In this ‘Year of Faith’ that Pope Benedict XVI has invited us all to live and celebrate, many of us will feel the desire to ask again: What do we really believe in? A group of lay people whom I animate here in Rome, has decided that, in each of our meetings, this year, we shall take one of the articles of the Creed that we recite at Mass every Sunday and try to understand what we actually mean when we say things like ‘I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of life’ or ‘I believe in God, Father and Creator’, … or ‘I believe in one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church.’ Here, I am trying a similar effort taking just one element of our faith at a time. Always keeping in mind the whole faith of the Church, I intend to present here a simple explanation of what we usually mean when we say ‘I believe in the catholic Church. What do we really mean by saying that our Church is catholic? I will not be exhaustive, saying everything that can or must be said about it. My intention is just to help common Christians to reflect about what we believe in and to deepen the understanding of this particular element of our faith. In social contexts, where the Catholic Church is overwhelmingly present, some people just presume that words like ‘Christian’, and ‘Catholic’ just mean the same thing. Of course, they are closely related, but when I say that I am a catholic Christian, I am saying something very important about my way of living the Christian faith. And since the word ‘catholic’ is another way of saying ‘universal’ I am also declaring something about the relationship between my Christian community and other Christian communities all over the world.

Learning from history

If we open the New Testament, we will not find the expression ‘catholic Church,’ though the meaning is clearly there, in other words, as we shall explain here below. The word ‘catholic’ was added to our Creed in the first Council of Constantinople in the year 381, when the Council Fathers decided to complete the article of the Creed that spoke about the Holy Spirit, as it had been established before, in the Council of Nicea in the year 325. That is the reason why the Creed that we usually say at Mass is called the Nicene–Constantinopolitan Creed. Of course, the word ‘catholic’ had been in use in the Christian communities already for a long time. We usually like to refer to St. Ignatius, bishop of Antioch, in the Middle East, who died around the year 110, as the first Christian theologian who called the Church ‘catholic’. In his letter to the Christians of Smyrn, he wrote: “Wherever the bishop appears, there let the people be; as wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the catholic Church.” The main idea of Saint Ignatius was that the Church was similar to the Roman Empire of that time, spreading all over the world (as they knew it). So, for him, catholic meant ‘universal.’ He further explained that catholic meant that the Church was not only ‘fully present’ in the world but also ‘fully faithful’ to Christ; the faith of the Church was catholic, that is, complete and correct (orthodox).

St. Augustine, a Roman bishop in the north of Africa around the end of the fourth century, liked to say that the Church was ‘catholic’ because it ‘spoke all the languages’ of the world as it was able to welcome people from all the nations with their own particular richness. We can note here that the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC, No. 830–831) recalls this by saying that we call the Church ‘catholic, because it is ‘universal’ and also because it has in herself the ‘totality’ of the means of salvation that God offers us. Much later on, at the time of the Protestant reformation, the word ‘catholic’ took on a more juridical significance: the Catholic was the one who remained faithful to the Pope of Rome and did not follow the teachings of the Protestant reformers. One was either ‘Catholic’ or ‘Protestant.’ In recent times, specifically around the second Vatican Council, we broadened again our understanding of what being catholic means, going beyond mere geographical extension or juridical affiliation to one or the other side of the Church. In recent reflection on our catholic character, we are actually recovering and developing the beautiful vision of the Church that is already present in the New Testament and which we can find in the writings and the experience of the first generations of Christians. In our own time, we actually have come to use the word ‘catholic’ in a number of ways. Sometimes it is used to distinguish us from the Protestant Churches. But, in the Anglican communion, many communities like to call themselves with the same word. They say they are ‘Anglican Catholics.’ Other times, we use it to stress the common faith and belonging that we, ‘Roman Catholics’ share with the other catholic Eastern Churches like the Chaldean, the Syro–Malabar and Syro–Malankara, the Maronite, the Coptic, … all of them are catholic Churches in full communion with Rome. Each community follows its own tradition, specially visible in the different ways of celebrating the Eucharist, but we share the same faith and we correctly say that we are all members of the one catholic Church.

Another look at Scripture

The universal (=catholic) dimension of our religion is clearly present from the first to the last page of the Bible. Throughout the Old Testament, we can see that the people of Israel felt called by God to make His glory known to the whole world. And when the fullness of time would arrive, God would call all the nations of the world to come and adore Him in the holy city of Jerusalem. Jesus Himself probably remembered that when He said: “Is it not written: `My house shall be called a house of prayer for all the nations’? (Mk 11:17). And many times He kept surprising His own people with a public display of esteem and admiration for the faith of persons who did not belong to the people of Israel – remember the Roman centurion (Mt 8,5–10) and the Canaanite mother (Mt 15,21–28). The clearest display of the initial catholicity of the Church is probably shown to us by Luke in the second chapter of the Acts of the Apostles about how the Church herself was born. People from all known nations were gathered in the square, and the good news of the resurrection of Jesus was announced by the disciples in such a way that everyone understood it in his or her own language. And all were praising God, each in their own way. And, from that very day, the Gospel of Jesus has been preached in many languages and cultures throughout the world.

When we try to understand something important about the life and mission of the Church the best way is to look at the life and mission of her founder. What God accomplished in the world through the Church cannot be separated from the person of Christ, and He Himself can only be known, understood and served in this very concrete community of disciples that render Him visibly present in the history of the world. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (No. 830) reminds us that one of the reasons why the Church is ‘catholic’ is because Christ, the Savior of the whole universe, is present in her. When God became man, He was born to a very real family, His religion and culture are well known. We also know the place where He was born and how He suffered a human death like our own. The whole divinity of God (“all the fullness of God” – Colossians 1, 19) present in that particular limited human being called Jesus. Yet, His life did not remain locked forever in that particular culture, language, religion, … Without cancelling the concrete history of His life, God the Father raised Him to a new life through the power of the Holy Spirit, so that, after His death and resurrection Jesus can now be present and active just like God the Father and the Spirit, in all places and at all times. The Holy Spirit that transformed the dead Jesus into the Risen Lord is the same Spirit that came down upon the apostles on Pentecost Day. Ever since, wherever a group of disciples gathers in His name, His promise comes true: “where two or three are gathered in My Name, there am I in their midst” (Mt 18, 20).

Just like Jesus, a very concrete historical person, is now present and active in the world in a wonderful variety of ways, so it is with His community, the Church. Being a catholic Church means that she can express herself in an infinite variety of ways across the world, in many languages and cultures, down through the ages. It is always the same catholic Church. Think of a community of contemplative nuns who celebrate a quiet Eucharist at five in the morning, in the silence of their small monastery chapel, and then think of an African parish community that gathers on Sunday to celebrate the Eucharist in a very festive way, where hundreds of Christians sing and dance to the Lord, a feast of faith and fraternity that goes on for two or three hours. The two communities are obviously very different, but they celebrate the same Eucharist and they are the same Church. Or, again, think of a Sunday early morning Mass in Manila, and another Mass celebrated on that same Sunday in Holy Savior Church in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in the Geéz language, where the bishop presiding continuously sings in dialogue with the assembly. Each community is very different from all the others, each one is obviously only a small part of the catholic Church, yet we must say that the catholic Church is fully alive and present in every one of them.

In all cultures

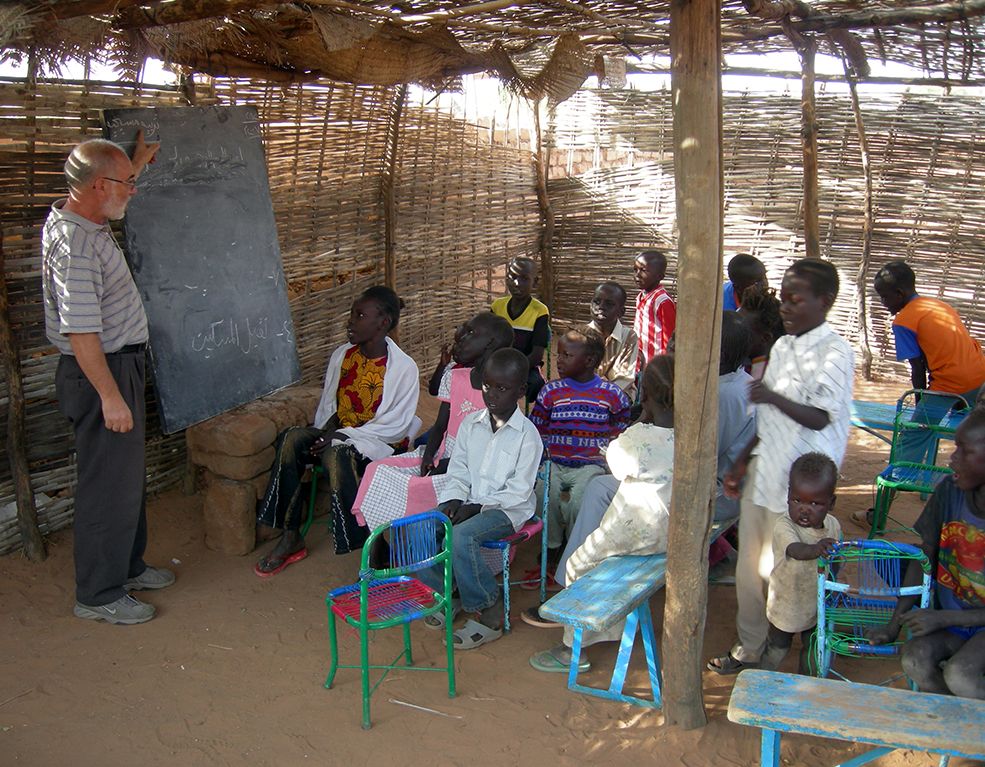

And so it is that, precisely because of her catholic character, the Church can ‘incarnate’ the Gospel of Jesus so deeply in a particular ethnic group and in their culture and particular ways of living that it may become difficult for their members to distinguish between what belongs to their faith and what to their culture. Yet, a group of missionaries eventually goes out to bring the Gospel to another people, with a different tradition, another language, very different ways of living and thinking. The Gospel is accepted and, in its own time, a very different new way of living and announcing the same Gospel of Jesus begins to take shape. Another encounter between the Gospel and a new culture will eventually produce, surprisingly, new ways of being Christian.

Two temptations may arise here, both against the true catholicity of the Church. On the one side, some people will fear losing the clear catholic identity in the middle of so many different expressions of the Church. These people will tend towards certain forms of integralism. They will be tempted to identify one particular realization of the Church in the past, and consider it as the only legitimate and correct form of life for the Church. They will think that the best way to preserve and defend the Church is to make it function like a large multinational enterprise with a strong administrative centre that continually gives detailed instructions to her subsidiary agencies throughout the world. That particular form of Church is usually very much idealised and imagined in ways that really do not correspond to the concrete reality that was there at that time. They presume that there was a time when everything in the Church was perfect and we only need to preserve it as it was. At the opposite extreme, some Christians will instead prefer to think of the Church as a loose confederation of communities linked only by the bond of Christian charity, each one going her own way. These two reactions have one thing in common: a rather unchristian fear. The first one fears losing the Christian identity in the variety of ecclesial expressions, the other fears losing the Christian freedom of the local community to discern and follow God’s will in their own local circumstances. These would be very real dangers if the catholic life of the Church were left just in our own human hands.

Fortunately, it is God Himself who looks after the Church making sure that she remains catholic and continually sends the Holy Spirit upon us to cultivate the ever–growing variety of ecclesial expressions of Christian life while, at the same time, ensuring that a truly universal communion among all grows deeper and develops at the same speed.

In this perspective, it is crucial that the Holy Spirit of God be ‘allowed’ to speak in the Church communities, both in her leaders and in her members at all levels. So long as we keep a good level of listening to each other, the Holy Spirit will surely guide the Church to become ever more catholic in ways that harmoniously combine fidelity, novelty and variety.