The Philippines is “the cradle of Christianity in the Far East.” Even the famous global preacher Most Rev. Robert Barron himself, now Bishop of Diocese of Winona-Rochester (USA), couldn’t resist to extol the Philippine Church as the most vibrant in Catholicism, with Filipinos penetrating almost all nations on earth and filling up churches everywhere. What he said in his speech during the 51st International Eucharistic Congress in Cebu, Philippines (January 31, 2016) was awe-inspiring: “In God’s often strange providence, He will take a particular church, a particular people, and use them to invigorate and evangelize the Catholic world–YOU’RE PLAYING THAT ROLE NOW,” he told his Filipino audience.

In a nationwide survey of adults in 2014, one year before the papal visit, respondents were asked: What are the most essential characteristics of national identity or pagiging isang tunay na Pilipino in the new millennium? The majority responded by describing national identity in four ways, to wit: One, being born in the Philippines; two, being able to speak Filipino; and three, having Filipino citizenship. In addition, the majority added a fourth characteristic. They said being a Catholic, ang pagiging Katoliko, makes one a true Filipino (see Social Weather Stations, with International Social Survey Program or ISSP, February 19-23, 2014).

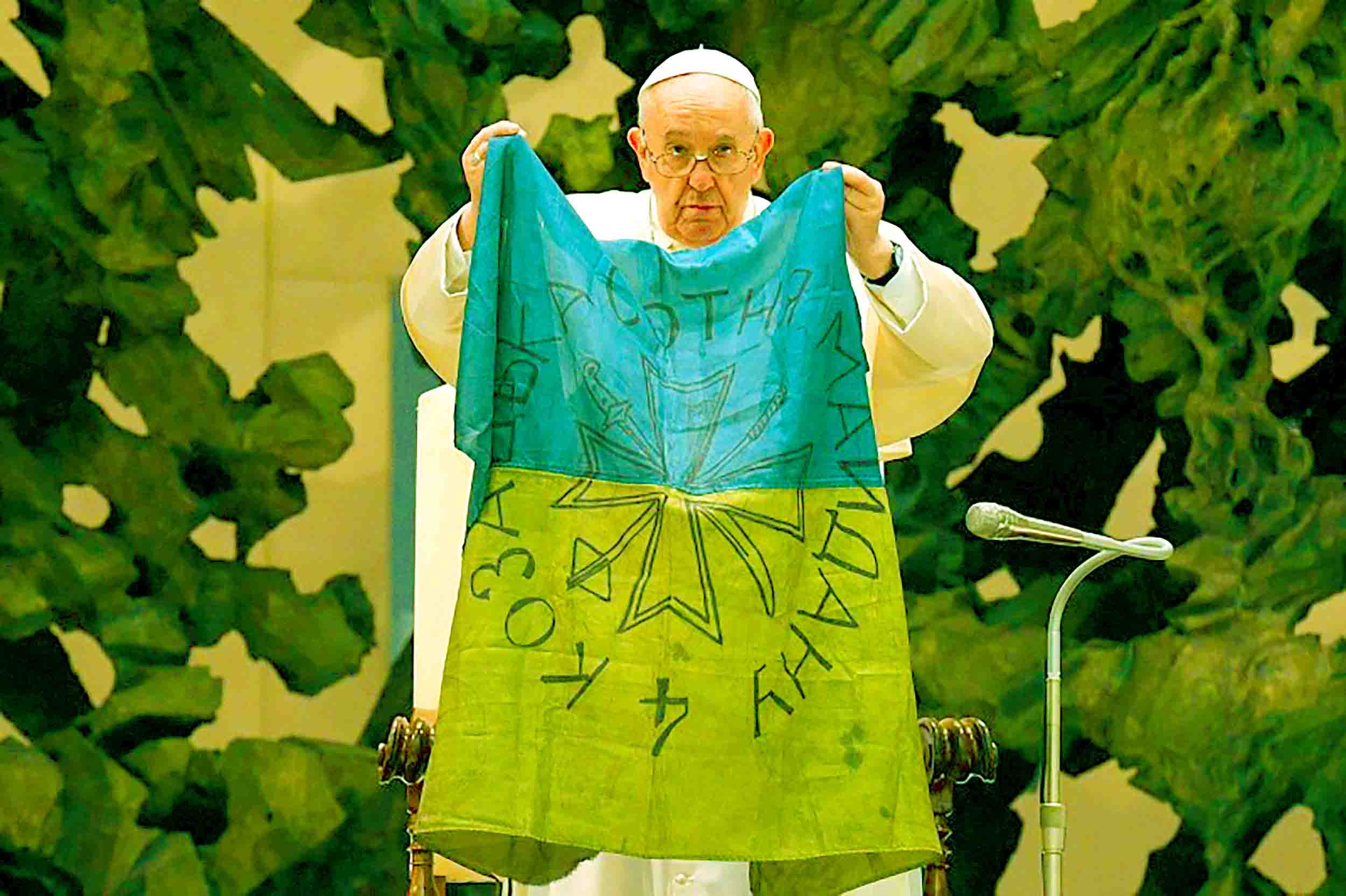

This was the kind of people Pope Francis came to see and encountered in his 2015 visit. In 2018, three years after the visit, the Holy Father identified us as “the noble Church (God’s People) in the Philippines that now stands among the great Catholic nations in the entire world.” He sent this joyful message through Cardinal Manyo Maeda, his Japanese envoy to the Manila Cathedral anniversary celebration of that year.

Long before moral corruption, cronyism, split Christianity, and born-again evangelism came to be, the Philippine archipelago was solidly populated by Catholic faithful. By 1605, forty years after the coming of the Augustinian missionaries, Catholics became the vast majority of the population and that’s a lot of good souls regularly receiving the sacraments, praying the rosary as a family, obedient to the pope and bishops, and practicing Christians in words and deeds.

In 2019, the Spanish Ambassador to the Philippines Jorge Moragas said “we cannot avoid the fact that Christianization and religion started here 500 years ago. Now the Philippines is one of the most Catholic and Christian countries in Asia and the world,” short of saying that his kababayans, the Spanish missionaries, laid the best foundation.

FIRST MISSIONARIES

Although the first mass and baptism were administered in 1521–you know the tragic story of Magellan–the year 1565 was by all reckoning the beginning of the formal evangelization of the natives. The first missionaries were the Augustinians, who survived the perilous one-time big-time journey from Mexico in November 1564.

Sea-sick and dog-tired, they reached the Philippine shores and anchored in February 1565. Hopping from one island to another, they traveled to Cebu, then to Samar-Leyte, then to Bohol. They understood the risks and dangers ahead, putting their trust in Divine Providence. Like all missionaries, the Augustinians came to blaze the trail in unknown islands where, among the indigenous people, egregious acts of violence and barbarity prevailed.

With dazzling apostolic zeal, Urdaneta and the other Augustinian friars planned, organized, and executed the obra of spreading the Gospel of Jesus in the newly colonized islands hitherto inhabited by autochthonous people, mostly Hindus, animists, Muslims, and headhunters.

After the Battle of Manila (1570-1575), Martín de Goiti, one of Legazpi’s lieutenants, appeared to have united the territorial domains of Lakan Dula of Tondo (1503-1575), Rajah Matanda (1480–1572) of Maynila, along the Pasig River, and teenager Rajah Sulayman III (1558–1575) of Sabag and Namayan. Rajah Matanda was a vassal to the Sultan of Brunei.

Think about how the missionaries worked so hard to achieve the impossible. Picture history and see with your mind’s eyes how, from the ashes of the Battle of Manila came forth a God-fearing community of Christian faithful in Manila and nearby places.

Even without a local Ordinary, the pioneering progress from 1565 to 1579 was a phenomenon short of a miracle, expressed in the written chronology of the Spanish official Antonio de Morga (1559-1636): “In these islands there is no native province or settlement which resists conversion or does not desire it” (Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, 1609).

The conversion, not proselytization, of the indigenous Filipinos to Christianity was so fast that, by the grace of God, the suffragan diocese of Manila was canonically erected on February 6, 1579 through the Papal Bull Illius Fulti Præsidio, signed by Pope Gregory XIII, the creator of the Gregorian calendar.

FRAY DOMINGO DE SALAZAR

Fray Domingo de Salazar, OP (1512-1594), a Dominican friar from the Convent of San Sebastian in Salamanca, Spain, was consecrated and installed as the first bishop (not archbishop) of Manila. The more I read history, the more I am deeply convinced there’s no panacea for the shameful underachievement of many of today’s leaders, who seem to have lost the passion and creativity to solve problems (and change the world for the better!) they once had.

From this perspective, I say that Bishop Salazar was unique. From day one, he was moving heaven and earth within the period of his actual episcopate from 1581 to 1594, that is, 13 tough years sans PLDT, Meralco, Manila Water, supermalls, Cebu-Pacific, satellite phone, smart TV, Google Search, SUV, and other convenient gadgets of the new millennium.

When he landed, he was confronted by a mammoth-size mission to accomplish with too few resources to use and a score of souls to save with too few laborers in the field.

In his 1981 visit, Pope St. John Paul II verbalized how the first hierarchical structure was set up in the Pearl of the Orient. He said: “Consider the Dominican priest Fray Domingo de Salazar. He left his native Spain and went to Venezuela, then to Mexico, stayed briefly in Florida, and finally sailed to the Philippines. Here he became the first Bishop in the Philippines–at Manila in 1578.”

Recall that the precolonial Filipinos were “a divided people… with different cultures and dialects” and more of scattered ethnological tribes hardly possessing a sense of belonging to a community broader than their kin. Since communities were tribal and were constituted by several extended families, almost surely, those who were neither family nor relatives were considered enemies. Then came the Spanish explorers and missionaries, in which evangelization went side by side with integral human development, followed by the unification process among divided tribes. The astonishing result was an inevitable movement from tribalism to an initial sense of being one people (See Archbishop Leonardo Z. Legaspi, OP, PCP II, 1991).

FOUNDERS OF TOWNS AND CITIES

The pioneer-missionaries were founders of towns and cities. The ground where they strategically built the parish church eventually became the heart of the city. When the foreign missionaries began to teach them about Christ, it marked the beginning of a Catholic nation.

From the 1600s through the 1800s, the pioneering missionaries (Augustinians, Franciscans, Dominicans, Jesuits, and Recoletos) opted to figure out and imbibe the Filipino culture, immersed themselves within different ethnological tribes, learned and talked in various Philippine dialects, and used them to touch people’s lives.

Hence, it was not surprising to hear Spanish friars speaking in Kapampangan, Ivatan, Cebuano, Ilongo, or Ilocano, almost similar to listening to the late Spanish Dominican Father Jesus Prol or Argentinian Father Luciano Felloni speaking in Tagalog.

And they did more. They founded great Catholic universities and colleges, trained and sent thousands of lay catechists to evangelize our people in the frontiers or corregimientos. They toiled to civilize the uncivilized and humanize the dehumanized, not to forget how Nick Joaquín associated the plow and the carabao with the frayles Españoles in the most pragmatic way. The combo of the plow and the carabao has revolutionized Philippine agriculture, and in the words of Joaquin in Ikon, Friar and Conquistador (2004):

“The (Spanish) friar brought the wheel and plow here, and he turned the carabao into a draft animal to pull the plow, to pull the cart. This lifted a mountain of labor off the farmer’s back and expanded his ability to produce.”

Pope St. John Paul II declared that, as early as 16th and 17th centuries, the emerging Catholic Church in the Philippines, led by the Spanish bishops and priests, was the light of Asia-Pacific and the salt of the earth (Cebu, 1981). According to David Prescott Barrows, the dedication and efforts exerted by the missionaries “softened somewhat the violence and brutality that often marred the Spanish treatment of the native, and they became the civilizing agents among the peoples whom the Spanish soldiers had conquered.”

Thanks to the Spanish missionaries who laid the cornerstone of a noble Catholic nation.