When asked about the images of God they see around them, many people point to the crucifix, icons, and other blessed representations of God the Father, Jesus, or the Holy Spirit in churches or homes. Others, on the other hand, look up to the Pope, bishops, and priests as images of God on earth. Still, others refer to the Blessed Sacrament, despite the imperfection of bread, as the True and Living Image and Presence of the Unseen God. But for non-Catholics or people of goodwill without any religion, it may be difficult to have a reference point, a reminder of the Celestial Power who also dwells on earth.

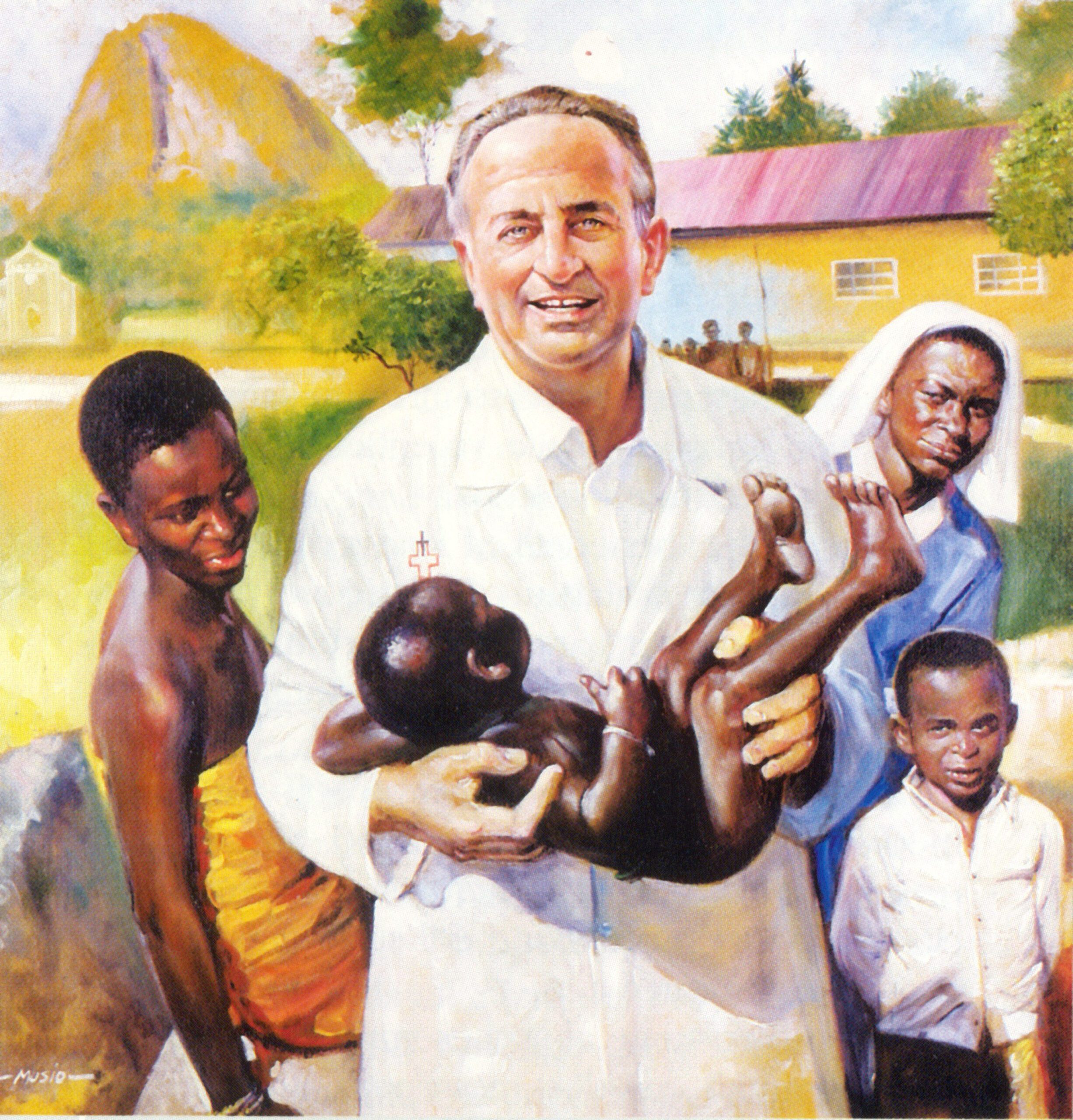

Despite the differences in belief, however, it may not be all too difficult to see God, amid the problems, suffering, and death experienced by all in this life. Victor Hugo, in Les Miserables, wrote: “To love another person is to see the face of God.” Truly, there are many human “images of God,” both recognized and unsung, around us. These are people who unconditionally love and unceasingly care for the underprivileged, the outcast, and the poor, without any desire for honor and acknowledgment. Despite their low profile and silent work, however, many cannot help but notice the efforts of these “images of God” because they literally become beacons of light and hope amid the world’s darkness and turmoil.

The latest among these beacons are this year’s co-winners of the Nobel Peace Prize, Malala Yousafzai, a 17 year-old Pakistani girl, and Mr. Kailash Satyarthi, a 60 year-old Indian child rights activist. The two represent hope in the field of women’s and children’s rights, respectively. Aside from an affirmation of their work and advocacy, their victory is a testament to how people can work together in peace to achieve a common cause, especially in a culturally and politically diverse region such as South Asia. Malala is Muslim while Kailash is Hindu.

EDUCATION HEROINE

At age 17, Malala Yousafzai is the youngest Nobel Peace laureate. A passionate child education activist, Malala was shot in the head by Taliban gunmen in October 2012 for campaigning for young Pakistani girls’ right to education in northwest Pakistan.

Malala first came under the spotlight in 2009 when she, then a seventh grader, wrote an anonymous online diary entitled “Diary of a Pakistani Schoolgirl” for the British Broadcasting Company’s (BBC’s) Urdu language website about life under the Talibans. Malala wrote that schools were closed down in the district of Swat, after the Taliban issued an edict banning girls’ education. Under a distorted interpretation of Sharia law, the militants destroyed 150 schools and blew up 5 others despite the Pakistani government’s offer of protection for education. In spite of the fear she felt and the tangible threat she experienced, she proceeded to write the diary and had counterpart articles published in a newspaper, under the pen name “Gul Makai,” decrying the militant groups’ terrorism.

Malala wrote about the days leading up to January 15, 2009, the last time the Swat girls would temporarily set foot on their beloved school. In her narratives, Malala admitted that she became very tense and nervous, even paranoid, every time she walked to and from school, after the edict was issued. Caution was also taken by school administrators and students not to attract attention to the girls, who were asked to refrain from wearing their uniforms or colorful dresses on the last few days of school. While most students wondered why their school principal did not announce the date when school would resume after the winter vacation began on January 15, Malala surmised that January 15 was the day before the Taliban’s order was to be imposed.

“The night was filled with the noise of artillery fire and I woke up three times. But since there was no school, I got up later at 10 am. Afterwards, my friend came over and we discussed our homework. Today is 15 January, the last day before the Taliban’s edict comes into effect, and my friend was discussing homework as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened,” wrote Malala on that day’s online journal entry.

Malala continued to write the diary after the closure and destruction of schools. She also openly spoke out against the Taliban in media and continued to advance the cause for women’s education. After a series of clashes between the government and the militants, the local Taliban leadership announced, on February 21, 2009, that the ban on women’s education would be lifted but only until exams culminated in March. Girls also had to wear burqas (Muslim head and face coverings). Her blog ended on March 12, 2009.

‘I AM MALALA’

The following summer, Malala rose to prominence after a documentary about her life and struggles to promote girls’ education in her province was produced and released by the New York Times. Aside from attracting the world’s attention, she also earned the ire of the Taliban, which has been terrorizing the region since 2004.

On October 9, 2012, while on her school van, a gunman who stopped their driver asked the passengers who Malala was. Thinking that the man may be a journalist, some of the girls in the van looked at Malala, revealing her identity to the man. The man then fired three bullets at Malala, one of which hit the left side of her forehead. The bullet travelled through the length of her face, before going into her shoulder. She remained unconscious and in critical condition for days, but when she improved, she was transferred to the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England, where she is now based.

Soon after her shooting, waves of outrage and support flooded for and in behalf of Malala. United Nations Special Envoy for Global Education Gordon Brown, a former U.K. Prime Minister, launched a petition using the slogan “I am Malala” to demand that all children around the world be in school by the end of 2015. Malala’s shooting also paved the way for Pakistan to ratify its first “Right to Education Bill.” In July 2013, Malala spoke at the United Nations to call for worldwide access to education.

“SAVE THE CHILDHOOD” MOVEMENT

On the other hand, sixty year-old Kailash Sharma, later known as Kailash Satyarthi, was born in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. He was trained as an electrical engineer but pursued a career in teaching after completing his post-graduate degree. In 1980, he gave up his career in the academe to pursue a child rights advocacy as secretary-general of the Bonded Labor Liberation Front. But his passion for education did not end when he stopped being a lecturer. In the same year, he founded the Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA) or “Save the Childhood Movement,” the first civil society group against child labor.

Through BBA, Kailash introduced the concept of Bal Mitra Gram (BMG), meaning child-friendly village. BMG, which he introduced in 2001, is a way of nipping child labor at its source, i.e., in the poor villages of India’s rural regions, where age-old customs, rigidity, and other barriers prevent children from growing up normally, as children should.

“We realize that we have to solve this problem right at the source. And the villages are the source of the problem of child labor. Unfortunately, 70% of child labor work force comes from villages; they live in the villages and work in an agriculture set up. So we decided to create an environment where all children are withdrawn from child labor; all children are returned to school; all children have their own voices and, finally, their voices are heard by the authorities,” Mr. Satyarthi said in an informational video about BMG.

Under BMG, activist-advocates talk to the parents of already employed children to convince them of the importance of giving an education to children. After the usually resistant parents agree to bring their children to school, the next phase is to constitute a children’s parliament or Bal Panchayat. At the children’s parliament, children elect their own representatives who will bring their concerns to the village’s own council for action. Representatives of the children’s parliament regularly attend meetings of the village assembly to raise these issues. The children’s parliament not only raises awareness of children’s rights, but provides children access, not only to village leaders, but to local authorities as well.

The members of the children’s parliament also go house-to-house to ensure that no child is forced to work or stay out of school, even to the point of helping rescue children trapped in child labor. The children’s parliament also ensures that children already enrolled in school will be retained throughout the duration of the course so that they will be able to complete it.

Other issues that BMGs are able to resolve are: girls being coerced to marry at a very early age, the absence of separate toilets for boys and girls in schools, limited access to safe drinking water, etc. Today, there are at least 275 BMGs across India, with more than a hundred on their way to becoming child-friendly villages.

“GOD WITH US”

In Luke’s account of the Annunciation of the Birth of Jesus, Isaiah’s prophecy, “Therefore, the Lord Himself will give you a sign; the young woman, pregnant and about to bear a son, shall name him Emmanuel (Is 7:14),” is fulfilled in the words of the Archangel Gabriel, “Behold, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you shall name him Jesus (Lk 1:31).”

“Emmanuel,” “God with us.” Such is the unfathomable mystery and paradox of the Incarnation – the Omnipotent God taking the form of a human, and taking the form of a lowly child at that. For sure, many, both then and now, scoffed at and mocked the doctrine of the Incarnate God, who even assumed the state of an insignificant and powerless child! Perhaps many, too, are laughing at Catholics, not only for commemorating the Birth of the God-Child on December 25, but for adoring the Sto. Niño or the Infant Jesus in all His various titles and images.

During His active ministry, however, Jesus clearly showed His love for “the little ones” and secured a rightful place for children in society: “Whoever receives this child in My name receives Me, and whoever receives Me received the One who sent Me. For the one who is least among all of you is the one who is the greatest.” (Lk 9:48).

Invoking the words of Jesus, there is no doubt that children are also images of God on earth. Their innocence, their meekness, and their poverty lead us to the contemplation of the God-Child. Treating children with respect, giving them their due, ensuring their welfare, and loving them are tantamount to receiving the Lord Jesus Himself. Indeed, to love and care for children is to see the face of God.

In the same way, those who receive and love children, as Jesus did, are also images of God. People like Malala and Kailash, who both used their God-given talents and who have the best interest of children in mind and at heart, saw innocence and goodness in the little ones, and therefore, without appealing to their own or any particular religion, saw God in them. In doing so, Malala and Kailash radiated the hope and love of a Providential Being.

During this Christmas Season (and hopefully, even after it), may we see the face of Jesus in children, as we continue to ensure and uphold their dignity, rights and well-being not just within our own families, but in society in general. In doing so, we not only receive the Infant Jesus in our hearts and homes but also become living images of God to others as well.