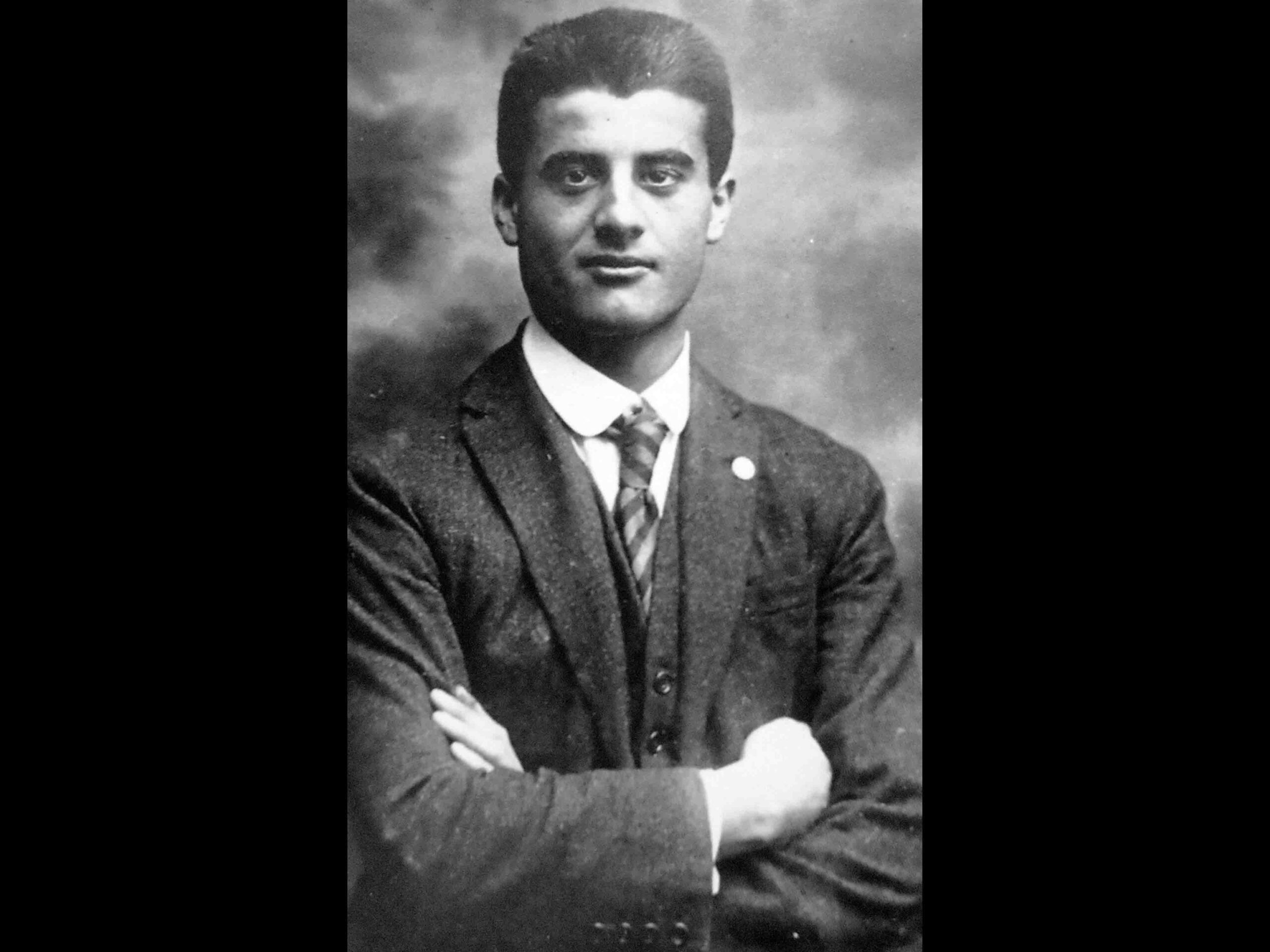

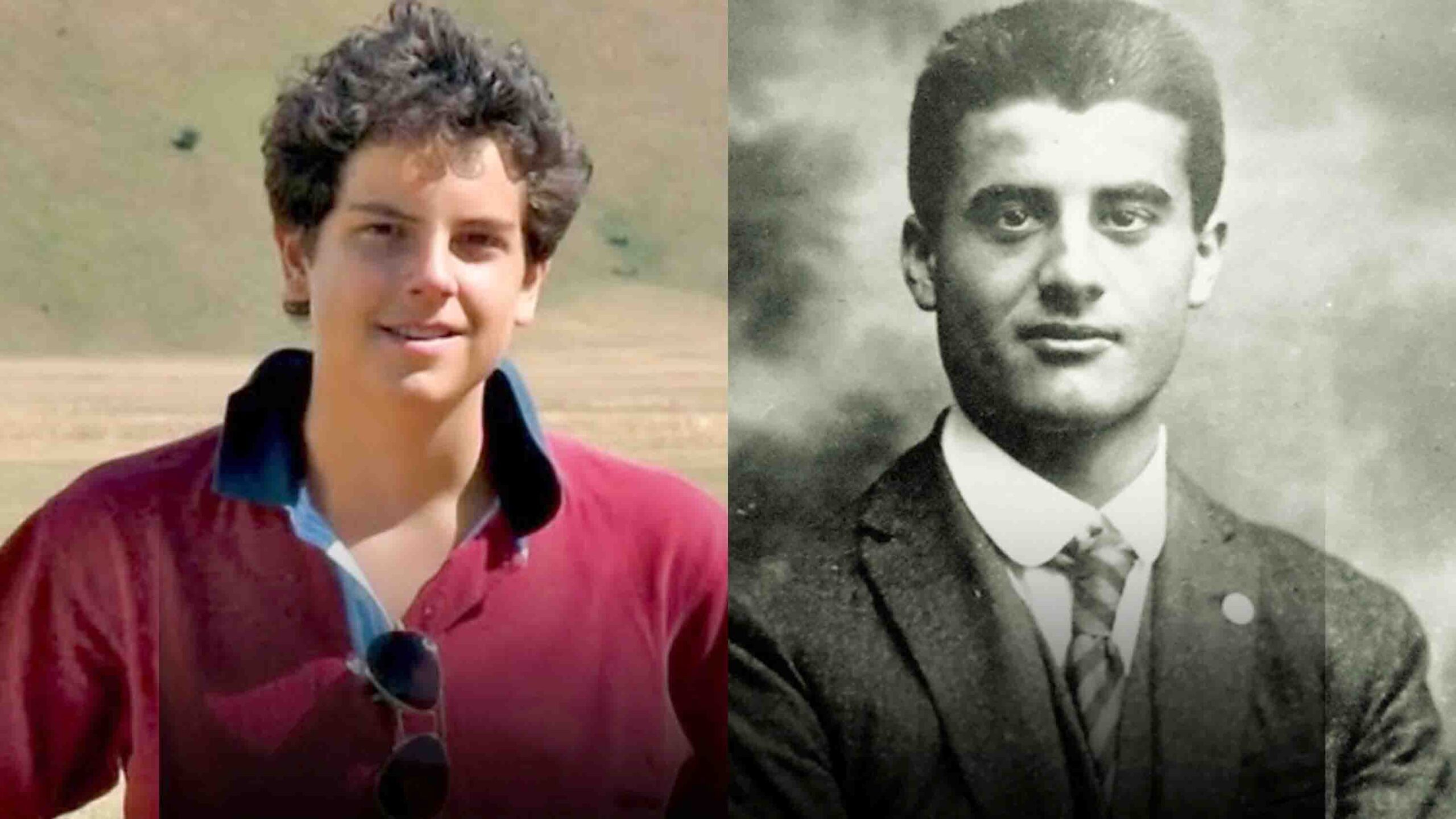

Pier Giorgio Frassati was a golden boy. Born into a well-off family in April 1901, he seemed blessed with the proverbial silver spoon in his mouth. His father, Alfredo, owned the famous Italian newspaper La Stampa, served in the Italian Senate, and was Italian ambassador to Germany. His mother, Adelaide, was an artist whose works were sought after by Italian royalty.

One can imagine that such a child, with only one sibling (a sister born in August 1902), could have grown to be a spoilt brat. Instead, he was generous with all that he had. He gave the very shoes off his feet to a woman begging with her barefoot child, and persuaded his mother to care for a drunk man who turned up on the Frassati doorstep.

Nonetheless, a Catholic influence saw him receive his first Holy Communion in 1911.

Young Frassati seems to have been a bit of a class joker, which led to him failing his exams. He was then sent for private tuition to a Jesuit school. Perhaps this Jesuit influence shaped what he would become in his teens and early twenties.

His track record is one that most teenage boys and young men will never achieve, yet. At the same time, we read his inspirational words and note his close following of the Beatitudes (St. John Paul II called him “The Man of the Eight Beatitudes”), there is an overriding impression that he exuded the notion that he was “just one of the boys”.

A JOYOUS ‘NORMAL’ YOUNGSTER

One hundred years after his death, today’s young people are on record saying that he inspires them because he was just like them; that “saints” aren’t usually as “normal” as Frassati. Perhaps we read too much into what other saints may have been like: if Gen Z and Gen Alpha had been contemporaries of St. Francis, for example, they may have found him inspirational in his normality and extraordinariness.

So perhaps we need to look more deeply into Frassati’s extraordinariness–and rest assured, he was indeed extraordinary. So extraordinary that two Popes have noted what an inspiration he is for young people.

The late Pope Francis placed him among the twelve exemplary saints for all young people in his apostolic exhortation, Christus Vivit, among those “who devoted their lives to Christ… precious reflections of the young Christ.” He added, “their radiant witness encourages us and awakens us from our lethargy” (CV, 49). Pope Francis also echoed St. John Paul II when he said that Frassati “was a young man filled with a joy that swept everything along with it, a joy that overcame many difficulties in his life” (CV, 60).

The choices he made in his life have the power to “awaken us from our lethargy.” Firstly, there was his spiritual life. If we remember that his father was an avowed atheist, it is most likely that he was sent to the Jesuit school simply to get better exam results. But he was clearly open to all that Catholicism had to offer and joined the Marian Sodality and the Apostleship of Prayer.

At a time when it was rarely permitted, he impressed the clerical hierarchy sufficiently to allow him to receive daily Communion. The fact that he sought this as a teenager is evidence of the depth of his faith. Nor was he reticent about sharing that faith with his friends.

When he was 17, he joined the St. Vincent de Paul Society, and his free time was spent serving the sick and those in need, caring for orphans, and returning World War I soldiers.

He studied to become a mining engineer at the Royal Polytechnic University of Turin. He was not following in either Dad’s or Mum’s footsteps, but he confided in a friend that he could “serve Christ better among the miners.”

He joined the Catholic Student Foundation, but to be able to take part in political activism, he also became a member of a group called Catholic Action. This was after all the young man who had said, “Charity is not enough; we need reform.” And to underpin all of that, he became active in the People’s Party which promoted the Catholic social teaching that followed Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Rerum Novarum.

CARE FOR THE POOR

He gave of his cash, and he gave of himself. The family owned a holiday home at Pollone in the countryside near Turin, to which Alfredo and Adelaide escaped from the summer heat whenever duties related to politics and journalism allowed. Their son didn’t join them, devoting himself instead to caring for the marginalised, the poor, and the sick. Of the summer exodus from the city, he said, “If everybody leaves Turin, who will take care of the poor?”

However, he did have his own hiding place from the city. Frassati was a skilled mountaineer, swimmer and athlete (according to some stories he would give someone in need his own bus fare and then run home to be on time for family meals). He climbed mountains such as the Grand Tournalin (3,379 metres or 11,086 feet) and Monte Viso, which is the 10th highest mountain in the Alpine range, and invited friends along on what seemed to occasionally become spiritual retreats. But, as regards “normality,” he also enjoyed the theatre and films that met the standards of his moral code.

It is ironic to note that he wouldn’t go to a movie if there was any suggestion of it being less than “proper,” because rumours had it that he had behaved with impropriety which delayed the progress of his sainthood. This gossip surfaced not in the immediate aftermath of his death when the religious process began, but a full sixteen years later in 1941 when it was suggested that those trips to the mountains had a less than moral intention.

At the time, everything was thrown off course, and it was Frassati’s sister who persuaded the Church authorities to continue the process of his canonisation, reassuring them that every acquaintance of his recognised that these mountaineering expeditions were beneficial to the minds, bodies and souls of all who accompanied him.

Today such malicious gossip is the kind of thing we might see–even expect to see–on social media; it would be dismissed as spiteful trolling. In 1941, letters or statements that suggested a candidate for canonisation was less than perfect caused major upset.

ENCOUNTER WITH ‘SISTER DEATH’

Returning to the reasons for Frassati’s potential canonisation: what happened to this amazing young man who was living life to the full in the most Christian way possible? You need to die first to be considered for sainthood.

One might imagine that he had ventured into a poor area of Turin to offer help to someone in need and was fatally attacked. Or perhaps that he was killed whilst taking part in an anti-Fascist rally. Instead, it was in the wake of a boating expedition on the River Po that he fell ill. We know today that the polio virus can be transmitted through contaminated water, and a river such as the Po in the early 20th century would have been a source of such contamination.

On June 30, 1925, Frassati experienced a severe headache, back pains and a fever after his boat trip with friends. He kept these symptoms to himself because his grandmother had died that day, and he didn’t want to add to his mother’s emotional burden. It wasn’t until July 2 that a doctor had to be summoned because he could not get up. Paralysed by polio, he died on July 4, having given his final instructions to his sister and receiving the Last Rites. As he breathed his last breath in his mother’s arms, he said, “May I breathe forth my soul in peace with you.”

Thousands of people lined the streets when his funeral cortege passed on its way to the Frassati family mausoleum in Pollone. These were the people who soon began to petition for this young man to become a saint. By 1932, the Church had decided to begin the process of canonisation, and by 1938 there was agreement on all fronts that Pier Giorgio Frassati had met all the appropriate criteria, including a miracle occurring after his death. In spite of the hiccup in 1941 related to the malicious accusations that his trips to the mountains took place in mixed and dubious company, Frassati was proclaimed to be Venerable on 23 October 1987, when Pope John Paul II issued a decree confirming that he had lived a Christian life of “heroic virtue,” a concept required for beatification.

By that time, his remains had been removed from the family vault and placed in the Turin Cathedral. When they were inspected, they were found to be incorrupt. Incorrupt in life, incorrupt in death, this “Man of the Eight Beatitudes” will indeed be an inspirational addition to the canon of Saints.