The Mariana Islands is a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen mostly dormant volcanic mountains in the western North Pacific Ocean. It lies south of Japan and east of the Philippines, demarcating the Philippine Sea’s eastern limit. The Islands was named after Queen Mariana by the Spaniards who first arrived in the early 16th century and who eventually annexed and colonized the archipelago. The previous name was Islas de los Ladrones (Islands of the Thieves).

The indigenous inhabitants are the Chamorros. Archaeologists in 2013 reported that the people who first settled in the Mariana arrived there after making, what was at that time, the longest uninterrupted ocean voyage in human history. Findings further suggested that the island of Tinian is likely to have been the first island in Oceania where humans have settled.

In 1668, Pedro Calungsod, a 14-year-old teenager, was among the exemplary young catechists from his native Visayas region chosen to accompany the Spanish Jesuit missionaries to the Islas de los Ladrones. Calungsod went with Fr. Diego San Vitores to Guam to catechize the native Chamorros. Missionary life on the island was difficult as provisions did not arrive regularly, the jungles and terrain were difficult to traverse, and the Mariana was frequently devastated by typhoons. The mission, nevertheless, persevered and a significant number of locals were baptized

After a while, a Chinese man named Choco, a criminal from Manila who was exiled in Guam, began spreading rumors that the baptismal water used by missionaries was poisonous. As some sickly Chamorro infants who were baptized eventually died, many believed the story and held the missionaries responsible. Choco was readily supported by the macanjas (medicine men) and the young warriors who despised the missionaries.

Supreme Sacrifice

On April 2, 1672, Calungsod and San Vitores came to the village of Tumon. There, they learned that the wife of the village’s chief, Matapang, had given birth to a daughter, and they immediately went to baptize the child. Influenced by the calumnies of Choco, Chief Matapang strongly refused. To give him some time to calm down, the missionaries left his house and gathered the children and some adults of the village at the nearby shore and started chanting with them the tenets of the Catholic faith.

They invited Matapang to join them but he shouted back that he was angry with God and was fed up with Christian teachings. Determined to kill the missionaries, Matapang went away and tried to enlist another villager, a pagan named Hirao. The latter initially refused, mindful of the missionaries’ kindness towards the natives but became irritated and, eventually, relented when Matapang branded him a coward.

While Matapang was away from his house, San Vitores and Calungsod baptized the baby girl, with the consent of her Christian mother. When Matapang learned of his daughter’s baptism, he became even more furious. He violently hurled spears, first at Calungsod who was able to dodge them. Witnesses claim that Calungsod could have escaped the attack but did not desert San Vitores. Those who personally knew Calungsod were aware of his martial abilities and that he could have defeated the aggressors with weapons. However, San Vitores had banned his companions from bearing arms.

Eventually, Calungsod was struck in the chest by a spear and fell to the ground, then Hirao immediately charged towards him and finished him off with a machete blow to the head. San Vitores quickly gave absolution to young Pedro Calungsod, then he too was killed.

Matapang took San Vitores’ crucifix and pounded it with a stone while blaspheming God. Both assassins then undressed the bodies of Calungsod and San Vitores, tied large stones to their feet, and brought them on their boats out to Tumon Bay, dumping the bodies in the water.

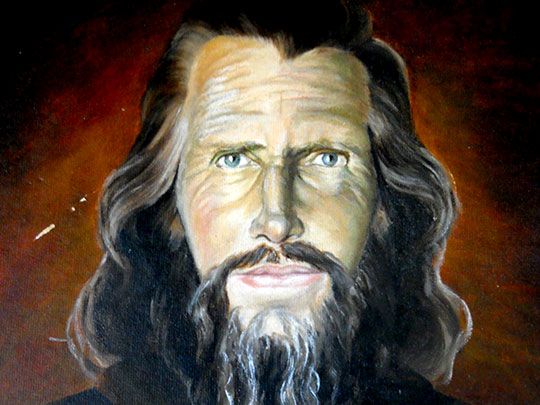

We know nothing of Calungsod’s beginnings. Only the adjective “Visaya” that accompanies his name tells us that he was from Cebu. It is probable that he received basic education at a Jesuit boarding school, mastering the Catechism and learning to communicate in Spanish. He also likely honed his skills in drawing, painting, singing, acting, and carpentry, as these were necessary in missionary work. Pedro Calungsod was beatified on March 5, 2000 by Pope John Paul II and canonized by Pope Benedict XVI at Saint Peter’s Square in Vatican City on October 21, 2012.

Blood as seed

On the occasion of Pedro Calungsod’s beatification, Pope John Paul II said: “From his childhood, Pedro Calungsod declared himself unwaveringly for Christ and responded generously to His call. Young people today can draw encouragement and strength from the example of Pedro, whose love of Jesus inspired him to devote his teenage years to teaching the faith as a lay catechist. Leaving friends and family behind, Pedro willingly accepted the challenge put to him by Fr. Diego de San Vitores to join him on a mission to the Chamorros.

“In a spirit of faith, marked by strong Eucharistic and Marian devotion, Pedro undertook the demanding work asked of him and bravely faced the many obstacles and difficulties he met. In the face of imminent danger, Pedro would not forsake Fr. Diego but, as a “good soldier of Christ,” preferred to die at the missionary’s side. Today, he intercedes for the young, in particular those of his native Philippines, and he challenges them.” John Paul II concluded: “Young friends, do not hesitate to follow the example of Pedro, who “pleased God and was loved by him” (Wis 4: 10) and who, having come to perfection in so short a time, lived a full life (Wis v. 13).”

On December 19, 2011, the Holy See officially approved the miracle qualifying Pedro Calungsod for sainthood by the Roman Catholic Church. The recognized miracle dates back to March 26, 2003, when a woman from Leyte, who was pronounced clinically dead by accredited physicians two hours after a heart attack, was revived when an attending physician invoked Calungsod’s intercession.

On October 18, 2012, several hundred pilgrims from the Philippines gathered in the Church of St. Augustine in Rome for a Mass celebrating the life of Blessed Pedro. Among the prelates concelebrating at the Mass was Msgr. Anthony Apuron, Archbishop of Agana in Guam, the island where Blessed Pedro was martyred. He was asked: “How do you feel about the canonization of Blessed Pedro Calungsod?” Archbishop Apuron said: “I think it’s a moment of pride. I know for the Filipinos, and especially those in the Visayan region, and just today before the Mass, several of the bishops said: “We should really thank you; you should not apologize for the Chamorros, your people, killing Pedro Calungsod but, instead, we should thank you for giving us a saint.”

He was asked another question: “Tertullian, one of the early Church fathers, wrote: ‘The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.’ Since Blessed Pedro was martyred in Guam, have you seen the fruits of this seed? Has this seed been planted in Guam?” This is his answer: Yes, we now have native vocations. I started a major seminary and I’ll be ordaining my eleventh priest this coming November. Other six native seminarians are there and one of them hopefully, next year, will be ordained a deacon. So, vocations are coming and I think the Church is still going strong in Guam after more than 300 years of Christianization, so the Church will survive.”

In Calungsod’s footsteps

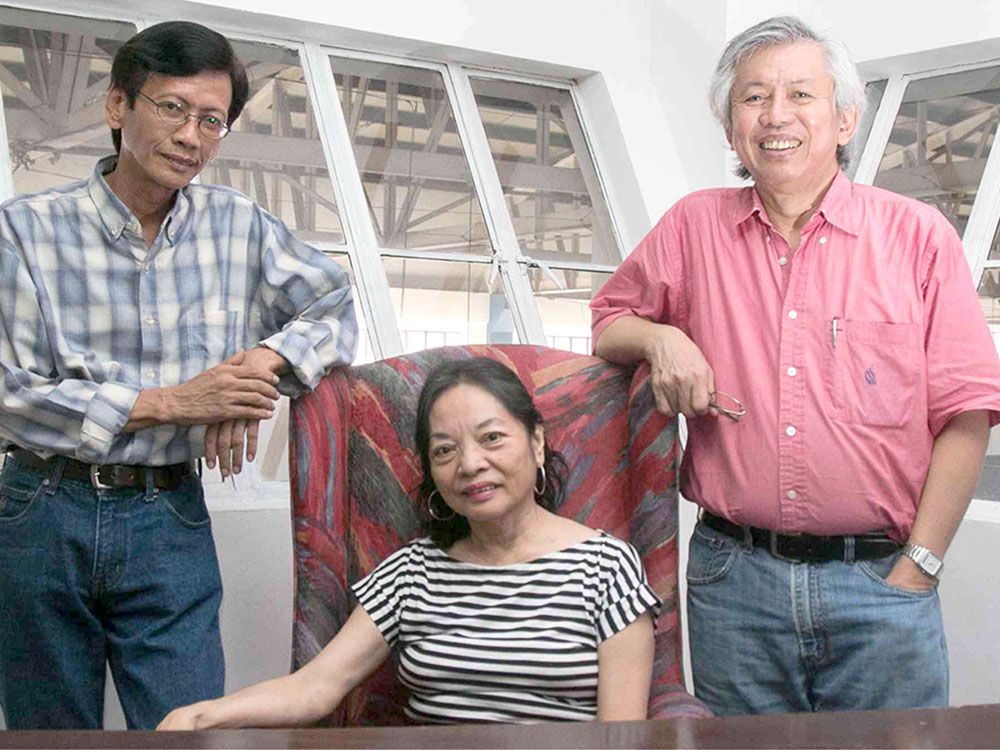

On February 11, 1915, Feast of the Apparitions of Our Lady at Lourdes, two Italian Comboni missionaries arrived at Kitgum, the main town of that area, in Northern Uganda, East Africa. They settled in the midst of the Acholi people, “around the fire” as they say there, to listen, converse and announce the Gospel. Among the first youth who were baptized were two teenagers, Daudi Okelo and Jildo Irwa who subsequently accepted the invitation of becoming catechists and were sent to a fairly distant area, called Paimol, to instruct the people in the new religion.

After a successful beginning, when the local population had already appreciated their presence, violent opposition appeared on the part of the witch doctors and some Muslim traders who accused the new religion of the calamities, like drought and epidemics, that were affecting the people. On the morning of Sunday, October 20, 1918, Daudi and Jildo were speared to death. Their bodies were abandoned in the grass until a merciful hand gathered their remains and took them to the parish of Kitgum where they had been baptized. The two boys were 18 and 16 years old, respectively.

Daudi Okelo and Jildo Irwa were beatified in Rome on Mission Sunday, October 20, 2002, by Pope John Paul II. They followed in the footsteps of Pedro Calungsod. They are symbols of the catholicity of the Christian faith. They reminded those who wanted to kill them that no one would ever be able to bar the door to Jesus Christ.

Today, thanks also to them, Uganda definitely belongs to Christ: Christians make up 70% of Uganda’s 25 million people. The best fruit of their martyrdom has been a host of catechists in Northern Uganda. Many of them have sealed the announcement of the Gospel with their blood. In the Diocese of Gulu alone, to which Kitgum belongs, at least 80 catechists have been killed in the past twenty troubled years.

The Archbishop of Gulu, Right Reverend John Baptist Odama, wrote in the letter of preparation for their beatification in Rome: “The two martyrs died to bear witness to what they had encountered and had made their life free and full. A life that rose upon two pillars: passion for Christ and love for our Lady. The encounter with Christ made them more human, thus they bore witness to how precious this treasure they had encountered was to them, to the point of giving their life for it.”