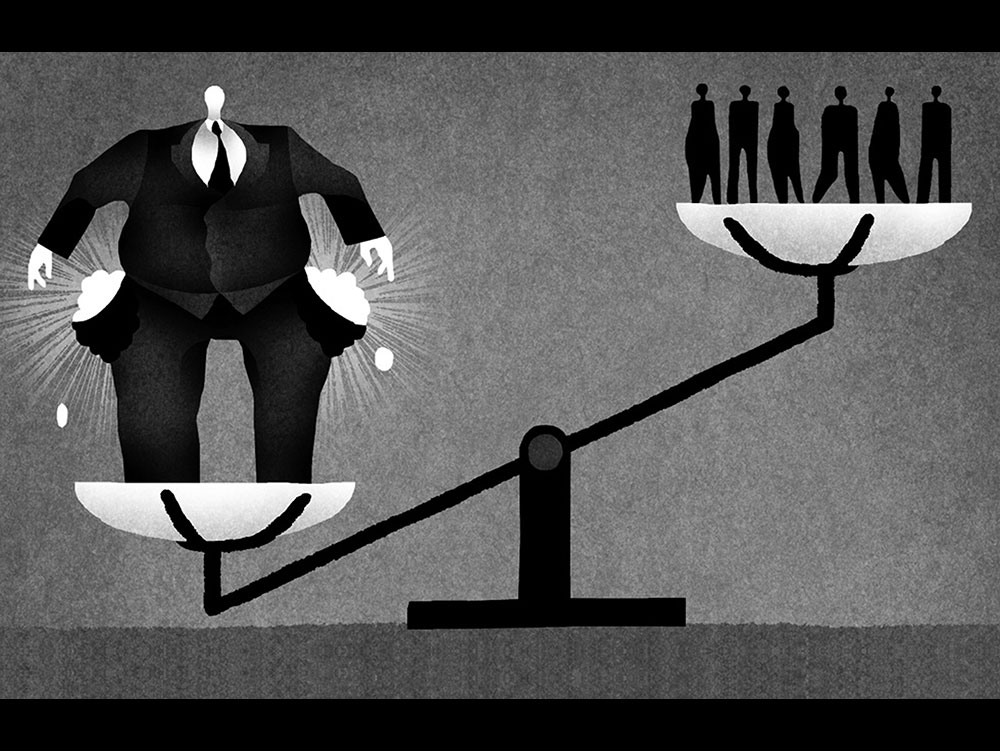

Various forms of international intervention in the affairs of African countries delegitimize local governments and disempower the people. One major example is the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), which have often been imposed by the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank as a condition for development assistance or the reduction of international debt. Often, the SAP entails a drastic reduction in public services to the poor, such as health care, education and transportation subsidies; it imposes the devaluation of the local currency and privatization of public services and state-owned industries. Trade liberalization goes hand in hand with SAPs. The debtor nation is forced to export raw materials and agricultural products in competition with other African countries that export the same items. Together with stock market speculation, this competition lowers commodity prices to the benefit of international trading partners and the detriment of the local people.

Within Africa, the immediate consequences are spiraling inflation on basic items including food, lower wages, increased unemployment and a much lower standard of living for most of the population. SAPs have contributed to the widening gap between “the haves” (mostly those with political connections) and “the have-nots” (those without political connections) as well as to increasing tension between people and their governments. The privatization of health care in African countries has resulted in a reduction in preventive community care and increased rates of illness and mortality. Ghana lost 300,000 public sector health workers in 16 years as a result of SAPs.

In many countries, the SAP was accepted and implemented by the political elite without consulting the people; only the elite and their external collaborators benefit. Through discount privatization, multinational corporations and the local elite literally buy the government in some countries and diminish the state’s capacity to provide fundamental public services to its citizens; this severely weakens the citizens’ capacity to meet basic needs and increases tension with the government. A systemic change is needed to reverse the situation. This can be achieved by engaging citizens in shaping their future and how they want to relate to other political entities and multinational corporations. Africa needs water, sanitation, schools, universities, medical hospitals and clinics, roads, bridges, transportation services and other infrastructure to empower its youthful work force and build a future. SAPs privatize much of this infrastructure and discourage government expenditure for the rest, so that only a minute elite benefits.

THE MINING WARS

Illegal mining and theft of resources are other big problems. Some countries are rich in minerals that are coveted by their neighbors and by multinational corporations. For example, North and South Kivu on the Eastern side of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) are rich in agricultural products, hard woods, water and minerals, such as gold, coltan (columbite-tantalite), cassiterite. Rwanda and Uganda have both invaded this area in the past to remove it from the control of the DRC government. Now they sponsor armed “rebel” movements, such as M23, to destabilize the area, and to illegally mine gold and coltan, using slave labor, including child labor. In this way, Rwanda is able to export a huge percentage of the coltan on the world market, although Rwanda has little of its own. Eighty percent of the world’s known coltan deposits lie in the DR Congo, and 90% of the minerals exploited in the Kivu are “exported” through Rwanda. The Eastern DR Congo is also rich in diamonds, copper, cobalt, tin, tungsten, chromium, germanium, nickel, zinc, manganese and uranium. In 2012, the Rwandan Army was gaining $250 million a month from the sale of these items. The industrialized nations that covet these minerals often turn a blind eye to how they are extracted. In this way, the possibility of national good governance in the DRC is undermined by regional and international interests that employ proxy forces and do not hesitate to foster armed conflict. Trafficking military weapons is often directly related to these proxy conflicts and contributes enormously to the instability of African countries and to the high mortality of civilian populations.

Armed “rebel” factions, such as M23 in the DR Congo and the infamous Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), routinely abduct children and force them to be soldiers. However, some African governments also have child soldiers in their armed forces. In Chad, armed rebel groups had the greatest number of child soldiers, but the national army also had many. In 2011, Chad signed an agreement with the U.N. to release all child soldiers. Angola, Central African Republic, Burundi, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mozambique, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Somali, Sudan, Uganda, Zimbabwe and DR Congo all had child soldiers in both military forces and rebel groups during their civil wars. The children who survived have been cheated of an education and are often traumatized and uprooted from their families. Recruiting child soldiers robs a country of future peace and development.

THE ROLE OF THE CHURCH

Both Special Assemblies of the Synod of Bishops for Africa (1994 and 2009) identified and addressed the social and political realities of Africa, including corruption and other problems of governance. “A serious reawakening of conscience linked to a firm determination of will is necessary in order to put into effect solutions which can no longer be put off” (Ecclesia in Africa, 1995, #110; cf. also 111–114).

Meanwhile, Bishops’ Conferences and regional organizations have become more outspoken. In February 2013, the Symposium of Episcopal Conferences of Africa and Madagascar (SECAM) released a long pastoral letter entitled “Governance, the Common Good and Democratic Transitions in Africa.” The pastoral letter notes that good governance is part of the common good that all must serve. It demands a greater opportunity for local communities and civil society to participate effectively in decision-making processes and encourages Christians to act with honesty, sincerity, inclusiveness, tolerance and a spirit of service. A “dynamic and functioning partnership between the various social actors (will) enhance transparency, efficiency and effectiveness of political action and decisions of public administrations.”

Noting the enormous gap between the wealth of Africa and the poverty of its people, SECAM urges Africa’s leaders to make poverty eradication a priority, so that all may benefit. This implies putting an end to corruption and having “free, fair, transparent and peaceful” elections. Calling all to take personal responsibility and act effectively, SECAM commits the bishops of Africa to the spiritual, ethical and practical formation of church members and small Christian communities on the basis of the social teaching of the Church.

In October 2013, the Southern African Catholic Bishops’ Conference issued a pastoral letter: A Call to Examine Ourselves in the Widespread Practice of Corruption. The bishops condemned the corruption that hurts the whole community, but especially the most defenseless, and presented ways in which ordinary people can resist corruption.

For this reason, the Africa Faith and Justice Network, in partnership with the Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies at the Catholic University of America in Washington, is working with SECAM and with African regional offices of justice, peace, development and good governance on a “democracy and empowerment project” to develop and promote “effective and sustained grassroots education, based on Catholic social teaching.” The goal is to promote awareness of the rights and responsibilities of citizens so that the peoples of Africa will be better empowered to transform their social, political and economic environment and to promote strong social and political institutions. Africa needs strong civil societies. The Church is a social and “political” actor with a vast network of members and institutions equipped to educate, conscientize and mobilize the public to work for the common good of all the people.

Part 1 of this article, was based on a presentation by Fr. Aniedi Okure, Executive Director of the Africa Faith and Justice Network in Washington DC, focused on problems in Africa related to faulty governance and the exclusion of people from participation in the political process. This article highlights a few more problems.