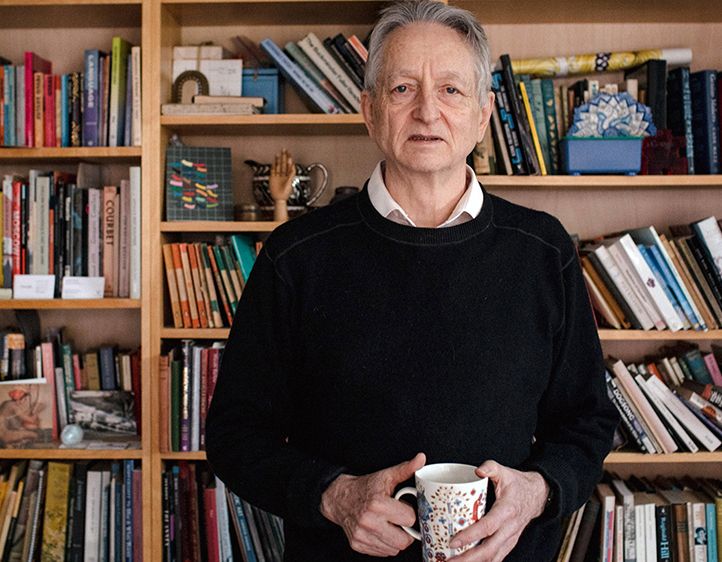

“There are a lot of people suddenly interested in AI ethics because they realize they’re playing with fire,” says Brian Green, an AI ethicist at Santa Clara University. “And this is the biggest thing since fire.”

The field of AI ethics includes two broad categories. One is the philosophical and sometimes theological questioning about how artificial intelligence changes our destiny and role as humans in the universe; the other is a set of nuts-and-bolts questions about the impact of powerful AI consumer products, like smartphones, drones, and social media algorithms.

The first is concerned with what is termed artificial general intelligence. AGI describes the kind of powerful artificial intelligence that not only simulates human reasoning but surpasses it by combining computational might with human qualities like learning from mistakes, self-doubt, and curiosity about mysteries within and without.

A popular word–singularity–has been coined to describe the moment when machines become smarter, and maybe more powerful, than humans. That moment, which would represent a clear break from traditional religious narratives about creation, has philosophical and theological implications that can make your head spin.

While we ponder AGI, artificial narrow intelligence is already here: Google Maps suggesting the road less traveled, voice-activated programs like Siri answering trivia questions, Cambridge Analytica crunching private data to help swing an election, and military drones choosing how to kill people on the ground.

The possible outcomes of artificial narrow intelligence gone awry include plenty of apocalyptic scenarios. A temperature control system, for example, could kill all humans because that would be a rational way to cool down the planet, or a network of energy-efficient computers could take over nuclear plants so it will have enough power to operate on its own.

The more programmers push their machines to make smart decisions that surprise and delight us, the more they risk triggering something unexpected and awful. “There’s a lack of awareness in Silicon Valley of moral questions, and churches and governments don’t know enough about the technology to contribute much for now,” says Tae Wan Kim, an AI ethicist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. “We’re trying to bridge that gap.”

RESOURCES INTO ETHICS

Tech companies themselves are steering more resources into ethics, and tech leaders are thinking seriously about the impact of their inventions. A recent survey of Silicon Valley parents found that many had prohibited their own children from using smartphones.

Google, seeking to reassure the public and regulators, published a list of seven principles for guiding its AI applications. It said that AI should be socially beneficial, avoid creating or reinforcing unfair bias, be built and tested for safety, be accountable to people, incorporate privacy design principles, uphold high standards of scientific excellence, and be made available to uses that accord with these principles.

The biggest headache for AI ethicists is that a global internet makes it harder to enforce any universal principle like freedom of speech. The corporations are, for the most part, in charge. That is especially true when it comes to deciding how much work we should let machines do.

UNIVERSAL BASIC INCOME

This kind of automation could create a permanently underemployed class of people, says Mr. Kim. A purely economic response to unemployment might be a universal basic income, or distribution of cash to every citizen, but Mr. Kim says AI ethicists cannot help returning to the realization that lives without purposeful activity, like a job, are usually miserable.

“Catholic social teaching is an important influence for AI ethicists because it addresses how important work is to human dignity and happiness,” he explains. “Money alone doesn’t give your life happiness and meaning,” he says. “You get so many other things out of work, like community, character development, intellectual stimulation, and dignity.” When his dad retired from his job running a noodle factory in South Korea, “he got money, but he lost community and self-respect,” says Mr. Kim.

That is a strong argument for valuing a job well done by human hands; but as long as we stick with capitalism, the capacity of robots to work fast and cheap is going to make them attractive, say AI ethicists.

“Maybe religious leaders need to work on redefining what work is,” says Mr. Kim. “Some people have proposed virtual reality work,” he says, referring to simulated jobs within computer games. “That doesn’t sound satisfying, but maybe work is not just gainful employment.”

AUTONOMOUS CARS

Now self-driving vehicles threaten to throw millions of taxi and truck drivers out of work. We are still at least a decade away from the day when self-driving cars occupy major stretches of our highways, but the automobile is so important in modern life that any change in how it works would greatly transform society.

Autonomous automobiles raise dozens of issues for AI ethicists. One such dilemma that a machine might face is if a crowded bus is in its fast-moving path. Should it change direction and try to kill fewer people? What if changing direction threatens a child? It is the kind of choice for which we know there might never be an algorithm, especially if one starts trying to calculate the relative worth of injuries.

Ethicists are also concerned that relying on AI to make life-altering decisions cedes even more influence than they already have to corporations that collect, buy, and sell private data, as well as to governments that regulate how the data can be used. In one dystopian scenario, a government could deny health care or other public benefits to people deemed to engage in “bad” behavior, based on the data recorded by social media companies and gadgets like Fitbit.

“COPYING PEOPLE”

Every artificial intelligence program is based on how a particular human views the world, says Mr. Green, the ethicist at Santa Clara. “You can imitate so many aspects of humanity,” he says, “but what quality of people are you going to copy?” “Copying people” is the aim of a separate branch of AI that simulates human connection. AI robots and pets can offer the simulation of friendship, family, therapy, and even romance.

One study found that autistic children trying to learn a language and basic social interaction responded more favorably to an AI robot than to an actual person. But the philosopher Alexis Elder argues that this constitutes a moral hazard. “The hazard involves these robots’ potential to present the appearance of friendship to a population” who cannot tell the difference between real and fake friends, she writes in the essay collection Robot Ethics 2.0: From Autonomous Cars to Artificial Intelligence. “Aristotle cautioned that deceiving others with false appearances is of the same kind as counterfeiting currency.”

AI, A NEW GOD?

AGI theorists pose their own set of questions. They debate whether tech firms and governments should develop AGI as quickly as possible to work out all the kinks or block its development in order to forestall machines’ taking over the planet. They wonder what it would be like to implant a chip in our brain that would make us 200 times smarter, immortal, or turn us into God. Might that be a human right? Some even speculate that AGI is itself a new god to be worshipped.

“Christians are facing a real crisis because our theology is based on how God made us autonomous,” says Mr. Kim, who is a Presbyterian deacon. “But now you have machines that are autonomous, too, so what is it that makes us special as humans?”

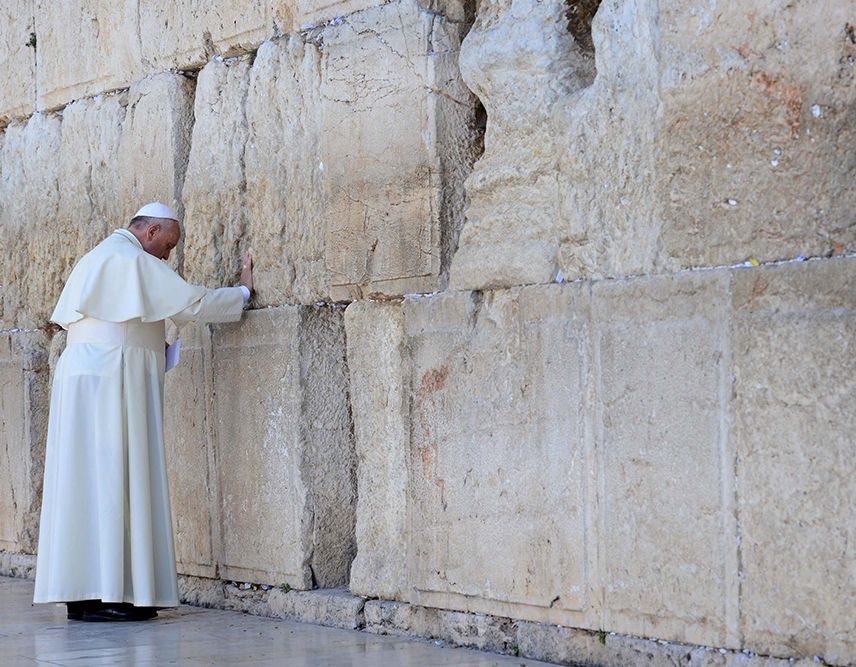

One Catholic thinker who thought deeply about the impact of artificial intelligence is Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a French Jesuit and scientist who helped to found a school of thought called transhumanism, which views all technology as an extension of the human self. “His writings anticipated the internet and what the computer could do for us,” says Ilia Delio, O.S.F., a professor at Villanova.

But his purely philosophical arguments about technology have regained currency among Catholic thinkers this century, and reading Teilhard can be a wild ride. Christian thinkers conventionally say, as St. John Paul II did, that every technological conception should advance the natural development of the human person. Teilhard went farther. He reasoned that technology, including artificial intelligence, could link all of humanity, bringing us to a point of ultimate spiritual unity through knowledge and love. He termed the moment of global spiritual coming together the Omega Point. And it was not the kind of consumer conformism that tech executives dream about.

“This state is obtained not by identification (God becoming all) but by the differentiating and communicating action of love (God all in everyone). And that is essentially orthodox and Christian,” Teilhard wrote. Published in America Magazine