampus, a brain region linked to learning and memory, than those who weren’t poor or neglected.

Nicole Ostrow, in an article dispatched by Bloomberg News, wrote: “Poor children, even if not neglected by parents, were found to have less gray matter, which is linked to intelligence; less white matter, which helps transmit signals; and smaller amygdala, an area key to emotional health.”

More often than not, children suffer the most when it comes to poverty. Denis Murphy, in an article which appeared in World Mission, shared this reality: “In Tondo (Manila), young girls of 12 and 13 years of age act as prostitutes for truck drivers, security guards, and other men who hang around the piers at night. The girls charge P30 for feeling of the breast and bodies and P300 for sex, often in the back of garbage trucks.”

NOT A POOR COUNTRY

The Philippines – with 7,107 islands and a land area of 30 million hectares – is rich in natural resources…but poverty is rampant. “The Philippines is not a poor country,” declares Niklas Reese, a German who is one of the editors of the 500-page Handbook Philippines. He knows much about the country as he has been living in the Philippines for several years now. In fact, he is an alumnus of the Our Lady of Fatima Academy in Davao City.

Reese cites these reasons: “The numbers of shopping malls, sports utility vehicles, and private subdivisions increase year by year. Many residential enclaves are more luxurious than those found in Central Europe. Natural resources are abundant; its people are educated and skilled.”

But the German lecturer is very much aware that one in four Filipinos live on less than a dollar a day. “The Philippines is not a poor country,” he points out, “but it is a country with many poor people.”

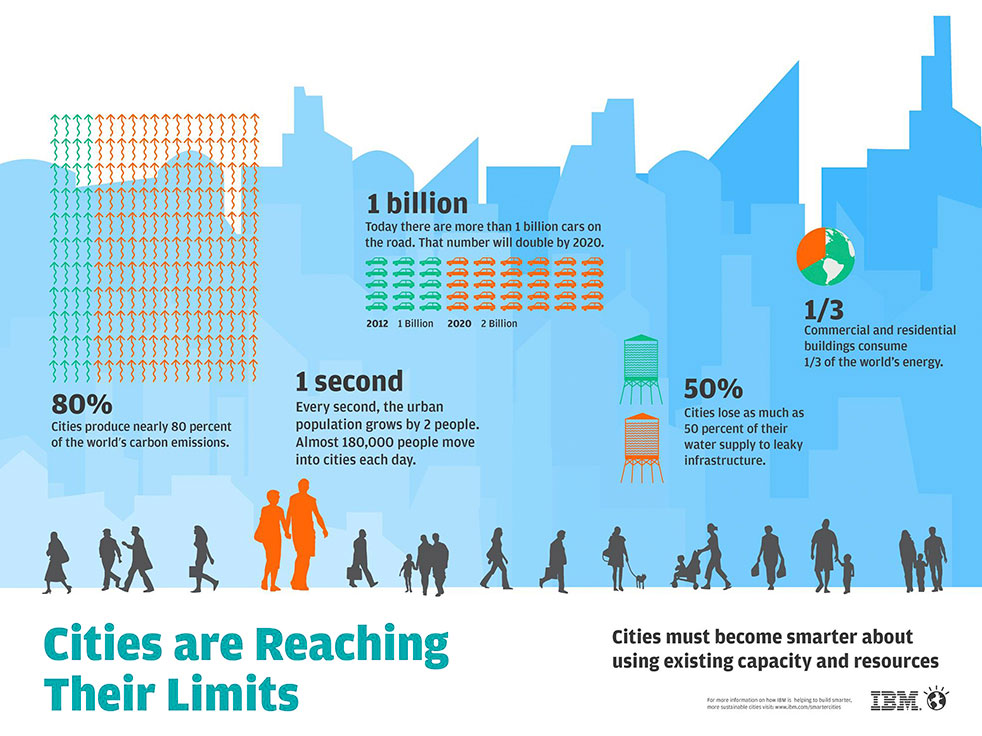

POVERTY BY NUMBERS

Last July, the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) released its latest report on the country’s official poverty statistics for the basic sectors for 2012. The PSA report provided the estimates of poverty incidence for 9 of the 14 basic sectors identified in Republic Act 8425, Social Reform and Poverty Alleviation Act, using the income and sectoral data from the merged Family Income and Expenditure Survey (FIES) and Labor Force Survey (LFS).

In 2012, fishermen, farmers and children consistently posted the highest poverty incidences among the nine basic sectors in the Philippines at 39.2%, 38.3%, and 35.2%, respectively. The other sectors had the following poverty incidences: self-employed and unpaid family workers, 29%; women, 25%; youth, 22.3%; migrant and formal sector, 16.6%; senior citizens, 16.2%; and individuals residing in urban areas, 13%.

The PSA reported that, in the first six months of 2013, the poverty incidence was estimated at 24.9%, slightly better than the 27.9% in 2012.

A MATTER OF DEFINITION

Poverty, however, is a matter of definition. The poor, according to the United Nations, are those living below what is considered the minimum level consistent with human dignity. Social well-being covers the basic necessities of food, clothing, shelter, education, and health, among others.

In his book, Poverty as Relative Deprivation: Resources and Style of Living, Peter Towsend defined poverty in terms of relative deprivation. Individuals, families, and groups in the population can be said to be in poverty when they lack the resources to obtain the type of diets, participate in activities and have living conditions or “style of life” which are customary or at least widely encouraged or approved in the society in which they belong.

In some instances, the food threshold is used by experts to help measure food poverty or “subsistence,” which may also be described as extreme poverty. The food threshold is the minimum income required by an individual to meet his/her basic food needs and satisfy the nutritional requirements set by the Food and Nutrition Research Institute, while remaining economically and socially productive.

According to the PSA, a Filipino family with five members needs at least PhP5.590 (about USD 130), on the average, every month to meet the family’s basic food needs, and at least PhP8,022 (USD 185), on the average, every month to meet both basic food and non-food needs.

“To a man with an empty stomach, food is god,” India’s Mahatma Gandhi once said. To which Pulitzer-prize winning American author Pearl S. Buck added: “Hunger makes a thief of any man.” Hunger persists across the country and while the situation has improved, it remains “serious,” according to the International Food Policy Research Institute. Its Global Hunger Index (GHI) score of 13.2 ranks 28th worldwide in 2013; it was 19.9 in 1990.

The Philippines is the 9th country in the world with the most number of stunted children under 5 years old, according to Rappler. In 2011, 33.6% of children under 5 were stunted. From 2008 to 2011, stunting prevalence across all regions was never lower than 22%.

In his article, Murphy painted this painful reality: “Sadly, 12- and 13-year old girls in Tondo never have enough food and are much more like children than young women. There is never enough food in the homes of the poor. Mothers regularly slap the children to stop them from complaining about the lack of food on the table.”

Oftentimes, those living in rural areas have lower cash incomes compared with those from urban areas. But in matters of health, urban poverty is worse. Recently, the Environment and Urbanization Journal devoted a special issue on health and the city. The opening editorial said: “Most cities (in developing countries) fail to provide the most basic safeguards for good health, such as piped water in every house or at least in every neighborhood; toilets in every home; drainage in the streets (where stagnant puddles of water breed typhoid fever, cholera, and dengue fever); and emergency services, such as fire controls.”

THE LINGERING CAUSES

Despite the government’s efforts in eradicating poverty, the problem remains. Some say the government lacks political will while others contend there is too much graft and corruption among government officials. But there’s one clear reason why the country remains poor: a high population level. In 1980, there were 48 million Filipinos. In 2000, the number swelled to 78 million. By 2012, the population reached 93 million.

Given that the population of the Philippines is increasing at a rapid rate of 2.36% per year, it can be translated as an increase of more than 5,000 people daily. In 1985, the absolute number of people living in poverty was 26.5 million. This increased to 30.4 million in 2000.

“As the Philippines has financially limited resources and a high poverty rate, the rapid increase in population has become a problem because there is insufficient resource to support the population, which leaves much fewer means to improve the economy,” someone commented.

The Asian Development Bank, in its report, Poverty in the Philippines: Causes, Constraints and Opportunities, said the other main causes of poverty in the country are as follows: low to moderate economic growth for the past 40 years; low growth elasticity of poverty reduction; weakness in employment generation and the quality of jobs generated; failure to fully develop the agriculture sector; high inflation during crisis periods; high levels of population growth; high and persistent levels of inequality (incomes and assets), which dampen the positive impacts of economic expansion; and recurrent shocks and exposure to risks such as economic crisis, conflicts, natural disasters, and “environmental poverty.”

In terms of natural disasters, a report released by World Bank last year stated: “From 1990 to 2006, the country experienced record weather-related disasters, including the strongest typhoon, the most destructive typhoons, the deadliest storm, and the typhoon with the highest 24-hour rainfall on record.”

The World Bank report, “Getting a Grip on Climate Change in the Philippines,” added: “These events are projected to continue to intensify, requiring the Philippines to improve its climate resilience and develop its adaptive capacity to alleviate the risk of catastrophic economic and humanitarian impacts.” Filipinos may be resilient, but in the face of continuous disasters and poverty, they need help.

“There is a lot that happens around the world we cannot control,” American Congressman Jan Schakowsky once said. “We cannot stop earthquakes, we cannot prevent droughts, and we cannot prevent all conflicts, but when we know where the hungry, the homeless and the sick exist, then we can help.”