There may be some truth to Richard Nixon’s adage that “the Vice President can’t help you – he only can hurt you.” But Hillary Clinton is hopeful that her running mate, Jesuit-educated Tim Kaine, is a safe choice.

Nixon, who brought power to the V.P. post while serving Dwight Eisenhower for eight years, was right on his assessment. Spiro Agnew, whom he selected to be his Vice President in 1969, became more of a burden than an asset. The former governor of Maryland managed to antagonize allies (conservatives) and enemies (the press). After his reelection in 1972, Nixon trusted him with no responsibilities. He was “unfit to govern.”

Timothy Michael Kaine is not “a relatively unknown” like Spiro Agnew but concedes to being “a boring person.” He defines himself as “a man for the others” – a motto learnt from St. Ignatius of Loyola missionaries that forever changed his personal and political life.

His being a Catholic is “the key reason” why Hillary Clinton picked Tim Kaine as her running mate in the November 8 presidential elections, says Religion News Service’s editor David Gibson. It has already been the main reason why Joe Biden was Barack Obama’s pick in 2008.

“Since the 1970s, each party [Democrat and Republican] is “guaranteed about 40% of the Catholic vote”, Gibson added. “But it’s that middle 20% that is in play and, in a close election, winning that bloc is crucial” to Hillary and Donald Trump’s chances. “Now it seems almost a requirement to put a second in command who can tick the Catholic box.”

Trump – who studied for two years at Fordham University, a Jesuit school in the Bronx, before transferring to the University of Pennsylvania, “to test against the best” – is also aware of that requirement. His running mate, Indiana governor Mike Pence, “likes to call himself ‘evangelical Catholic’ even though he left the Catholicism of his birth to embrace Protestant evangelicalism while in college.”

From Harvard to Honduras

The eldest son of an ironworker and a home economics teacher, Tim Kaine was born in St Paul, Minnesota, in 1958, but grew up in the area of Kansas City, Missouri. His parents were “so devout,” Kaine told C-SPAN, that “if we got back from a vacation on a Sunday night at 7:30 p.m., they would know one church in Kansas City that had Mass that we can make it to.”

It was in Kansas that Kaine attended the all-boys Jesuit Rockhurst High School. Afterwards, he entered the University of Missouri to complete a bachelor’s degree in economics before being admitted to Harvard Law School.

At Harvard, he took a year off to volunteer with the Jesuit mission in El Progresso, Honduras. Here, he spent nine months (from 1980 to 1981) teaching carpentry and welding, and also learning Spanish.

“I came back with new lessons in humility and service, and I resolved to devote my talent and energy to helping others,” Kaine told the Democratic convention, when accepting his V.P. nomination. “My faith is my North Star for orienting my life. Since returning from Honduras 25 years ago, I have worked hard to serve my church, my family, community, city and state.”

While friends hail him as a progressive (in Richmond, the formal capital of the Confederacy, Kaine has been a staunch defender of racial equality), critics underline the omissions in the Honduras narrative.

“In the 1980s, Honduras was a crossroads of Cold War,” noted Greg Grandin, professor of Latin American History at New York University. “A year earlier, next door, Nicaragua’s Sandinistas had won their revolution. Father James Carney, a Chicago-born Jesuit priest who was executed in Honduras in 1983, recalled the moment [in his memoir]: ‘If Nicaragua won, El Salvador could win, and then Guatemala and Honduras could win.’”

At that same time, Grandin wrote in the newspaper The Nation, “CIA operatives quietly moved into the Honduran capital, Tegucigalpa, and began setting up the paramilitary network that would execute the Contra war [against the Sandinistas], that would claim 50,000 lives.”

The lessons of dictatorship

Grandin detailed a gloomy timeline: In March 1980, El Salvador’s Archbishop Oscar Romero was murdered. In January, 1981, Ronald Reagan took office as President. The ambassador he appointed to Honduras, John Negroponte, “helped cover up the activities of [death squad] Battalion 316.” On December 11, 1981 another battalion, U.S.-trained Atlacatl, “massacred upward of 900 people in the remote Salvador village of El Mozote – six of them were Jesuits.” In the meantime, “thousands of refugees, from Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua, poured into Honduras.”

“Kaine could not have avoided become immersed in those socio-religious, political currents and crosscurrents,” asserts Grandin. He would have been “exposed” to debates in the Jesuit order, where some missionaries were defending the leftist Theology of Liberation and others, like his mentor, Father Jarrel “Patrício” Wade, committed to a “more pastoral than political ethics.”

The 2009 coup

A lawyer in Richmond, Tim Kaine entered public office only in 1994 when he ran for and won the City Council. In 2005, he was elected Virginia’s governor. In the presidential campaign in 2008, he acted like a visionary endorsing not Hillary Clinton but Barack Obama (who, in the 2012 reelection bid, won the overall Catholic vote – 50% to 48%).

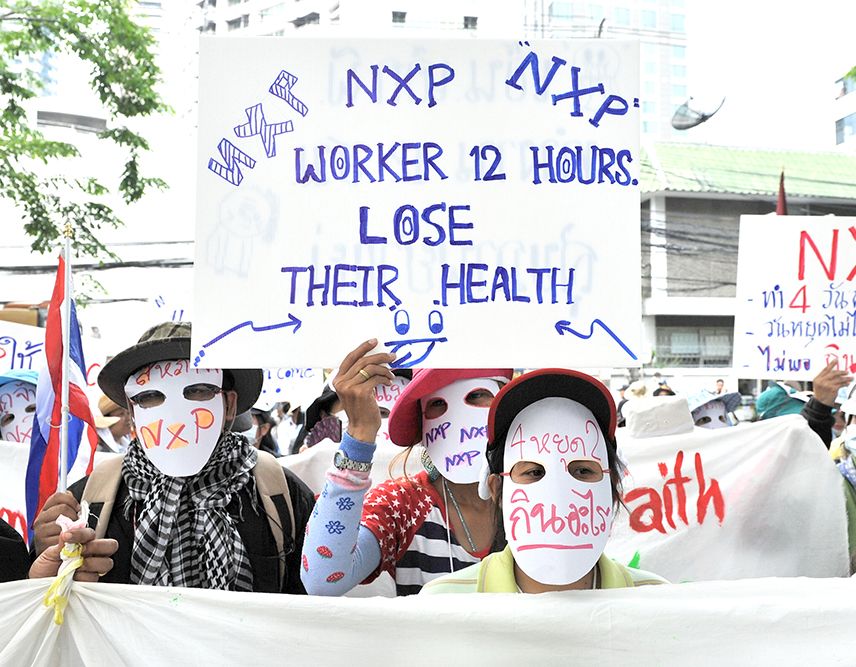

In 2009 – when a military coup in Honduras forced the elected Honduran president, Manuel Zelaya, into exile – Kaine rose to prominence to be chairman of the Democratic National Committee. In 2012, he was elected senator (joining the Armed Services, Budget, Foreign Relations and Aging Committees) – becoming the first one to deliver a speech in Spanish from the Senate floor.

While the Jesuits strongly condemned the Honduran coup, Kaine said nothing, except demanding an investigation when indigenous Lenca people leader and environmental activist Berta Cáceres was slain last March. On the contrary, he has been very active supporting deals that have led to displacement, poverty and migration, including the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA).

Death penalty and abortion

It seems like Kaine is adopting towards Honduras the same position he applies to issues such as the death penalty or abortion: “personal beliefs come second to legal and political implications.”

As a young attorney in Virginia, he used to offer legal advice free of charge to death row repentant inmates but, during his time as governor, he oversaw 11 executions. “I have a moral position against the death penalty but I took an oath of office to uphold it,” he said to The Washington Post in 2012. “Following an oath of office is also a moral obligation.”

As a heartfelt Catholic, he also opposes abortion but has maintained a “100% pro-choice voting record” in the U.S. Senate. On same sex-marriage and gay adoption, he used to align with the Church teachings but, in 2012, he turned to be a supporter: “I believe all people, regardless of sexual orientation, should be guaranteed the full rights of the legal benefits and responsibilities of marriage under the Constitution.”

Kaine might look “too much of a moderate” to some Democrats but what will attract voters, says Catholic veteran commentator E. J. Dionne, are his “working class roots and his focus on pocketbook issues like jobs, economic inequality and affordable health insurance.”

“Moreover, the issue that is far and most important to a key Catholic constituency – Hispanics [41% of the U.S. Church] – is immigration,” adds Religious News Service (RNS) editor David Gibson. “On that score, Kaine, with his long support for immigration reform and his fluency in Spanish, easily beats Trump and provides a real opportunity for the Democratic vice presidential candidate to score point for Clinton.”

Last August, RNS reported that Hillary Clinton was leading the Catholic vote, 56% to 39%, “a sizeable gap unlikely to close much by November.” And if Trump-Pence “hope to persuade swing voters in battleground states, such as Ohio and Florida, they must climb a steep mountain.”

“It’s not only Latino Catholics who are turned off by the blustery billionaire – unsurprising, given these voter’s Democratic leanings and Trump’s toxic anti-immigrant rhetoric. More intriguing (…) is the fact that many moderate and conservative Catholics also don’t seem to buy what Trump is selling.”

In 2015, Pope Francis had already given his opinion about “The Donald” when he stated: “A person who thinks only about building walls [Trump promised to erect one on the Mexican border] wherever they may be, and not building bridges, is not Christian.”

“It doesn’t take a high-priced political consultant to tell you that being on the wrong side of a widely popular pope who has captivated people far beyond the Catholic Church is a bad place to be,” said John Gehring, author of The Francis Effect: A Radical Pope’s Challenge to the American Catholic Church.