In his book No Future Without Reconciliation, Archbishop Desmond Tutu holds that post-conflict situations where the society is torn apart by hatred and a thirst for vengeance must strive towards mutual forgiveness for peace and stability to reign.

Pope Francis closely associates reconciliation with the redemptive mission of Christ who empties Himself to save humanity. The Pope states that “reconciliation is the re-creation of the world, and the most profound mission of Jesus is the redemption of all of us sinners. And Jesus did not do this with words, with actions, or by walking on the road, no! He did it with his flesh.”

On the other hand, Everett Worington Jr. defines reconciliation as “the restoration of trust in a relationship where trust has been violated, sometimes repeatedly. Reconciliation involves not just forgiveness but also many other ways of reducing un-forgiveness.” Reconciliation is therefore a relationship-building process grounded on a restorative approach to justice.

Four key preliminary steps ought to be undertaken in preparation for reconciliation. First, an in-depth contextual analysis on the diverse dimensions of the conflict or problem at hand. The contextual analysis takes into account the trends and patterns of conflict from a historical perspective while understanding the diverse internal and external factors that impact the presentation of the conflict. Second, is the analysis of the key actors involved in the conflict, particularly, the persons most responsible for particular acts of injustices, as well as the victims. The third is to understand the points of contention, grievances, and disagreements that led to the conflict or continue to trigger the conflict. Fourth, is to explore the various options available for the way forward, including forgiveness, reconciliation, restorative justice, and retributive justice.

The above four prerequisite leads set the ground for a deeper process of reconciliation that is contextually informed and sequentially ripe for the parties in conflict to engage.

Thorny Path

Generally, reconciliation, as a process, is never expected to be smooth and tranquil. It can be seen as a coalition of the opposites, an integration of opposed parties, a convenient co-existence, a mutual tolerance for a peaceful settlement, or at its most ideal–the embracing of the other with an open heart of forgiveness, respecting the dignity of the other.

It is this ideal that the psalmist thirsts for and proclaims that “unfailing love and truth have met; righteousness and peace have kissed!” (Psalm 85:10). Isaiah’s vision seeks more, stating that, “The wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatted calf together, and a little child shall lead them” (Isaiah 11:6).

This radical approach to a reconciled world, not only for humanity but nature as well, is the ideal proclamation of reconciliation. However, humanly speaking, reconciliation is often a thorny process that moves through five main stages.

Stages Of Reconciliation

First, is the willingness of the parties in conflict to sit and discuss the possibility of mending their relationships. This may involve a third party that may be assigned to persuade the actors in conflict to come to the dialogue table. In the African cultural settings, these could be elders who would have the responsibility of getting in touch with the different family or clan members or other ethnic elders to agree on the mediation and negotiation process.

In political settings, the process could be a bit more complex and may involve shuttle diplomacy between different parties. This could be through a government-appointed official who is assigned to engage with different parties in conflict within a country. Diplomatic processes may require a very complex skill of persuasion to get, for example, armed rebel groups to the negotiation table. Religious leaders can also be instrumental in negotiating with reluctant parties to bring them to the dialogue table. This is because they are often respected in the community, and seen to be neutral agents.

Second, is that once the parties agree to a dialogue process, they would be encouraged to bring forward their grievances and differences with each other. These will be analyzed and assessed to allow the parties to agree to the dialogue process. During this stage, each party will present their case while the other listens. The mediator will have the arduous task of drawing different presentations together to agree on the key issues to be addressed. Once these issues have been identified, the participants can prioritize them and/or discuss them in random order.

It is, however, important that the issues are prioritized and discussed one by one. There could be disagreements on the accuracies of the presentation of matters, including accusations and counter-accusations. It is the role of the mediator to make sure that the discussion does not escalate to further conflict. Once there has been an exchange on the key issues of concern, the mediator would encourage the parties to suggest possible ways of addressing the issues.

Third, is the dialogue on solutions to the conflict, which can be very difficult and may require a lot of persuasion and conviction of the parties. In most African contexts involving family or inter-communal conflicts, elders tend to refer to particular customs and cultural rules and regulations that may have been violated.

In their wisdom, the elder may deliberate about the issue on the spot and make a verdict. Alternatively, if the matter is too complex, they may refer to the civil authorities. In political dialogue processes, the parties involved in peace dialogue often want the assurance that any proposed agreement will be sustainable and that there will be no vindication against particular individuals who may have caused harm against the other.

However, that is a difficult balance to strike since governments operate under the rule of law, and unless there is an amnesty provision, there could be legal grounds for prosecution. If not handled properly this may lead to further escalation of the conflict.

The fourth step, after solutions have been proposed, is forgiveness. Oftentimes, forgiveness may take much longer to realize, because the parties may simply prefer an agreeable solution without necessarily getting to the level of forgiveness. This tends to be the case in situations of retributive justice where a judge or arbitrator makes a decision. However, in restorative justice situations, the focus is much more on building relationships, and the perpetrator has to acknowledge the guilt while the aggrieved advances forgiveness.

Fifth, is the reconciliation process where parties in conflict come together and commit themselves to live together in peace. In the African cultural setting, this may involve a formal process of a cleansing ritual, inviting the parties to forgive each other for peaceful co-existence thereafter. The perpetrator may be cleansed of his past offenses and be freed from any harm by bad spirits.

The victim, on the other hand, may be cleansed of all the misfortunes that could have befallen him/her or his/her family. The perpetrator may be required to compensate the victim through an agreed measure of reparation. Often, reconciliation ritual ends with a meal between families and clans of the victims and perpetrators.

Political Reconciliation

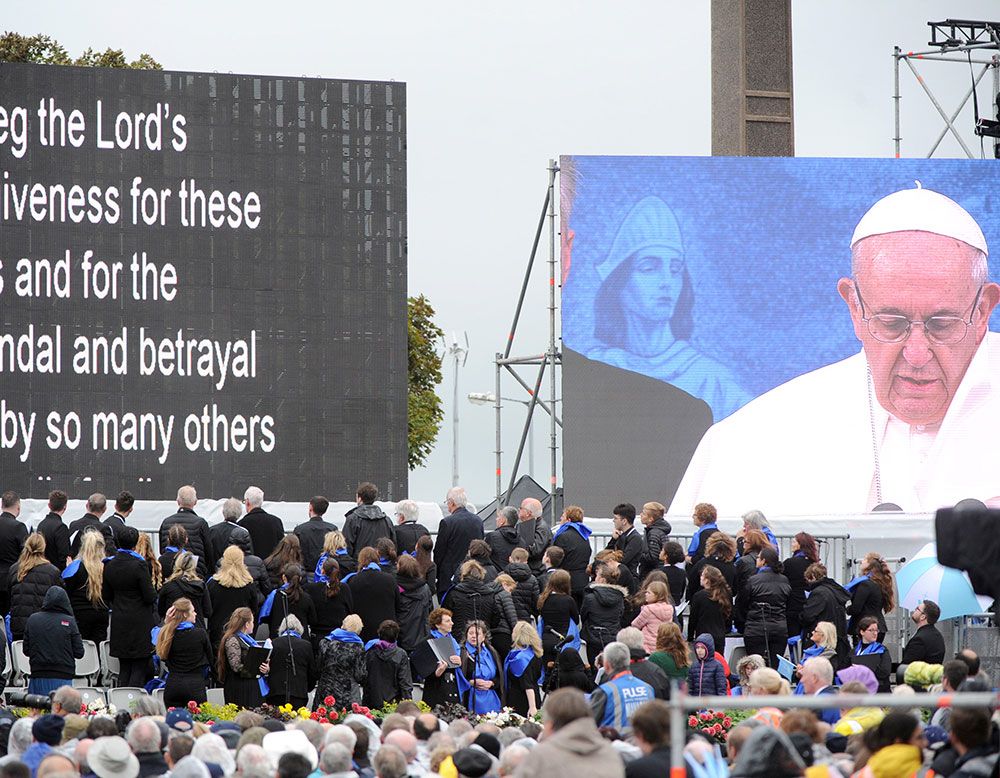

In political reconciliation, the peace dialogue process tends to end with the signing of a peace agreement and shaking of hands. However, for reconciliation to take place effectively, it is important to institutionally incorporate a political reconciliation process.

Political reconciliation looks into bringing the concept of reconciliation within a political domain. Some scholars contend that reconciliation is in itself political and not just one option among the many available to resolve political conflict. Within the political sphere, reconciliation and justice ought to be pursued concurrently to avoid future recurrence of conflict.

However, there has to be a point of negotiation, compromise, and forgiveness for such a political process of reconciliation to succeed. Adrian Little and Sarah Maddison argue that both concepts are intertwined citing Stephanus du Toit’s suggestion that “the paradigm of reconciliation provides an ‘interpretative framework’ for the ‘inclusive implementation of human and/or constitutional rights.”

Hence, reconciliation as a process is complex and ought to be understood from a multifaceted perspective, whether religious, political, cultural, social, or economic. The success of any reconciliation process will very much depend on the social resources in place, the capacity of the leaders and mediators to persuade parties in conflict to come to the dialogue table, and sustainability of the agreed tenets of peace agreements, forgiveness process, and eventual reconciliation affirmation by the parties.