Marilyn C. was repeatedly raped by her stepfather when she was only 12. After months of abuse and threats to keep silent, Marilyn disclosed it to her mother who refused to believe her. She felt abandoned and unwanted and left her home in Mindoro, an Island south of Manila. She found a job peddling cosmetics door to door and was brought to Boracay where there are many night clubs and bars. There, she was commercially sexually exploited at 13.

She was approached by an employee of one of the bars who introduced her to Bernard, a French bar operator. He gave her a job, but a few days later, he raped her. Then she was given to his friends, other foreigners, and told that it was the only way to get ahead in life. She felt trapped: “I was helpless and had no resistance left. I was like a powerless slave to them. Outside, I showed submission, but inside I was full of anger and hatred. I couldn’t escape from the island and I endured such life. I could see no other alternative for myself. I had lost my dignity and self-respect and felt I was worthless and had nothing to lose because no one respected me and I had nowhere to go.”

One day, a sex tourist liked her, hired her out and brought her to Manila. After a few days, he got tired of her. Like a child, he became frustrated and angry. Marilyn was so scared that he would hurt her, but instead he went out and bought another street girl. Marilyn was on her own. She met another pimp, a Filipino woman, who offered her a job to escort tourists. She had with her a younger girl, 9-year-old Pia. Marilyn was introduced to a Dutch man, Lennard Van E. Pia was brought to Room 406 where a German, Thomas B., got in and abused her. The two girls stayed together with the two sex tourists in Manila and the abuse continued, watched over by the pimp nicknamed Lani, who was getting the money.

At the beginning of 1997, the two sex tourists brought the girls to Boracay. They rented two cottages near the beach. Thomas set up a video camera and video taped himself sexually abusing Pia with her hands and arms tied. He had a computer business in Iserlohn, Germany, and presumably he was interested in selling or swapping child pornography over the internet.

On the third day, the wife of the local mayor, alerted by the campaign about sex tourism, became suspicious of the two minors with the foreigners and called the police to investigate. They arrested Pia and Marilyn; Thomas and Lennard were allowed to go to their rooms giving them an opportunity to destroy all the incriminating evidence of their crimes by throwing the video tapes into the sea.

On January 11, the National Bureau of Investigation filed charges against Thomas and Lennard and they were jailed. The girls were placed in a children’s home in Iloilo run by the Daughters of Charity. The two suspects paid US$1,000 bail each and went free, despite the fact that the abuse of a child under 12 years of age is non-bailable. They got their passports back, too, and fled the country.

The news reached PREDA which filed charges against the suspects in Germany. The girls agreed to cooperate and to be transferred to the PREDA Children’s Home. It would have legal custody over them and would help them recover through therapy and counseling.

All the evidence available was sent to Germany. On August 23, Judge Vaupel of the regional court in Iserlohn near Dusseldorf issued an arrest warrant for Thomas. When the two girls had gathered enough self-confidence and emotionally ready, the court trial was set. They went along and testified without hesitation. No postponements were allowed. It was all over in three days. Thomas was pronounced guilty of sexual exploitation of a child while abroad under the little-used extraterritorial law. He received the maximum penalty under the law which was three-and-a half years with probation. Lennard was also found guilty in Holland and sentenced to one year. It was a moral victory for PREDA and especially for all abused children.

Soon after the trial, Marilyn and Pia settled down to rebuild their lives. Both went back to school while in the PREDA Centre and persevered in their studies. They became very outspoken lobbyists of children’s rights and made it their mission to use their experience to educate both adults and children about the dangers of the sex tourism business. They traveled to several countries giving talks and making media appearances. Marilyn completed her studies as a social worker, worked with the Department of Social Welfare and Development in Iloilo for almost 2 years and then returned to PREDA where she is helping abused and exploited children. Pia trained as a nursing aide and worked at PREDA for over 2 years. Then she went to Ireland for a one-year training and has since returned to work at PREDA.

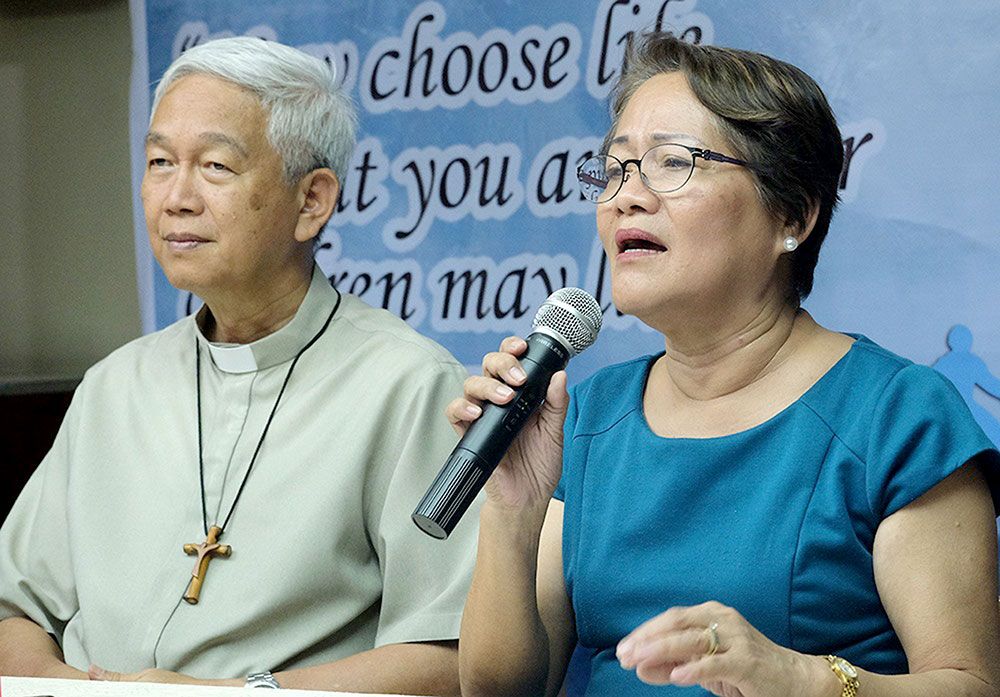

PREDA has five former sexually-abused or trafficked girls in the staff as counselors. “This is evidence of success, that our rehabilitation program does work in changing lives,” says Fr. Shay Cullen, who has been rescuing hundreds of kids from the grip of traffickers, pimps, nightclub operators and home harassers and giving them a new hope and a new life.

Growing business

The Philippines became a bustling sex destination with an estimated 1.2 million single male tourist arrivals per year. Internet played its part. A site (Balibago.com) announces: “You can enjoy full privileges with one or more attractive young females regardless of your age, weight, physical appearance, interpersonal skills, wealth or social class. Go-go bars start to open at noon and a few keep the music pumping until 5 a.m.. Some small hostess bars are open 24 hours. Prices are extremely low, which means you can carouse at full throttle without wiping out your life savings. English is widely spoken. You don’t have to learn a single word of the native language.”

The multi-million dollar fluid underground business is difficult to curb. Most bars, clubs, massage parlors, beer houses and karaoke bars are just fronts for prostitution. And many of them employ minors. Their documents are fake and rarely verified by officials.

Rescue operations do not always succeed for different reasons. The girls who have been brainwashed may not want to change life. The bar owners have managers handling the girls and they allow them to work in a particular bar for 3/4 months and prohibit them from going out during the day. Then they move them to another province. Often, they have good connections and enjoy police protection.

To cite an example: On December 27, 2008, PREDA’s rescue team went to Alaminos City (Pangasinan), some six hours away from Olongapo, to rescue three girls, two of them are sisters, 12 and 13 years old. With them were the mother of the girls, a government social worker and a police from the birthplace of the children (a legal requisite). The girls had been trafficked from Limay, Bataan to Alaminos and have been working as prostitutes in a videoke bar for some weeks.

Arriving at Alaminos, the team went to the police station. They were told to come back at night time. They suspected the police were hiding something, but they complied. Returning, they asked the police to let them go inside the bar first (to prevent the police from creating confusion and alarming the neighboring bars that could be employing minors). But when the PREDA team arrived at the scene, the police had been there and the children were nowhere to be found. Frustrated, the team searched for them in other bars. One hour later, the police called to tell them that they had found the children in the bus station. It was clear to the team that the policemen were friends of the bar owner and were protecting him from being charged.

Sickening reality

A rescue operation needs a lot of undercover surveillance and a lot of coordination with the police (whose report is needed to file a case before the court) and a social worker who has no criminal liability in taking girls out of houses and bars. Unfortunately, sometimes no social worker is available. The Police have the so-called Women and Children’s Desk, but, ironically, it closes at 5 p.m., when most violence against women and children happen at night.

PREDA conducts undercover surveillance in the bars to confirm reports made by anonymous people and to detect if underage girls are being used. Fr. Shay often poses as a customer. He challenges the ‘mama-san’ (the oldest lady in the bar) and/or the floor manager with the question: “Is it safe to have minors here?” The answer often sounds boastful: “Yes, it is safe. Do not worry. There’s no problem here. We have licenses, permits. The owner is a policeman or he is a good friend of Chief or General so and so…” Sometimes, besides aiding or abetting the crime of sexual exploitation of children, policemen own nightclubs and are part of the sex business.

Emmanuel Drewery, PREDA’s communications officer, is one of the staff who conducts undercover operations in red light areas to see if they employ minors. He explains how it is done. They talk to the pimp (on the street) or to the floor manager in the bar and look for young looking faces to invite them to sit at their table and buy them a lady’s drink. That’s the time they are able to interview the child. If they like to document what is going on, they use hidden video cameras. Considering the life of scantily-clad girls gyrating for customers, he sighs: “It’s a very sickening reality!”

They ask the kid’s name, where is she from, how long has she been working there… but do not ask her age because she will lie in order to protect the bar owner. The approach is to befriend her: “We try to make her feel comfortable. We behave as friends, not customers. Slowly, she is going to open up. We try to meet her when she is out of duty and we bring her to a fast food restaurant where we can talk. Only then do we open to her our real purpose and suggest our programs and services to help her come out, start a new life and have a future.”

He adds: “The girls are happy to have a free meal because their wages are normally very low: from 100 to 150 pesos per day, that’s lower than what a factory worker gets. Many are forced into prostitution by life circumstances: poverty or abuse. Many have been abused at home by their fathers, foster fathers, or other male family member. They ran away because they believe that they have no dignity anymore and nobody will accept them. Others wish to find a foreigner boyfriend who can give them a good future.”

Therapeutic intervention

A daily work of the paralegal team is to monitor PREDA’s hotlines through which people can report cases of child abuse. Some are reported through text messages, others by walk-in clients. Not all reports are authentic and all have to be verified. When they receive reports of abuse in homes, schools or somewhere else, a team, formed by a paralegal and a social worker, is dispatched to verify. They interview the child to verify if the report is credible. If the supervision is positive, the child and the parents are invited to come over to PREDA to be interviewed formally and to build a case.

The ideal is that abused children are admitted for therapeutic intervention because they feel unloved by the family and look down on themselves. A team of social workers and therapists cares for them 24 hours a day. They ensure the girls have formal education, a skill-training program, counseling, primal therapy to release their emotions and other activities to raise their self-esteem and regain self-confidence. They have regular Bible sharing and Mass on Sundays. Parents are invited to come and visit the child at PREDA during Christmas, the child’s birthday and other occasions to start the process of reconciliation and reintegration in the family.

While the children are there, PREDA provides for everything – board and lodging, education, enhancement of skills, therapeutic intervention… Often, they give financial assistance to their families so that they may start their own livelihood projects. Children are helped to experience a new way of life and a different way of looking at themselves. That helps to change their lives.

Legal Via Crucis

Meanwhile, PREDA provides legal assistance in filing court cases. Its paralegal team listens to the children, with the help of trained social workers, and makes the reports, submits them to the medico-legal examiner, enrolls the witnesses, prepares the affidavits, escorts the children to the prosecutors’ office, attends the hearing, files motions and manifestations when necessary… In short, they file the charges on behalf of the children and monitor them.

PREDA always goes after the crime perpetrators even if they are the family’s breadwinners. Otherwise, they might harass and sexually abuse other children in the family or find victims outside in the community. But it is hard to pursue justice on behalf of the abused children. Sometimes, they have to deal with uncooperative government officials; other times, children rescued from sex bars believe that that is their life; they become uncooperative victims who would rather abscond, get out of the Center and go back to the street or the bars. If they had been abused at home, they may deny to have been raped.

Robert Garcia, the head of PREDA’s paralegal team since 2000, summarizes what they consider meager prosecution achievements: “In my recollection, we only have 17 cases of conviction against Filipino perpetrators and another 7 against foreigners… from around 300 cases PREDA has handled since 1933. The rest were either archived, dismissed or the accused were acquitted.”

He admits that it is difficult to prosecute the owners of glitzy sex establishments like those in Angeles City, employing hundreds of girls, because some belong to corporations and it is hard to prove ownership or to prove the girls are minors. The only success there is when bars are raided and children are rescued through the instigation of PREDA undercover workers. Bars found with minors may be padlocked for sometime only to open again under a new name and management. The prosecution of breadwinners is difficult as well because the family, starting from the mother, tends to cover up the case.

On the other hand, the judicial system makes it difficult to get justice for the victims. Robert Garcia explains: “In the Philippines, we lack everything – courts, judges, prosecutors… At times, the cases take ages in court before the actual hearing. They can take from three to nine years before a decision is reached. And we are lucky if there’s a conviction.” The wheels of justice are too slow. Victims have to wait a few years for a court decision – if it ever comes. PREDA has to continue to protect and support the child all those years especially when the abuser is out there waiting for the child to come home. Then he can abuse her again or intimidate her to drop her complaint.

PREDA is too dependent on the public prosecutor; it does not have money to engage a private lawyer for the many cases, since he is very expensive. No lawyers offer service pro bono just to help child victims because they are too busy making money. On the other hand, some perpetrators can hire good lawyers to protect themselves and file countercharges against PREDA. When they rescue a child, sometimes they are charged with kidnapping; when they report a case of child abuse, they may be sued for libel.

Other times, the perpetrators go after the witnesses and complainants to silence them because without them there will be no case. To apprehend the suspects, therefore, is important. Even when the victim is able to file a case and it reaches the court, but if the suspect is at large, the case could be archived – until the time the perpetrator is arrested. There is no sufficient police to look after each individual case and, often, they do not care to serve the arrest warrants, says Garcia.

When an abused girl is reintegrated into her home and the suspect is still at large, it sometimes happens that, she, enticed by the family that is more supportive of the incestuous abuser than of her, files an affidavit of desistance dropping the charges. The challenge for PREDA is to help her to finish her testimony as soon as possible so that the case can proceed. After the child has finished her testimony, the case can go ahead because there is a DOJ (Department of Justice) circular that forbids a case being withdrawn due to an affidavit of desistance. However, this is ignored at times if the prosecutor wants to please the accused.

PREDA’s paralegal team is handling 107 legal cases right now. Many are of children who have already been rehabilitated and reintegrated into their families but are still seeking justice. This means the rehabilitation is over but not the legal case. After reintegration, the children still receive assistance for another 18 months. But even after that period, PREDA continues providing transportation allowance to them for court hearings, and monitoring the cases until they are finished.

According to Fr. Shay, “what is needed by all is a commitment to justice, to the dignity of the children and, for those who believe in Christianity, to practice it.”